Jo Shishido played his fare share of icy hitmen, but they rarely made it through such seemingly inexorable events as the hero of Takashi Nomura’s A Colt is My Passport (拳銃は俺のパスポート, Colt wa Ore no Passport). The actor, known for his boyishly chubby face puffed up with the aid of cheek implants, floated around the lower end of Nikkatsu’s A-list but by 1967 his star was on the wane even if he still had his pick of cooler than cool tough guys in Nikkatsu’s trademark action B-movies. Mixing western and film noir, A Colt is My Passport makes a virtue of Japan’s fast moving development, heartily embracing the convenience of a society built around the idea of disposability whilst accepting the need to keep one step ahead of the rubbish truck else it swallow you whole.

Jo Shishido played his fare share of icy hitmen, but they rarely made it through such seemingly inexorable events as the hero of Takashi Nomura’s A Colt is My Passport (拳銃は俺のパスポート, Colt wa Ore no Passport). The actor, known for his boyishly chubby face puffed up with the aid of cheek implants, floated around the lower end of Nikkatsu’s A-list but by 1967 his star was on the wane even if he still had his pick of cooler than cool tough guys in Nikkatsu’s trademark action B-movies. Mixing western and film noir, A Colt is My Passport makes a virtue of Japan’s fast moving development, heartily embracing the convenience of a society built around the idea of disposability whilst accepting the need to keep one step ahead of the rubbish truck else it swallow you whole.

Kamimura (Joe Shishido) and his buddy Shiozaki (Jerry Fujio) are on course to knock off a gang boss’ rival and then get the hell out of Japan. Kamimura, however, is a sarcastic wiseguy and so his strange sense of humour dictates that he off the guy while the mob boss he’s working for is sitting right next to him. This doesn’t go down well, and the guys’ planned airport escape is soon off the cards leaving them to take refuge in a yakuza safe house until the whole thing blows over. Blowing over, however, is something that seems unlikely and Kamimura is soon left with the responsibility of saving both his brother-in-arms Shiozaki, and the melancholy inn girl (Chitose Kobayashi) with a heart of gold who yearns for an escape from her dead end existence but finds only inertia and disappointment.

The young protege seems surprised when Kamimura tosses the expensive looking rifle he’s just used on a job into a suitcase which he then tosses into a car which is about to be tossed into a crusher, but Kamimura advises him that if you want to make it in this business, you’d best not become too fond of your tools. Kamimura is, however, a tool himself and only too aware how disposable he might be to the hands that have made use of him. He conducts his missions with the utmost efficiency, and when something goes wrong, he deals with that too.

Efficient as he is, there is one thing that is not disposable to Kamimura and that is Shiozaki. The younger man appears not to have much to do but Kamimura keeps him around anyway with Shiozaki trailing around after him respectfully. More liability than anything else, Kamimura frequently knocks Shiozaki out to keep him out of trouble – especially as he can see Shiozaki might be tempted to leap into the fray on his behalf. Kamimura has no time for feeling, no taste for factoring attachment into his carefully constructed plans, but where Shiozaki is concerned, sentimentality wins the day.

Mina, a melancholy maid at a dockside inn, marvels at the degree of Kamimura’s devotion, wishing that she too could have the kind of friendship these men have with each other. A runaway from the sea, Mina has been trapped on the docks all her adult life. Like many a Nikkatsu heroine, love was her path to escape but an encounter with a shady gangster who continues to haunt her life put paid to that. The boats come and go but Mina stays on shore. Kamimura might be her ticket out but he wastes no time disillusioning her about his lack of interest in becoming her saviour (even if he’s not ungrateful for her assistance and also realises she’s quite an asset in his quest to ensure the survival of his ally).

Pure hardboiled, A Colt is My Passport is a crime story which rejects the femme fatal in favour of the intense relationship between its two protagonists whose friendship transcends brotherhood but never disrupts the methodical poise of the always prepared Kamimura. The minor distraction of a fly in the mud perhaps reminds him of his mortality, his smallness, the fact that he is essentially “disposable” and will one day become a mere vessel for this tiny, quite irritating creature but if he has a moment of introspection it is short lived. The world may be crunching at his heels, but Kamimura keeps moving. He has his plan, audacious as it is. He will save his buddy, and perhaps he doesn’t care too much if he survives or not, but he will not go down easy and if the world wants a bite out of him, it will have to be fast or lucky.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

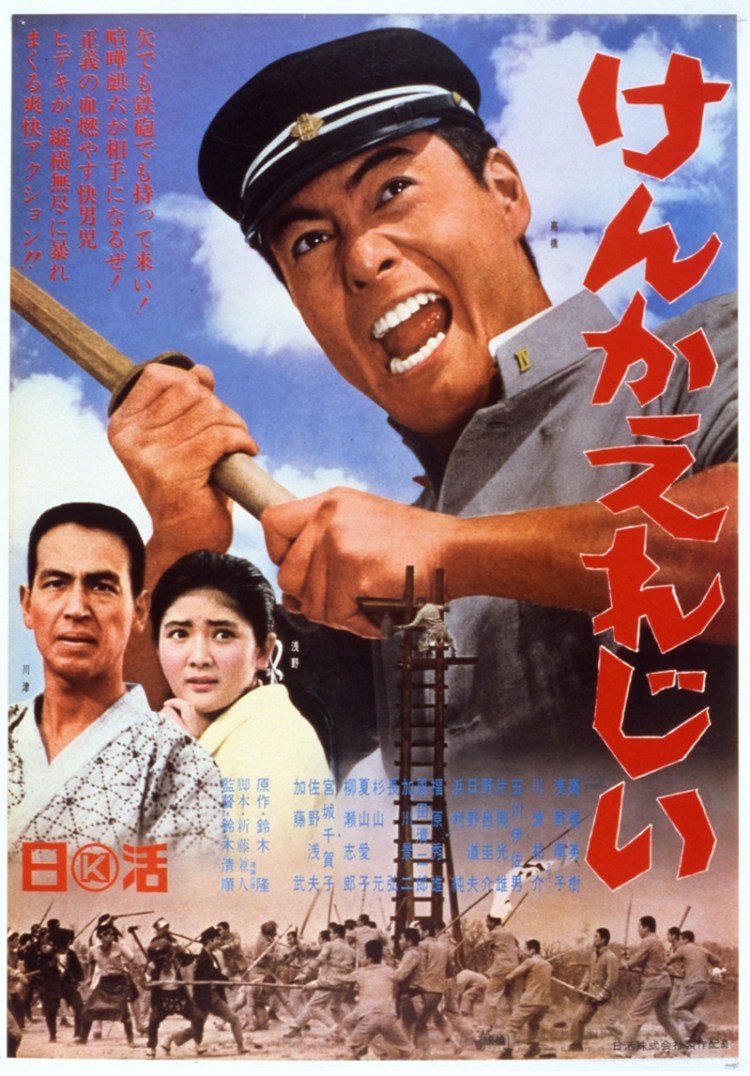

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self.

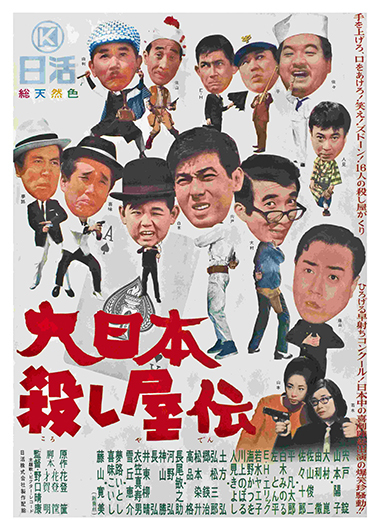

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self. “If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot. Where there’s danger, there’s money! Or, maybe just danger, who knows but whatever it is, it certainly doesn’t lack for excitement. Ko Nakahira is best known for his first feature, Crazed Fruit, the youthful romantic drama ending in speed boat murder which ushered in the Sun Tribe era. Though he later tried to make a return to more artistic efforts, it’s Nakahira’s freewheeling Nikkatsu crime movies that have continued to capture the hearts of audience members. Danger Pays (AKA Danger Paws, 危いことなら銭になる, Yabai Koto Nara Zeni ni Naru) is among the best of them with its cartoon-like, absurd crime caper world filled with bumbling crooks and ridiculous setups.

Where there’s danger, there’s money! Or, maybe just danger, who knows but whatever it is, it certainly doesn’t lack for excitement. Ko Nakahira is best known for his first feature, Crazed Fruit, the youthful romantic drama ending in speed boat murder which ushered in the Sun Tribe era. Though he later tried to make a return to more artistic efforts, it’s Nakahira’s freewheeling Nikkatsu crime movies that have continued to capture the hearts of audience members. Danger Pays (AKA Danger Paws, 危いことなら銭になる, Yabai Koto Nara Zeni ni Naru) is among the best of them with its cartoon-like, absurd crime caper world filled with bumbling crooks and ridiculous setups. The bright and shining post-war world – it’s a grand place to be young and fancy free! Or so movies like Tokyo Mighty Guy (東京の暴れん坊, Tokyo no Abarembo) would have you believe. Casting one of Nikkatsu’s tentpole stars, Akira Kobayshi, in the lead, Buichi Saito’s Tokyo Mighty Guy is, like previous Kobayashi/Saito collaboration

The bright and shining post-war world – it’s a grand place to be young and fancy free! Or so movies like Tokyo Mighty Guy (東京の暴れん坊, Tokyo no Abarembo) would have you believe. Casting one of Nikkatsu’s tentpole stars, Akira Kobayshi, in the lead, Buichi Saito’s Tokyo Mighty Guy is, like previous Kobayashi/Saito collaboration  What are you supposed to do when you’ve lost a war? Your former enemies all around you, refusing to help no matter what they say and there are only black-marketers and gangsters where there used to be merchants and craftsmen. Everyone is looking out for themselves, everyone is in the gutter. How are you supposed to build anything out of this chaos? Perhaps you aren’t, but you have to go one living, somehow. The picture of the immediate post-war world which Suzuki paints in Gate of Flesh (肉体の門, Nikutai no Mon) is fairly hellish – crowded, smelly marketplaces thronging with desperate people. Based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura (who also provided the source material for Suzuki’s Story of a Prostitute), Gate of Flesh has its lens firmly pointed at the bottom of the heap and resolutely refuses to avert its gaze.

What are you supposed to do when you’ve lost a war? Your former enemies all around you, refusing to help no matter what they say and there are only black-marketers and gangsters where there used to be merchants and craftsmen. Everyone is looking out for themselves, everyone is in the gutter. How are you supposed to build anything out of this chaos? Perhaps you aren’t, but you have to go one living, somehow. The picture of the immediate post-war world which Suzuki paints in Gate of Flesh (肉体の門, Nikutai no Mon) is fairly hellish – crowded, smelly marketplaces thronging with desperate people. Based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura (who also provided the source material for Suzuki’s Story of a Prostitute), Gate of Flesh has its lens firmly pointed at the bottom of the heap and resolutely refuses to avert its gaze.