It’s a strange thing to say, but no two people can ever know the same person in the same way. We’re all, in a sense, in between each other, only holding some of the pieces in the puzzle of other people’s lives. Lee Dong-eun’s debut feature, In Between Seasons (환절기, Hwanjeolgi), is the story of three people who love each other deeply but find that love tested by secrets, resentments, cultural taboos and a kind of unwilling selfishness.

It’s a strange thing to say, but no two people can ever know the same person in the same way. We’re all, in a sense, in between each other, only holding some of the pieces in the puzzle of other people’s lives. Lee Dong-eun’s debut feature, In Between Seasons (환절기, Hwanjeolgi), is the story of three people who love each other deeply but find that love tested by secrets, resentments, cultural taboos and a kind of unwilling selfishness.

Beginning at the mid-point with a violent car crash, Lee then flashes back four years perviously as Soo-hyun (Ji Yun-ho) introduces his new friend, Yong-joon (Lee Won-gun), to his mother, Mi-keyong (Bae Jong-ok). Soo-hyun’s father has been living abroad in the Philippines for some time and so it’s just the two of them, while Yong-joon’s uneasy sadness is easily explained away on learning that his mother recently committed suicide. Thankful that her son has finally made a friend and feeling sorry for Yong-joon, Mi-kyeong practically adopts him, welcoming him into their home where he becomes a more or less permanent fixture until the boys leave high school.

Four years later, Soo-hyun and Yong-joon are both involved in the car crash which opened the film. Yong-joon has only minor injuries, but Soo-hyun is in a deep coma with possibly irreversible brain damage. It’s at this point that Mi-kyeong finally realises the true nature of the relationship between her son and his friend – that they had been close, inseparable lovers, and that she had never known about it.

When Mi-kyeong receives the phone call to tell her that her son has been in an accident, her friends are joking about their own terrible boys. As one puts it, there are three things a son should never tell his mother – the first being that he’s going to become a monk, the second that he’s going to buy a motorcycle, and the third is something so terrible they can’t even say it out loud. Mi-kyeong’s reaction to discovering her son is gay is predictably negative. Despite having cared for Yong-joon as a mother all these years, she can no longer bear to look at him and tells him on no uncertain terms not come visiting again. Yet for all that her reaction is only half informed by prevailing cultural norms, it’s not so much shame or disgust that she feels as resentment. Here is a man who loves her son, only differently than she does, and therefore knows things about him she never will or could hope to. She is forced to realise that the image she had of Soo-hyun is largely self created and the realisation leaves her feeling betrayed, let down, and rejected.

Both Mi-kyeong and Yong-joon ask the question “What have I done wrong?” at several points in the film – Yong-joon most notably when he’s rejected by Mi-kyeong without explanation, and Mi-kyeong when she’s considering why she’s not been included in the wedding plans for a friend’s daughter. Both Mi-kyeong and Yong-joon are made to feel excluded because they make people “uncomfortable” – Yong-joon because of his sexuality (which he continues to keep secret from his colleagues at work), and Mi-kyeong because of her grief-stricken purgatory. No one quite knows what to say to her, or wants to think about the pain and suffering she must be experiencing. They may claim they don’t want to upset her with something as joyous as a wedding but really it’s more that they don’t want her sadness to cast a shadow over the occasion.

Gradually the ice begins to thaw as Mi-kyeong allows Yong-joon back into her life again even if she can’t quite come to terms with his feelings for her son, describing him as a “friend” and embarrassed by his presence in front of her sister and other visitors. Soo-hyun’s illness and subsequent dependency ironically enough push Mi-kyeong towards the kind of independence she had always rejected – finally learning to drive, sorting out her difficult marital circumstances, and starting to live for herself as well as for her son. Yong-joon remains stubborn and in love, refusing to be shut out of Soo-hyun’s life even whilst considering the best way to live his own. Beautifully composed in all senses of the word, Lee’s frames are filled with anxious longing and inexpressible sadness tempered with occasional joy. Too astute to opt for a crowd pleasing victory, Lee ends on a more realistic note of hopeful ambiguity with anxiety seemingly exorcised and replaced with tranquil, easy sleep.

Screened at the London Korean Film Festival 2017. In Between Seasons will also be screened at the Broadway Cinema in Nottingham on 11th November.

Trailer/behind the scenes EPK (no subtitles)

Interview with director Lee Dong-eun conducted during the film’s screening at the Busan International Film Festival in 2016.

Some situations are destined to end in tears. Kaze Shindo’s Love Juice adopts the popular theme of unrequited love but complicates it with the peculiar circumstances of Tokyo at the turn of the century which requires two young women to be not just housemates but bedmates and workmates too. One is straight, one is gay and in love with her friend who seems to get off on manipulating her emotions and is overly dependent on her more responsible approach to life, but both are trapped in a low rent world of grungy nightclubs and sleazy hostess bars.

Some situations are destined to end in tears. Kaze Shindo’s Love Juice adopts the popular theme of unrequited love but complicates it with the peculiar circumstances of Tokyo at the turn of the century which requires two young women to be not just housemates but bedmates and workmates too. One is straight, one is gay and in love with her friend who seems to get off on manipulating her emotions and is overly dependent on her more responsible approach to life, but both are trapped in a low rent world of grungy nightclubs and sleazy hostess bars. In

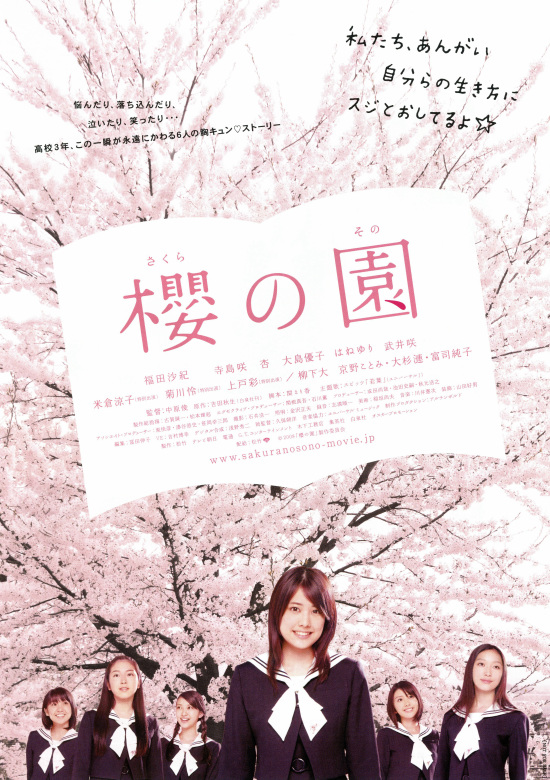

In  Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era.

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era. Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

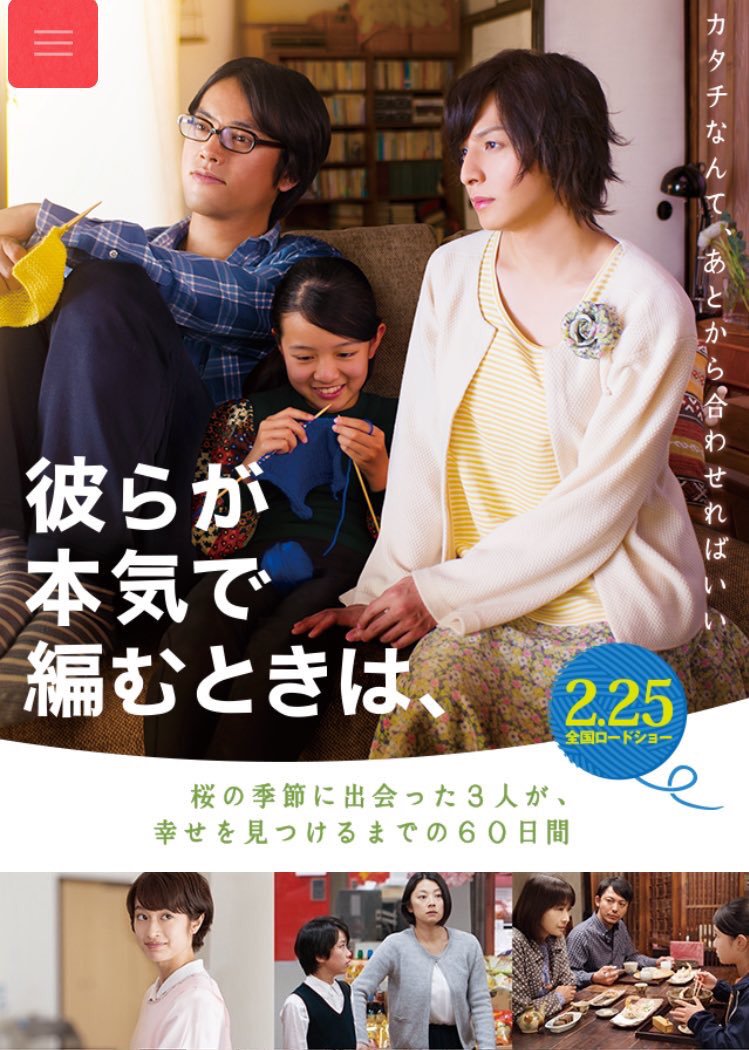

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering.

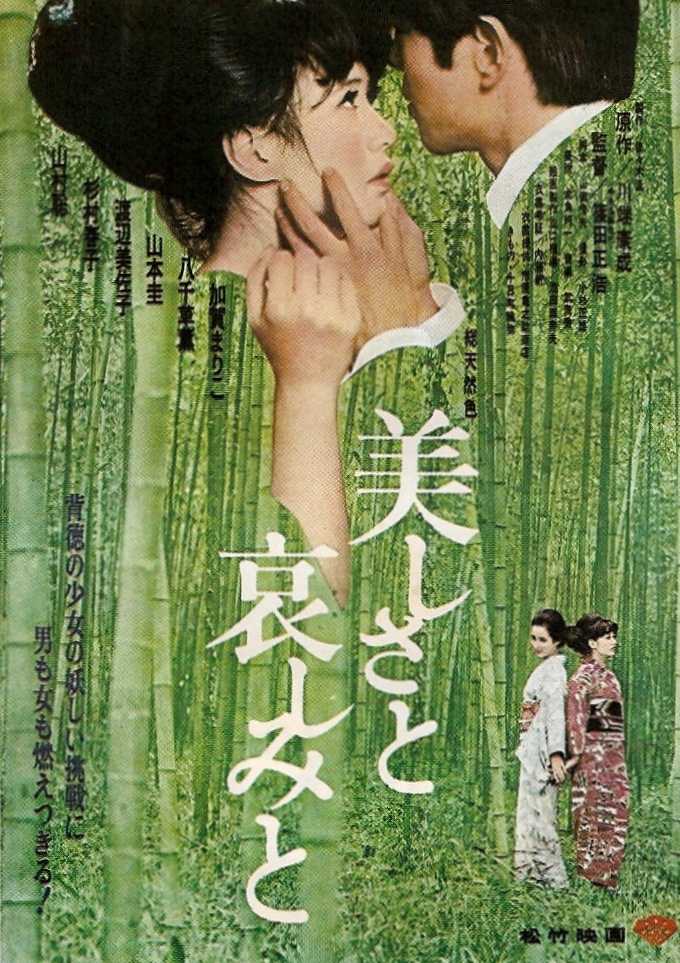

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering. Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession.

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession.

Following the surreal horror film

Following the surreal horror film  This area has a weird magnetic field, claims one of the central characters in Takuro Nakamura’s West North West (西北西, Seihokusei), it’ll throw you off course. Barriers to love both cultural and psychological present themselves with almost gleeful melancholy in this indie exploration of directionless youth in modern day Tokyo. Three young women wrestle with themselves and each other in a complex cycle of interconnected anxieties as they attempt to carve out their own paths, each somehow aware of the shape their lives should take yet afraid to pursue it. The Tokyo of West North West is one defined by disconnection, loneliness and permanent anxiety but it is not the city which is the enemy of happiness but an internal unwillingness to find release from self imposed imprisonment.

This area has a weird magnetic field, claims one of the central characters in Takuro Nakamura’s West North West (西北西, Seihokusei), it’ll throw you off course. Barriers to love both cultural and psychological present themselves with almost gleeful melancholy in this indie exploration of directionless youth in modern day Tokyo. Three young women wrestle with themselves and each other in a complex cycle of interconnected anxieties as they attempt to carve out their own paths, each somehow aware of the shape their lives should take yet afraid to pursue it. The Tokyo of West North West is one defined by disconnection, loneliness and permanent anxiety but it is not the city which is the enemy of happiness but an internal unwillingness to find release from self imposed imprisonment.