“Isn’t this style called surrealism?” a little girl asks, watching a WWII GI giving John Ford’s Monument Valley a post-modern makeover depicting John Lennon and a Martian in preparation for a live concert by hip girlband ZELDA. Arriving at the beginning of the Bubble era, Naoto Yamakawa’s 35mm commercial feature debut The New Morning of Billy the Kid (ビリィ★ザ★キッドの新しい夜明け, Billy the Kid no Atarashii Yoake) was the first film to be produced by the entertainment arm of department store chain Parco (along with record label Vap) which also distributed and draws inspiration from several stories by genre pioneer Genichiro Takahashi who at one point appears on screen proclaiming singer-songwriter Miyuki Nakajima, a version of whom appears as a character, as one of the three greatest Japanese poets of the age. What transpires is largely surreal, but also a kind of post-modern allegory in which the world is beset by the “anxiety and destruction” of salaryman society.

Yamakawa opens in black and white and in Monument Valley in which only the figure of a young man in a cowboy outfit is in vivid colour while a voiceover from the American President warns that a savage band of gangsters is currently holding the world to ransom. Yet “Monument Valley” turns out to be only an image filling the wall of Bar Slaughterhouse, the cowboy, Billy the Kid (Hiroshi Mikami) stepping out of the painting having lost his horse and apparently in search of a job. The barman (Renji Ishibashi) is reluctant to give him one, after all he has six bodyguards already ranging from the legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi to an anthropomorphism of Directory Enquiries, 104 (LaSalle Ishii). Nevertheless, after threatening to leave (through the front door) Billy asks for a job as a waiter instead in return for food and board while collecting the bounty for any gangsters he kills in the course of his duties.

The bar is in some senses an imaginary place, or at least a space of the imagination, the sanctuary of “construction and creation” where half-remembered pop culture references mingle freely. In that sense it stands in direct opposition to the salaryman reality of Bubble-era Japan where everyone works all the time and the only interests which matter are corporate. Billy takes a liking to a young office lady, “Charlotte Rampling” (Kimie Shingyoji), who complains that she’s overcome with a sense of anxiety in the crushing sameness of her life, often woken by the sound of herself grinding her teeth that is when she’s not too tired to fall asleep. The “gangsters” which eventually crash in (literally) are businessmen and authority figures, one revealing as he raids the till that he’s a dissatisfied civil servant who determined that in order to become the best of the salarymen you need an “interesting” hobby so his is being in a gang. Another later gives a speech remarking again on this sense of inner anxiety that in their soulless desk jobs they’re moving further and further away from this world of “creation and construction”, and that the sacrifice of their individuality has provoked the kind of violent madness which enables this nihilistic “terrorist” enforcement of the corporatist society against which Miyuki (Shigeru Muroi), another of the bodyguards dressed as a retro 50s-style roller diner waitress, rebels through her poetry.

Envisioned as a single set drama (save the bookending Monument Valley scenes apparently filmed on location in Arizona) Yamanaka’s drama is infinitely meta, in part a minor parody of Seven Samurai featuring a Miyamoto Musashi inspired by Kurosawa’s Kyuzo who was himself inspired by Miyamoto Musashi as the seven pop culture bodyguards stand guard over a saloon-style cafe bar beset by the forces of “order” turned modern-day bandits intent on crushing the artistic spirit in order to facilitate the rise of a boring salaryman corporate drone society. Yet for all of its absurdist humour, Harry Callahan (Yoshio Harada) telling a strange story about being a race horse, there is something quietly moving in Yamakawa’s ethereal transitions, the camera gently pulling back as a little girl who wanted to travel is suddenly surrounded by snow or the face of anxious young office lady fading into that of a prairie woman telling a bizarre tale of her life with a venomous snake. Equally a vehicle for girlband ZELDA whose music recurs throughout, the first stage number a hippyish affair set in a summer garden and the second an emo goth aesthetic more suited to what’s about to happen, Yamakawa’s zeitgeisty, post-modern drama is an advocation for the importance of the creative spirit if in another meta touch itself a rebellion against the corporate and consumerist emptiness of Bubble-era Japan.

The New Morning of Billy the Kid streams worldwide 3rd to 5th December with newly prepared English subtitles alongside two of Yamakawa’s earlier shorts courtesy of Matchbox Cine.

Original trailer (English subtitles available via CC button)

Miyuki Nakajima’s debut single, Azami-jo no Lullaby (1975)

ZELDA’s Ogon no Jikan

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired  Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era. You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals.

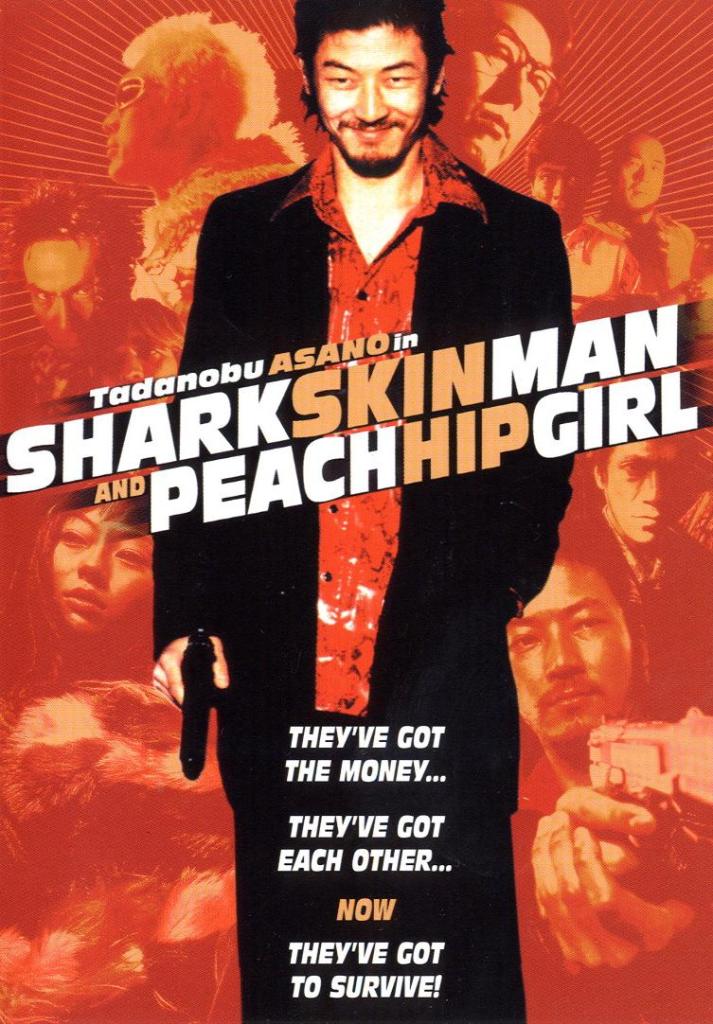

You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals. If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back.

If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back.