A year after his box office smash The Inugami Family, Kon Ichikawa returns to the world of eccentric detective Kosuke Kindaichi with The Devil’s Ballad (悪魔の手毬唄, Akuma no Temari Uta). Like many a Kindaichi mystery, Devil’s Ballad finds him called upon to delve back into the past to satisfy an ageing detective’s anxiety about an old case, only to be faced with a series of new ones as a consequence. This time, however, the mystery leans less on buried secrets than deeply held grudges, betrayals, and lingering feudal feuds as the post-war society tries and fails to free itself from ancient oppressions.

A year after his box office smash The Inugami Family, Kon Ichikawa returns to the world of eccentric detective Kosuke Kindaichi with The Devil’s Ballad (悪魔の手毬唄, Akuma no Temari Uta). Like many a Kindaichi mystery, Devil’s Ballad finds him called upon to delve back into the past to satisfy an ageing detective’s anxiety about an old case, only to be faced with a series of new ones as a consequence. This time, however, the mystery leans less on buried secrets than deeply held grudges, betrayals, and lingering feudal feuds as the post-war society tries and fails to free itself from ancient oppressions.

The film opens with a tryst between two adolescent lovers in the ominously named “Devil’s Skull Village” in 1950. Yasu (Yoko Takahashi), the girl, is at pains to let her boyfriend, Kanao (Koji Kita), know that she is keen to take the relationship to the next level but he is old fashioned and wants to wait until their union is formalised. The pair are interrupted by some of their friends who are in the middle of planning a celebration for a visit from a girl who moved to the city, Chie (Akiko Nishina). Meanwhile, Kindaichi (Koji Ishizaka) has arrived at the inn owned by Kanao’s mother Rika (Keiko Kishi) on invitation from a retired policeman, Isokawa (Tomisaburo Wakayama), who wants Kindaichi to look into the murder of Rika’s husband twenty years ago. Isokawa, then a young rookie, is convinced that Rika’s husband was not the victim but the murderer and the corpse actually belonged to another man entirely – Onda, a drifter who defrauded half the village with a wreath making scam.

Rika and her children – 20-year-old Kanao and his younger sister Satoko (Eiko Nagashima) who has prominent facial birthmarks and rarely leaves the house, came to the village with her husband and are therefore slightly divorced from the longstanding social rivalries. The village has two noble families – the Yuras and the Nires. Feeling the need to modernise, the Nires bet everything on vineyards and it paid off. The Yuras, by contrast, were defrauded by Onda’s wreath scam and lost their fortune and social standing. Yasu, Kanao’s girlfriend, is a daughter of the Yuras, but the Nire’s have been petitioning Rika for quite some time to have her son marry their daughter, Fumiko (Yukiko Nagano), who also has a crush on him (though this is largely irrelevant to her father’s dynastic ambitions). When the younger generation start getting bumped off in ways eerily similar to a local folk song, Kindaichi and Isokawa are on the case, wondering if these new murders have anything to do with their old one.

Despite its 1950 setting, Devil’s Ballad is unusual in resolutely making an irrelevance of the war which only receives a brief mention as an explanation for why some of the case files have been destroyed and for why marriage is such a hot button issue given the lack of men and abundance of women. Nevertheless, the crimes span a turbulent 20 years of Japanese history with the original murder taking place in the early ‘30s during a period of economic instability following the Manchurian Incident. In the socially conservative pre-war era, it seems Onda also got around and may have fathered several illegitimate children with women in the village, some of them noble, some not. These buried secrets seem primed to bubble to the surface now that the children are coming of age and marriage again becomes an issue as worried parents try to think of acceptable ways to block potentially “inappropriate” matches without sending their children off into ruinous elopements or tipping off the wrong people that their kids may not be their kids.

The crimes themselves, old fashioned as they are, are partly reactions to a changing society. We discover that the reason Rika and her husband were forced to come back to the village was that their showbiz careers were stalling – she was a vaudeville performer specialising in shamisen, and he a “benshi” (narrator of silent films) who became convinced his job was obsolete after witnessing a subtitled print of Morocco. Likewise, the two rival families cannot let go of their petty provincial privileges, and as Kanao angrily snaps back at his mother, Japan is now a democratic country and he is free to choose his own wife at a time of his own choosing with or without parental blessing. This remote village is perhaps isolated from the privations of the post-war world but it’s also stuck in the past, hung up on past transgressions and unable to move forward into the new era. However, the primary motivations for murder are as old as time – guilt, humiliation, and self preservation.

Ichikawa keeps things simple but splices in a few strange, avant-garde sequences of kokeshi dolls menacingly bouncing balls coupled with shifts to black and white, fast-paced reaction shots, and stuttering still frame sequences all while Kindaichi showers innocent passersby with his famous dandruff, the idiot police officer continues to offer ridiculous theories while his sergeant dutifully follows him around, and the local bobby perfects a line in hilarious pratfalls. Overlong at two and a half hours and falling prey to the curse of the prestige crime drama in spoiling its mystery through casting, the Devil’s Ballad may not be the best of the Kindaichi mysteries but offers enough of a satisfying twist to prove worthy of the Kindaichi name.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

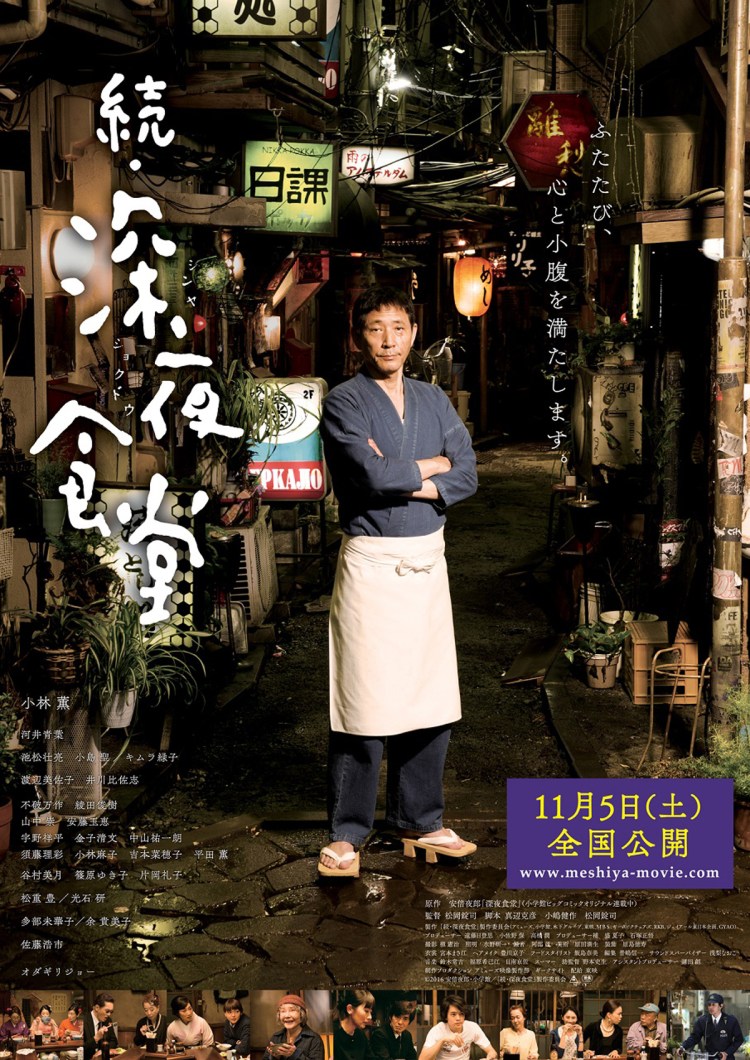

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the

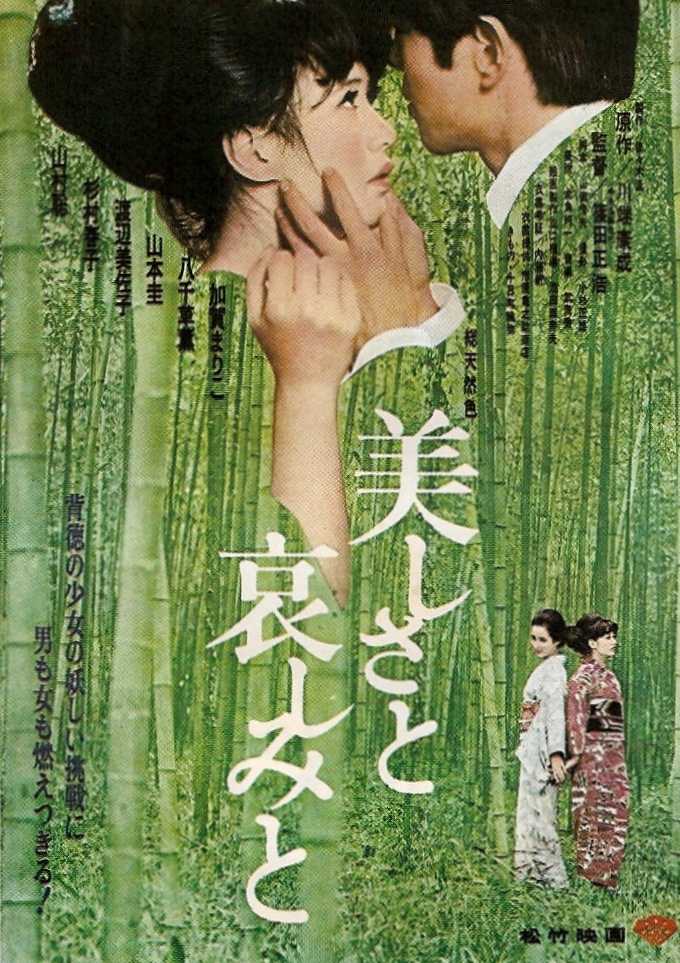

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the  Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession.

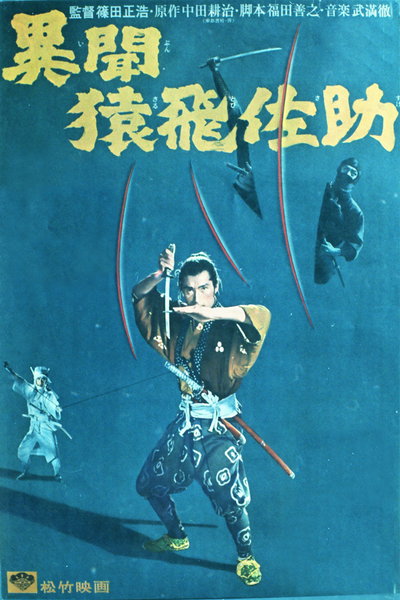

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession. Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost? Kwaidan (怪談) is something of an anomaly in the career of the humanist director Masaki Kobayashi, best known for his wartime trilogy The Human Condition. Moving away from the naturalistic concerns that had formed the basis of his earlier career, Kwaidan takes a series of ghost stories collected by the foreigner Lafcadio Hearn and gives them a surreal, painterly approach that’s somewhere between theatre and folktale.

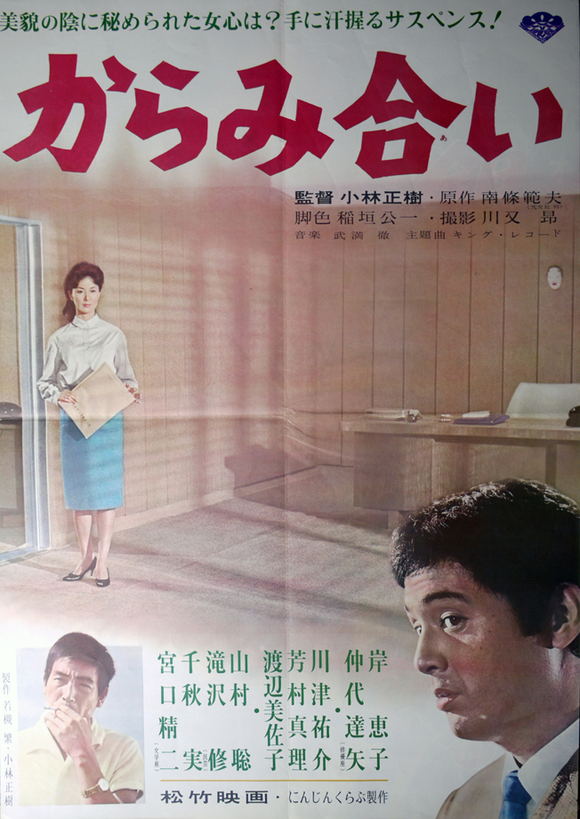

Kwaidan (怪談) is something of an anomaly in the career of the humanist director Masaki Kobayashi, best known for his wartime trilogy The Human Condition. Moving away from the naturalistic concerns that had formed the basis of his earlier career, Kwaidan takes a series of ghost stories collected by the foreigner Lafcadio Hearn and gives them a surreal, painterly approach that’s somewhere between theatre and folktale. Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.

Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.