“All I see are self portraits”, the hero’s by then former wife cuttingly remarks on visiting his comeback exhibition in the company of her new husband, seemingly a much more conventional businessman. Japanese films about photographers are similar to those other countries make about writers in that their protagonists are often very flawed people, tortured artists consumed by their own trauma and often turning to drink at the expense of their personal relationships. Tadanobo Asano has in fact played similar roles a few times before. In Yoichi Higashi’s Wandering Home, he played real life war correspondent Yasuyuki Tsukahara who passed away from kidney cancer at the age of 42 after years of alcohol dependency, while in 1999’s One Step on a Mine, It’s All Over he played Taizo Ichinose whose obsession with getting a photograph of Angkor Wat eventually results in his death.

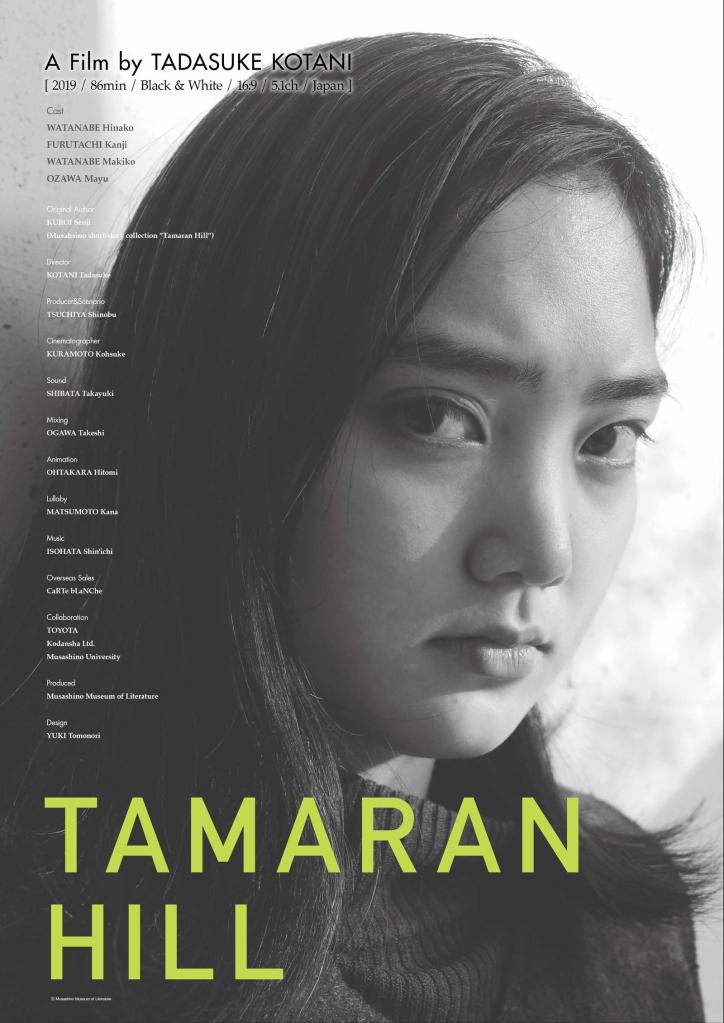

Masahisa Fukase was one of the key photographers of the post-war era and also an incredibly troubled soul. The conceit of Mark Gill’s Ravens (レイブンズ) is that Fukase is accompanied by a giant, anthropomorphised, English-speaking raven (José Luis Ferrer) who gives voice to his darkest thoughts and impulses. A magazine profile describes Fuksase’s work as having dark and occult influences, which the film attributes to the fact that his incredibly conservative father (Kanji Furutachi) used to lock him inside a more literal dark room as a punishment when he was a child.

Like many of his contemporaries, Fukase’s photographs often express the widening gap between the traditional and the modern in the changing post-war society and the film also uses many of his motifs such as his family photographs to express the changing dynamics between them. Fukase himself is caught in the nexus of this continuing battle in inheriting the legacy of his father’s war trauma. A heavy drinking, violent man, Sukezo insists that as the oldest son Fukase must take over their family photography studio and that taking photogaps is a commercial activity not an artististic one. Fukase’s wife and muse Yoko (Kumi Takiuchi) often says the same thing, undercutting Fukase’s sense of purpose in his work even while he also denies Yoko’s role as a collaborator rather than simply as a subject. “Any woman will do,” the Raven tells him though that turns out not quite to be the case.

Yoko complains that that Fukase never really looks at her but sees the world abstractedly through the lens of his camera which is really just another way of avoiding reality. She thinks she begins to understand him after belatedly meeting Fukase’s family years after their marriage and witnessing one of his father’s drunken rages first-hand, but it only seems to push them further apart. Despite his claims of artistry, Fukase quickly becomes jealous of the attention Yoko attracts as the star of his photographs as if she has eclipsed him, the artist, and can no longer be controlled by his camera. He clearly wanted the fame and acclaim through his success only seems to deepen his self-loathing and desire for death. His father had told that a man who failed to achieve success by 40 should kill himself, though when Fukase does eventually attempt to take his own life he does so by hanging, hoping that his assistant will photograph it, rather than by using the sword his father shoved at him.

Though Fukase describes Yoko as a very modern woman she too is caught by this cycle in that her mother tells her it’s a wife’s duty to forgive her husband even after he wounds with a knife during a drug-fuelled psychotic episode. Despite separating from him, Yoko continues to visit Fukase in the hospital where he remains after suffering a traumatic brain injury until his eventual death in 2012. In its way, it’s a frustrated love story in which the relationship between them is disrupted by the intrusion of outdated social codes, generational trauma, and Fukase’s own demons which appear to have been with him since childhood. The conviction that Yoko comes to is that all his pictures are actually reflections of himself and that he is incapable of seeing the world through any other lens even as he tells her that the sky is just the sky and ravens are just ravens, nothing means anything. He tells his assistant that he thought he was in search of death the whole time, but maybe it was death that was looking for him. Dreamlike and ethereal, Gill weaves back and fore throughout Fukase’s life from his conservative upbringing to the heady 1970s and gradual comedown of his later years before finally discovering a melancholy sense of serenity as Fukase, finally, dares to gaze back into the lens.

Ravens screens 20th June as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival.

International trailer (dialogue free)