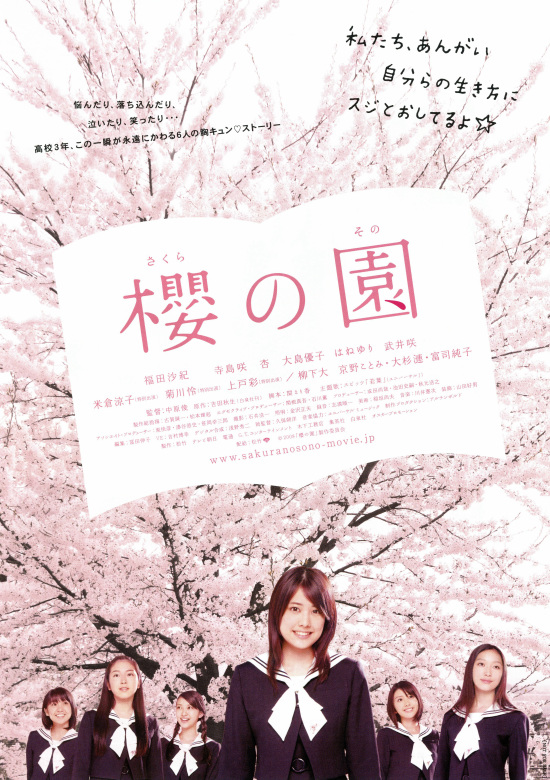

In 1990, Shun Nakahara adapted Akimi Yoshida’s manga Sakura no Sono and created a perfectly observed capsule of late ‘80s teenage life at an elite girls school where the encroaching future is both terrifying and oddly exciting. Revisiting the same material 28 years later, one can’t help feeling that the times have rolled back rather than forwards. Starring a collection of appropriately aged teenage starlets The Cherry Orchard: Blossoming (櫻の園 -さくらのその- Sakura no Sono), dispenses with the arty overtones for a far more straightforward tale of melancholy schoolgirls finding release in art but, crucially, only to a point.

In 1990, Shun Nakahara adapted Akimi Yoshida’s manga Sakura no Sono and created a perfectly observed capsule of late ‘80s teenage life at an elite girls school where the encroaching future is both terrifying and oddly exciting. Revisiting the same material 28 years later, one can’t help feeling that the times have rolled back rather than forwards. Starring a collection of appropriately aged teenage starlets The Cherry Orchard: Blossoming (櫻の園 -さくらのその- Sakura no Sono), dispenses with the arty overtones for a far more straightforward tale of melancholy schoolgirls finding release in art but, crucially, only to a point.

Less an attempt to remake the original, Blossoming acts as an odd kind of sequel in which the leading lady, Momo (Saki Fukuda), becomes fed up with her rigid life at a music conservatoire and rebelliously storms out. Already in her last year of high school, Momo is lucky enough to get a transfer to Oka Academy solely because her mother and (much) older sister are old girls. However, transfer students are rare at Oka and the other girls aren’t exactly happy to see her – they worked hard to get here but she’s just waltzed straight in without any kind of effort at all.

Gradually the situation improves. Wandering around the old school building (a European style country house) which was the setting for the first film and has now been replaced with a modern, purpose built high school complex, Momo finds the script for The Cherry Orchard and becomes fixated on the idea of putting the play on with some of the other students. However, though The Cherry Orchard used to be an annual fixture it hasn’t been performed in 11 years after being abruptly cancelled when one of the stars disgraced the school by falling pregnant.

Whereas Nakahara’s 1990 Cherry Orchard was a tightly controlled affair, penning the girls inside the school and staying with them through several crises across the two hours before their big performance, Blossoming has no such conceits and adopts a formula much more like the classic sports movie as the underdog girls fight to put the play on and then undergo physical training (complete with montages) rather than rehearsals.

Momo’s rebellion is (in a sense) a positive one as she abandons something she was beginning to find no longer worked for her to look for something else and also gains a need to see things through rather than give up when times get hard. The drama of the 1990 version is kickstarted when a student is caught smoking in a cafe with delinquents from another school, aside from being told that students are expected to go straight home, Momo feels little danger in hanging out in an underground bar where her music school friend plays in a avant-garde pop band.

Though this reflects a change in eras it also points to a slight sanitisation of the source material. Gone are the illicit boyfriends (though there is one we don’t see) and barely repressed crushes, these teens are still in the land of shojo – dreaming of romance but innocently. Teenage pregnancy becomes a recurrent theme but lost opportunities hover in the background as the girls are seen from their own perspective rather than the wistful melancholy of those looking back on their youth.

Such commentary is left to the “old girls” represented by Momo’s soon to be married sister and the girls’ teacher, each of whom is still left hanging thanks to the cancellation of the play during their high school years. Despite her impending marriage, Momo’s sister does not seem to be able to put the past behind her and may be nursing a long term unrequited crush on a high school classmate. Blossoming echoes some of the concerns of Cherry Orchard, notably in its central pairing as lanky high jumper Aoi (Anne Watanabe) worries over a perceived lack of femininity while the more refined Mayuko (Saki Terashima) silently pines for her, unable to make her feelings plain. The 1990 version presented a painful triangle of possibly unrequited loves and general romantic confusion but it did at least allow a space for overt discussion rather than the half hearted subtly of a mainstream idol film in a supposedly more progressive era.

Nevertheless, Nakahara’s second pass at teenage drama does fulfil on the plucky high school girls promise as the gang get together to put the show on right here. Much less nuanced than the earlier version, Blossoming’s teens are just as real even if somehow more naive than their ‘80s counterparts. Team building, friendship, and perseverance are the name of the day as the passing of time takes a back seat, relegated to Momo’s sad smile as she alone witnesses the painful love drama of her melancholy friend.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era.

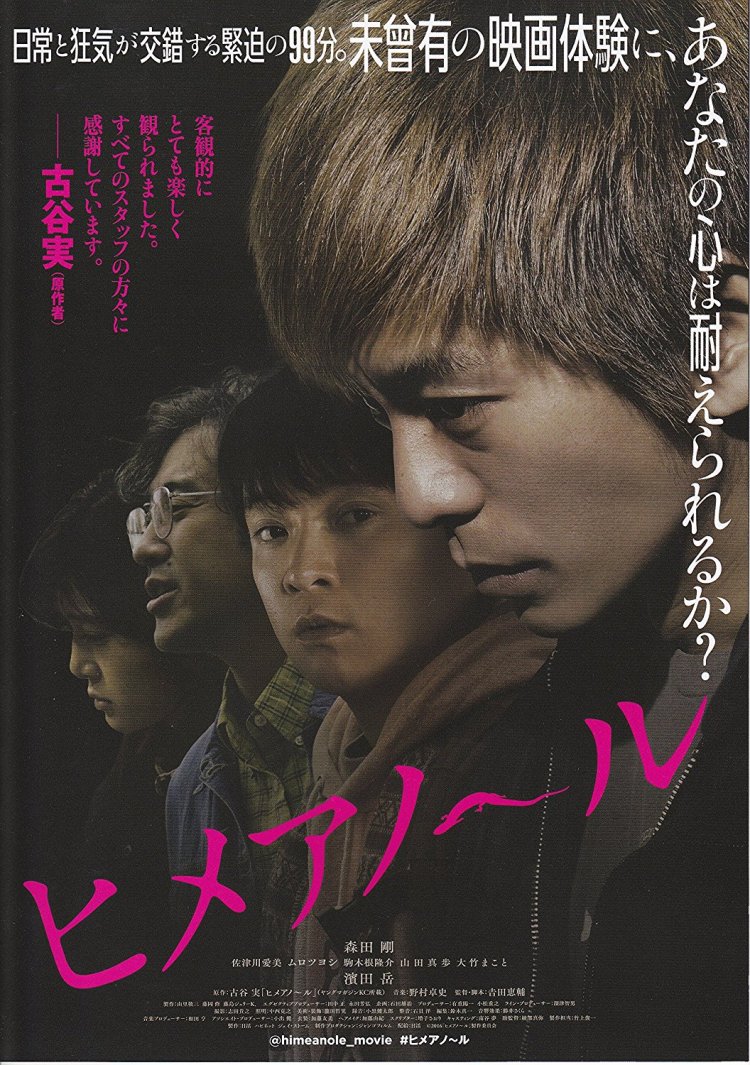

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era. Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill.

Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill.

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,  Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again.

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again. The world of shojo manga is a particular one. Aimed squarely at younger teenage girls, the genre focuses heavily on idealised, aspirational romance as the usually female protagonist finds innocent love with a charming if sometimes shy or diffident suitor. Then again, sometimes that all feels a little dull meaning there is always space to send the drama into strange or uncomfortable areas. Policeman and Me (PとJK, P to JK), adapted from the shojo manga by Maki Miyoshi is just one of these slightly problematic romances in which a high school girl ends up married to a 26 year old policeman who somehow thinks having an official certificate will make all of this seem less ill-advised than it perhaps is.

The world of shojo manga is a particular one. Aimed squarely at younger teenage girls, the genre focuses heavily on idealised, aspirational romance as the usually female protagonist finds innocent love with a charming if sometimes shy or diffident suitor. Then again, sometimes that all feels a little dull meaning there is always space to send the drama into strange or uncomfortable areas. Policeman and Me (PとJK, P to JK), adapted from the shojo manga by Maki Miyoshi is just one of these slightly problematic romances in which a high school girl ends up married to a 26 year old policeman who somehow thinks having an official certificate will make all of this seem less ill-advised than it perhaps is. Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as

Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as  Picking up on the well entrenched penny dreadful trope of the tragic flower seller the Shoujo Tsubaki or “Camellia Girl” became a stock character in the early Showa era rival of the Kamishibai street theatre movement. Like her European equivalent, the Shoujo Tsubaki was typically a lower class innocent who finds herself first thrown into the degrading profession of selling flowers on the street and then cast down even further by being sold to a travelling freakshow revue. This particular version of the story is best known thanks to the infamous 1984 ero-guro manga by Suehiro Maruo, Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show. Very definitely living up to its name, Maruo’s manga is beautifully drawn evocation of its 1930s counterculture genesis – something which the creator of the book’s anime adaptation took to heart when screening his indie animation. Midori, an indie animation project by Hiroshi Harada, was screened only as part of a wider avant-garde event encompassing a freak show circus and cabaret revue worthy of any ‘30s underground scene.

Picking up on the well entrenched penny dreadful trope of the tragic flower seller the Shoujo Tsubaki or “Camellia Girl” became a stock character in the early Showa era rival of the Kamishibai street theatre movement. Like her European equivalent, the Shoujo Tsubaki was typically a lower class innocent who finds herself first thrown into the degrading profession of selling flowers on the street and then cast down even further by being sold to a travelling freakshow revue. This particular version of the story is best known thanks to the infamous 1984 ero-guro manga by Suehiro Maruo, Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show. Very definitely living up to its name, Maruo’s manga is beautifully drawn evocation of its 1930s counterculture genesis – something which the creator of the book’s anime adaptation took to heart when screening his indie animation. Midori, an indie animation project by Hiroshi Harada, was screened only as part of a wider avant-garde event encompassing a freak show circus and cabaret revue worthy of any ‘30s underground scene.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness. Tradition vs modernity is not so much of theme in Japanese cinema as an ever present trope. The characters at the centre of Yukiko Mishima’s adaptation of Aoi Ikebe’s manga, A Stitch of Life (繕い裁つ人, Tsukuroi Tatsu Hito), might as well be frozen in amber, so determined are they to continuing living in the same old way despite whatever personal need for change they may be feeling. The arrival of an unexpected visitor from what might as well be the future begins to loosen some of the perfectly executed stitches which have kept the heroine’s heart constrained all this time but this is less a romance than a gentle blossoming as love of craftsmanship comes to the fore and an artist begins to realise that moving forward does not necessarily entail a betrayal of the past.

Tradition vs modernity is not so much of theme in Japanese cinema as an ever present trope. The characters at the centre of Yukiko Mishima’s adaptation of Aoi Ikebe’s manga, A Stitch of Life (繕い裁つ人, Tsukuroi Tatsu Hito), might as well be frozen in amber, so determined are they to continuing living in the same old way despite whatever personal need for change they may be feeling. The arrival of an unexpected visitor from what might as well be the future begins to loosen some of the perfectly executed stitches which have kept the heroine’s heart constrained all this time but this is less a romance than a gentle blossoming as love of craftsmanship comes to the fore and an artist begins to realise that moving forward does not necessarily entail a betrayal of the past.