Seijun Suzuki had been directing for seven years and had made almost 20 films by the time he got to 1963’s Youth of the Beast (野獣の青春, Yaju no Seishun). Despite his fairly well established career as a director, Youth of the Beast is often though to be Suzuki’s breakthrough – the first of many films displaying a recognisable style that would continue at least until the end of his days at Nikkatsu when that same style got him fired. Building on the frenetic, cartoonish noir of Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards!, Suzuki once again casts Jo Shishido in the the lead only this time as an even more ambiguous figure playing double agent to engineer a gang war between two rival hoodlums.

Seijun Suzuki had been directing for seven years and had made almost 20 films by the time he got to 1963’s Youth of the Beast (野獣の青春, Yaju no Seishun). Despite his fairly well established career as a director, Youth of the Beast is often though to be Suzuki’s breakthrough – the first of many films displaying a recognisable style that would continue at least until the end of his days at Nikkatsu when that same style got him fired. Building on the frenetic, cartoonish noir of Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards!, Suzuki once again casts Jo Shishido in the the lead only this time as an even more ambiguous figure playing double agent to engineer a gang war between two rival hoodlums.

Suzuki opens in black and white as the bodies of a man and a woman are discovered by a small team of policemen. Finding a note from the deceased female which states that she settled on taking her own life because she loved her man and thought death was the only way to keep him, the police assume it’s an ordinary double suicide or perhaps murder/suicide but either way not worthy of much more attention, though discovering a policeman’s warrant card on the nightstand does give them pause for thought.

Meanwhile, across town, cool as ice petty thug Jo Mizuno (Jo Shishido) is making trouble at a hostess bar but when he’s taken to see the boss, it transpires he was really just making an audition. The Nomoto gang take him in, but Mizuno uses his new found gang member status to make another deal with a rival organisation, the Sanko gang, to inform on all the goings on at Nomoto. So, what is Mizuno really up to?

As might be expected, that all goes back to the first scene of crime and some suicides that weren’t really suicides. Mizuno had a connection with the deceased cop, Takeshita (Ichiro Kijima), and feels he owes him something. For that reason he’s poking around in the local gang scene which is, ordinarily, not the sort of world straight laced policeman Takeshita operated in which makes his death next to a supposed office worker also thought to be a high class call girl all the stranger.

Like Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards!, Youth of the Beast takes place in a thoroughly noirish world as Mizuno sinks ever deeper into the underbelly trying to find out what exactly happened to Takeshita. Also like Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards!, Youth of the Beast is based on a novel by Haruhiko Oyabu – a pioneer of Japanese hardboiled whose work provided fertile ground for many ‘70s action classics such as The Beast Must Die and Resurrection of the Golden Wolf, but Suzuki’s ideas of noir owe a considerable debt to the gangster movies of the ‘30s rather than the moody crime dramas of twenty years later.

Jo Shishido’s Mizuno is a fairly typical ‘40s conflicted investigator, well aware of his own flaws and those of the world he lives in but determined to find the truth and set things right. The bad guys are a collection of eccentrics who have more in common with tommy gun toting prohibition defiers than real life yakuza and behave like cartoon villains, throwing sticks of dynamite into moving cars and driving off in hilarious laughter. Top guy Nomoto (Akiji Kobayashi) wears nerdy horn-rimmed glasses that make him look like an irritated accountant and carries round a fluffy cat he likes to wipe his knives on while his brother Hideo (Tamio Kawaji), the fixer, is a gay guy with a razor fetish who likes to carve up anyone who says mean stuff about his mum. The Sanko gang, by contrast, operate out of a Nikkatsu cinema with a series of Japanese and American films playing on the large screen behind their office.

The narrative in play may be generic (at least in retrospect) but Suzuki does his best to disrupt it as Mizuno plays the two sides against each other and is often left hiding in corners to see which side he’s going to have to pretend to be on get out of this one alive. Experimenting with colour as well as with form, Suzuki progresses from the madcap world of Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards! to something weightier but maintains his essentially ironic world view for an absurd journey into the mild gloom of the nicer end of the Tokyo gangland scene.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

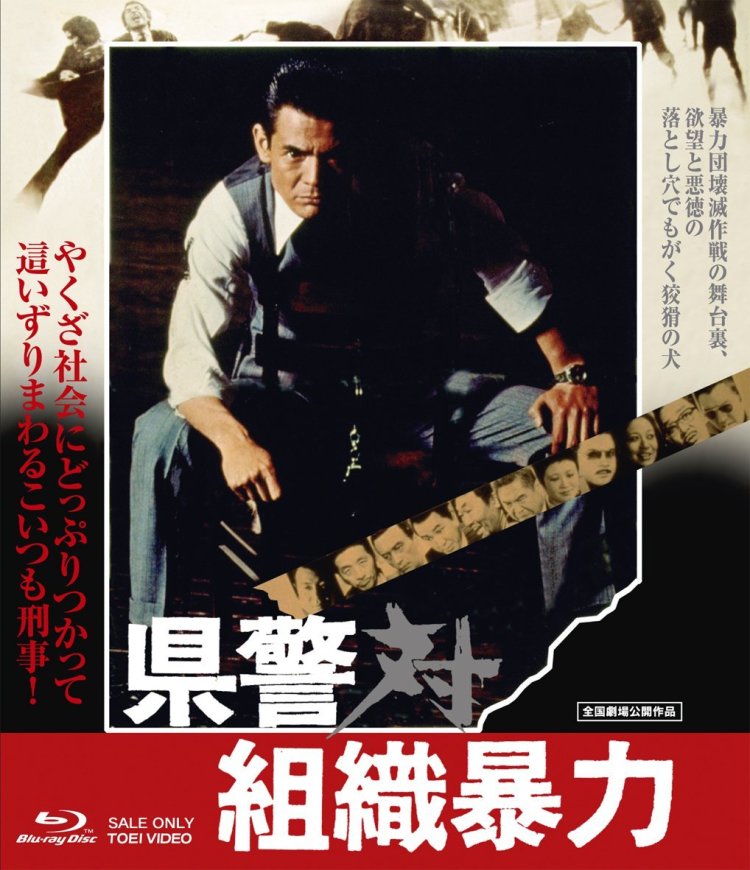

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first

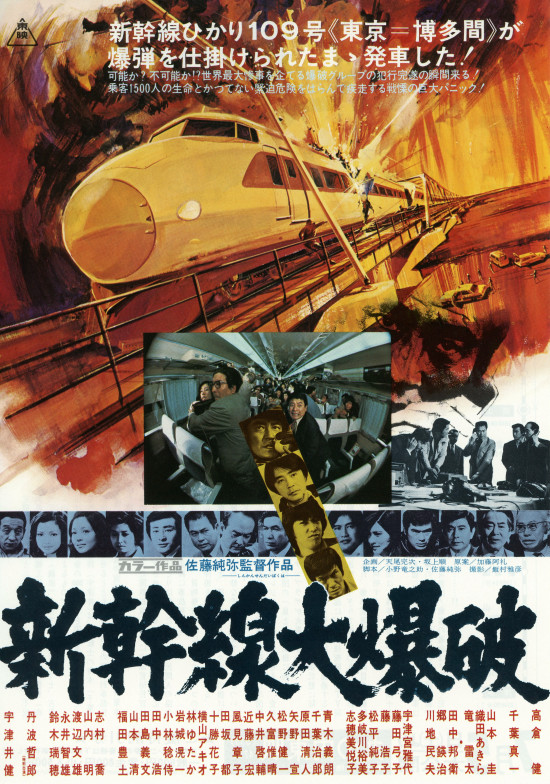

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first  For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further. Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.

Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy. The Snow Woman is one of the most popular figures of Japanese folklore. Though the legend begins as a terrifying tale of an evil spirit casting dominion over the snow lands and freezing to death any men she happens to find intruding on her territory, the tale suddenly changes track and far from celebrating human victory over supernatural malevolence, ultimately forces us to reconsider everything we know and see the Snow Woman as the final victim in her own story. Previously brought the screen by Masaki Kobayashi as part of his

The Snow Woman is one of the most popular figures of Japanese folklore. Though the legend begins as a terrifying tale of an evil spirit casting dominion over the snow lands and freezing to death any men she happens to find intruding on her territory, the tale suddenly changes track and far from celebrating human victory over supernatural malevolence, ultimately forces us to reconsider everything we know and see the Snow Woman as the final victim in her own story. Previously brought the screen by Masaki Kobayashi as part of his  You know how it is, when you’re from a small town perhaps you feel like a big fish but when you swim up to the great lake that is the city, you suddenly feel very small. Natsume has come to Tokyo from her rural backwater town in Kagoshima to look for her boyfriend, Umi, who’s not been in contact (even with his parents). When she arrives at the patisserie he’d been working at she discovers that he suddenly quit a while ago without telling anyone where he was going. Natsume is distressed and heartbroken but notices that the cafe is currently hiring and so asks if she may take Umi’s place – after all she grew up helping out at her family’s cake shop!

You know how it is, when you’re from a small town perhaps you feel like a big fish but when you swim up to the great lake that is the city, you suddenly feel very small. Natsume has come to Tokyo from her rural backwater town in Kagoshima to look for her boyfriend, Umi, who’s not been in contact (even with his parents). When she arrives at the patisserie he’d been working at she discovers that he suddenly quit a while ago without telling anyone where he was going. Natsume is distressed and heartbroken but notices that the cafe is currently hiring and so asks if she may take Umi’s place – after all she grew up helping out at her family’s cake shop!