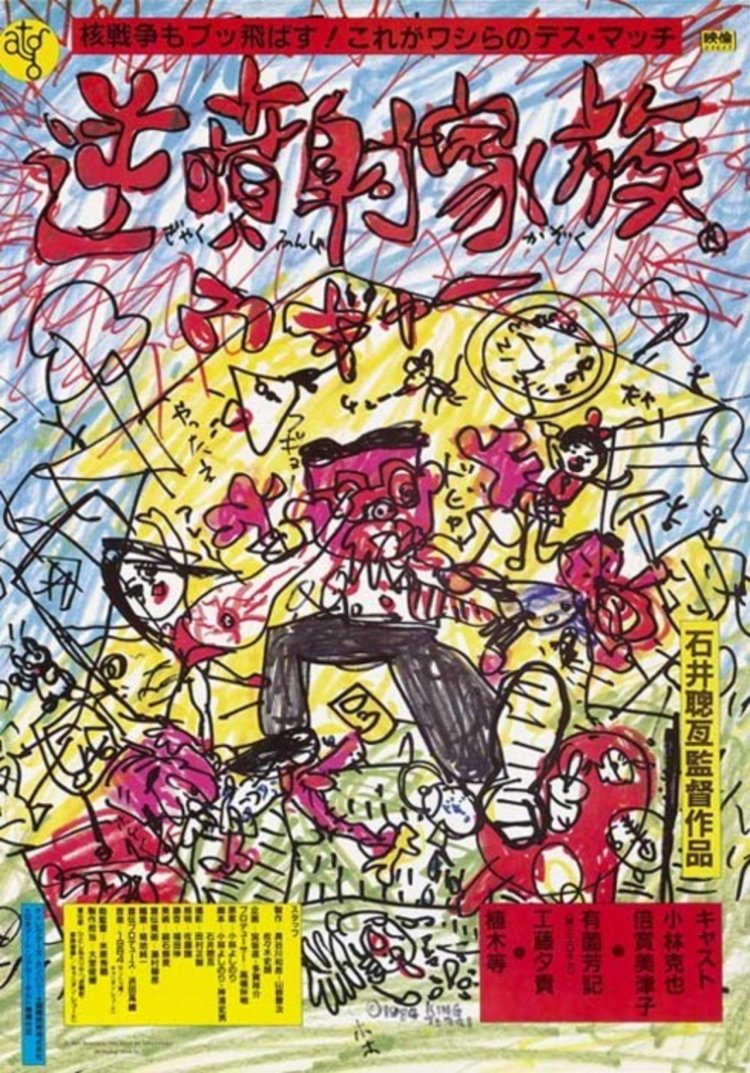

The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s The Family Game, released in 1983, kick started this re-examination of the primary social unit through attacking it Teorema-style as the family’s tutor rips through their generic middle-class existence by adopting each of their pre-defined social roles in turn. One year later Sogo Ishii’s The Crazy Family (逆噴射家族, Gyakufunsha Kazoku) turns the director’s punk aesthetic to a similar theme but this time the family destroys itself in its earnestness to live the Japanese dream in the increasing economic possibility of the pre-bubble era. The Kobayashis are the perfect example of the “typical” aspiring family, but what is the “sickness” that the family patriarch is so afraid of, who (or what) is it that is sick, and if it is possible to be “cured” what would such a cure look like?

The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s The Family Game, released in 1983, kick started this re-examination of the primary social unit through attacking it Teorema-style as the family’s tutor rips through their generic middle-class existence by adopting each of their pre-defined social roles in turn. One year later Sogo Ishii’s The Crazy Family (逆噴射家族, Gyakufunsha Kazoku) turns the director’s punk aesthetic to a similar theme but this time the family destroys itself in its earnestness to live the Japanese dream in the increasing economic possibility of the pre-bubble era. The Kobayashis are the perfect example of the “typical” aspiring family, but what is the “sickness” that the family patriarch is so afraid of, who (or what) is it that is sick, and if it is possible to be “cured” what would such a cure look like?

Mr and Mrs Kobayashi have achieved their dream – getting out of the danchi and into a suburban house that they own (or will own, once the mortgage is paid off) outright. Mr. Kobayashi, Katsukuni (Katsuya Kobayashi), is a typical salaryman while his wife Saeko (Mitsuko Baisho) stays at home to look after their two children – middle schooler Erika (Yuki Kudo) and her older brother Masaki (Yoshiki Arizono), currently a “ronin” studying to retake his university entrance exams determined to get into the prestigious Tokyo University.

Blissfully happy, the family are adapting well enough to their new home but there’s always that lingering feeling of impending doom, as if all this is too good to be true. Sure enough, Masaki’s adoption of a stray dog alerts the family to a more serious problem – termites. Suddenly terrified that something is literally trying to eat his house out from under him, Katsukuni goes on a fumigating rampage but the termites are not the only source of tension. Turning up right on time, grandpa arrives for a visit after falling out with Katsukuni’s older brother with whom he’d been living. The Kobayashis moved so that the kids could finally have their own rooms (and mum and dad some privacy) but grandpa shows no signs of leaving meaning Katsukuni is sharing with his dad and Saeko has been relegated to Erika’s room.

The house is what the family has always dreamed of – owning one’s own home is no mean feat for those raised in the post-war era, but it’s still a small environment for five people even if much nicer than their tiny city flat. More than just a structure it represents everything the ordinary family dreams of – peace, prosperity, harmony and a life lived in tune with the social order. Katsukuni’s fears that a mysterious “sickness” is plaguing his loved ones is a sign of his discomfort with this ordered way of living. Despite their stereotypical qualities, there is something not exactly right about each of his “ordinary” family members – mum stripteases for grandad’s friends, precocious teenage daughter Erika is not sure if she wants to be a pro-wrestler or an idol and spends all of her time “idolising” her favourite stars, and son Masaki has become a proto-hikikomori so obsessed with studying that he’s taken to stabbing himself in the leg every time he starts to nod off so that he can keep hitting the books rather than the hay.

Yet for all that it’s Katsukuni himself who is the most “sick” in his inability to reconcile himself to social conformity. Despite being apparently successful, he has deep seated feelings of inadequacy which convince him that something is going to go wrong with the family he feels a duty to protect. Wanting to be a good husband and father, Katsukuni thinks he has to “cure” his family of their strange behaviours and make them the sort of people who live in nice houses in the suburbs, but only succeeds in driving himself out of his mind.

Grandpa’s antics have the other family members well and truly fed up but Katsukuni feels just as much filial piety as he does responsibility towards his own children and cannot bring himself to tell his father to go and so he hits on an extreme solution – he’s going to dig a basement, by hacking up the living room floor and pushing downwards, towards hell. Surprise, surprise, his dream home is atop a nest of termites, the bugs are literally working their way in but, ironically enough, Katsukuni is the biggest termite of them all as his very own “hill” begins to appear just in front of the sofa while he tries to find a space for the older generation in a modern home.

Grandpa is an unwelcome manifestation of the inescapable past. When everything goes to hell and the house becomes a battlefield, grandpa manages to dig out his wartime uniform complete with a sword and attempts to assume command by dividing the house into sectors before capturing and trussing his own granddaughter whom he then threatens to rape and torture, apparently eager to revisit his Manchurian military service and all of its implied cruelties. When Katsukuni believes that all is lost and his family can’t be saved he opts for the most culturally appropriate solution – group suicide, but his family won’t play along. Paranoid and delusional, they turn on each other, defending themselves with icons of their respective roles, venting their frustrations and long held grudges in one prolonged battle of violent madness.

When the air finally clears there is only one solution – the house has to go. The desire for a “conventional life” or the feeling of not achieving it is, in that sense, “the sickness” which has infected the Kobayashi family. The finale sees them finally living happily once again but literally “outside” of the mainstream, in a totally open world where there is space for everyone – all quirks embraced, all extremes born. Everyone has their place but the family remains whole, freed from the burden of chasing an unrealisable dream.

A short musical clip from the film

Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from

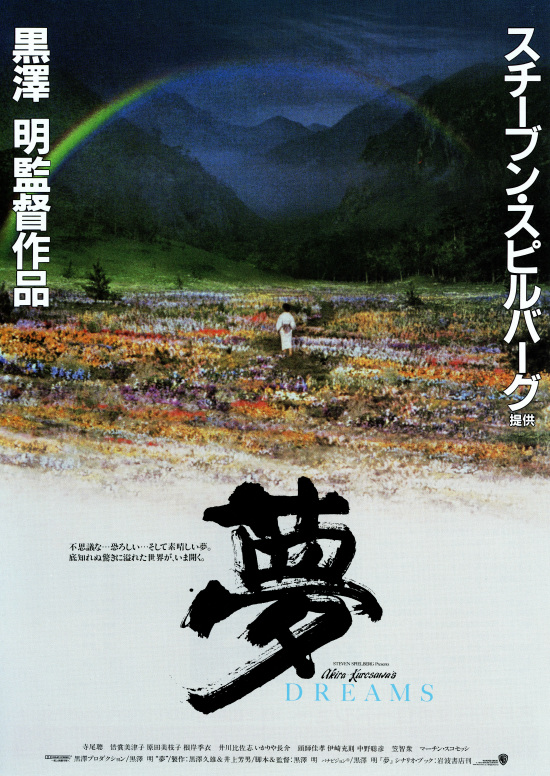

Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from  Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced.

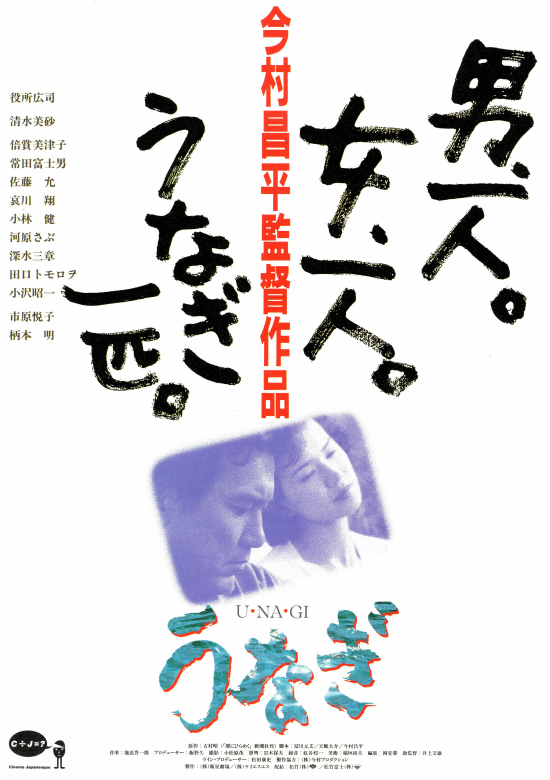

Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced. Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come. Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment.

Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment. It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own.

It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own.