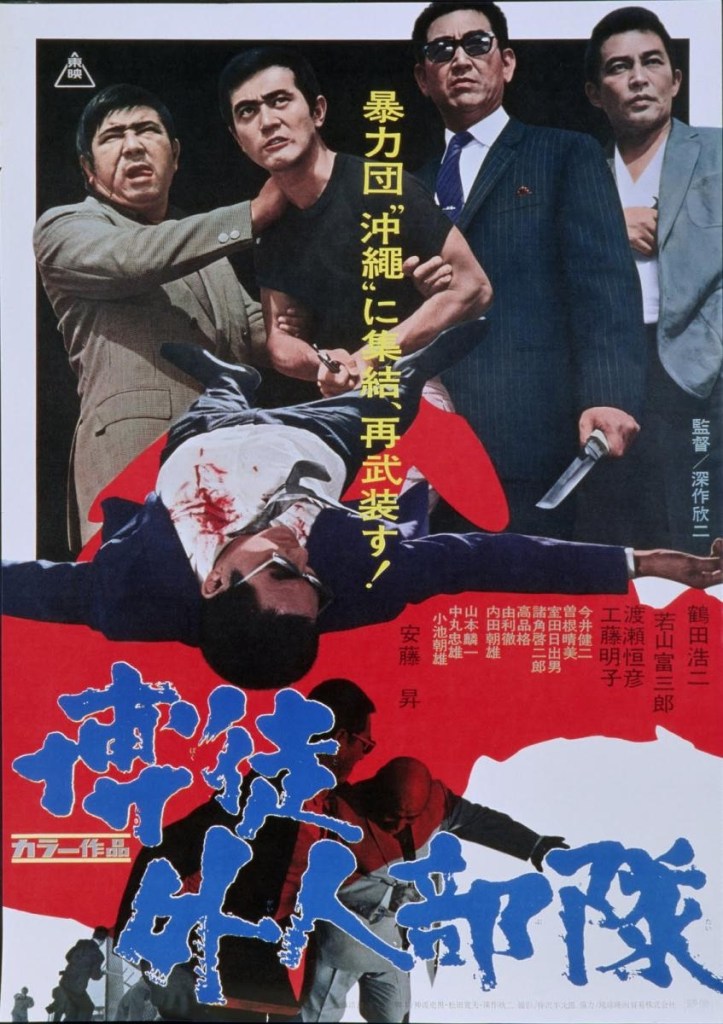

A yakuza just out of jail emerges into a very different Japan in Kinji Fukasaku’s proto-jitsuroku gangster picture, Japan Organized Crime Boss (日本暴力団 組長, Nihon Boryoku-dan: Kumicho). A contemporary Oda Nobunaga is trying to unify the nation under his yakuza banner while fostering a nationalist agenda and colluding with corrupt politicians to prop up the 1970 renewal of the Anpo security treaty, but as it turns out some people aren’t very interested in revolutions of any kind save the opportunity to live a quiet life they once feared would elude them.

As the film opens, a narratorial voice explains that the nation has now escaped from post-war chaos, but Japan’s increasing prosperity has led to a natural decline of the yakuza which has seen some try to ride the rising tides to find new ways to prosper. Exploiting its control of local harbours, the Danno group has quickly expanded though Osaka and on to the rest of the nation thanks largely to its strategist, Tsubaki (Ryohei Uchida), and his policy of convincing local outfits to ally with them and fight as proxies allowing Danno to escape all responsibility for public street violence.

Perhaps strangely, the Danno group and others are acutely worried about optics and keen to present themselves as legitimate businessmen while using a prominent politician as a go-between to settle disputes between gangs. The yakuza already know they’re generally unpopular and fear that attracting too much attention will only bring them problems from the authorities. The politician needs Danno to look clean so that they can back them in opposing the protests against the Anpo treaty, while the yakuza organisation is later depicted as a militarised wing of the far right hoping to correct “misguided” post-war democracy while eradicating communism and instilling a sense of patriotic pride as they go. Of course, all of that will also likely be good for business while quite clearly marking these new conspiracy-minded yakuza as “bad”, hypocritical harbingers of a dangerous authoritarianism.

Tsukamoto (Koji Tsuruta), the recently released lieutenant of the Hamanaka gang, is conversely the representative of the “good” yakuza who still care about the code and are genuinely standing up for the little guy against the oppressive forces now represented by bad yakuza. Hamanaka had allied with Danno while Tsukamoto was inside and was thereafter targeted by the local Sakurada group who have joined the Tokyo Alliance of yakuza clans opposed to Danno who continue to fight them by proxy. After his boss is killed and tells him that joining Danno was a mistake, Tsukamoto’s first thought is to rebuild the clan which he does by remaining neutral, refusing to engage in Danno’s proxy wars while protecting his men from their violence as mediated by the completely unhinged, drug-addled Miyahara (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and the anarchic Hokuryu gang.

Miyahara comes round to Tsukamoto precisely because of his pacifist philosophy after he kidnaps one of his men and Tsukamoto stands up to him while making a point of not fighting back. As crazed as he is, Miyahara is a redeemable gangster who later also turns on Danno regretting having agreed to do their dirty work for relatively little reward. After a gentle romance with the sister of a fallen comrade, Tsukamoto, who lost his first wife to suicide while inside, begins to dream of leaving the life behind but as he and others discover there is no real out from the yakuza and the code must always be repaid. In failing to protect his clan he fails to save himself and becomes a kind of martyr for the ninkyo society taking on politicised yakuza and their lingering militarism.

Fukasaku takes a typical ninkyo plot of a noble gangster standing up for what he believes is right against the forces of corruption and begins to undercut it with techniques such as voiceover narration and onscreen text that he’d later use in the jitsuroku films of the 1970s which firmly reject the idea of yakuza nobility seeing them instead as destructive forces born of post-war chaos and increasingly absurd in a Japan of rising economic prosperity. Men like Tsukamoto are it seems at odds with their times, unable to survive in the new society in which there is no longer any honour among thieves only hypocrisy and self-interest.

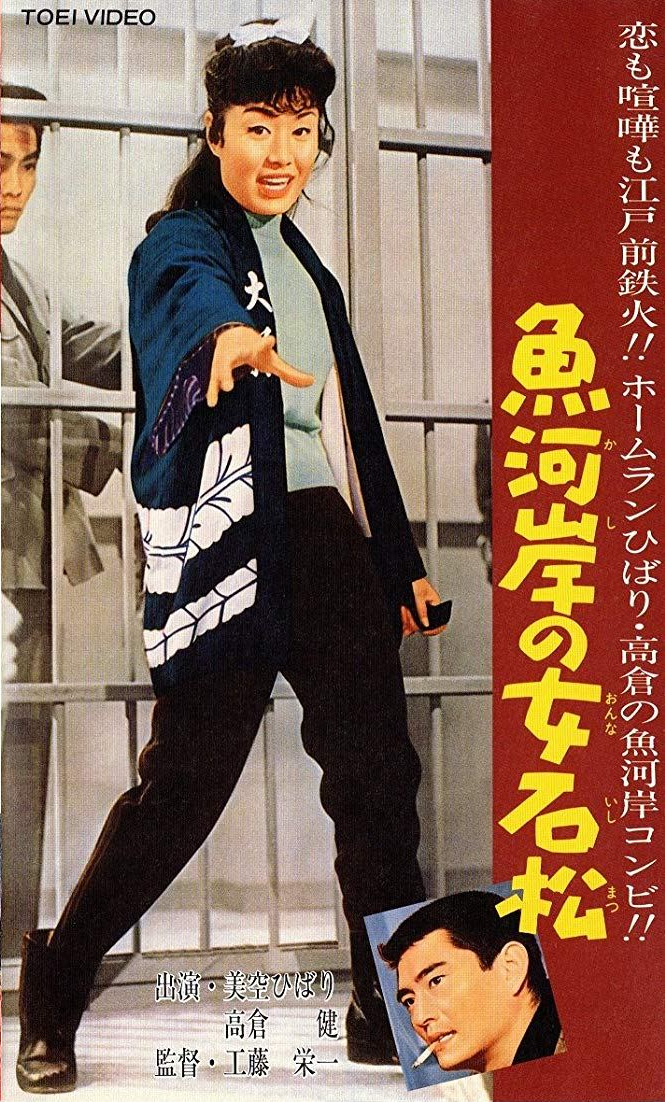

Brutal Tales of Chivalry (昭和残侠伝, Showa Zankyo-den) – a title which neatly sums up the “ninkyo eiga”. These old school gangsters still feel their traditional responsibilities deeply, acting as the protectors of ordinary people, obeying all of their arcane rules and abiding by the law of honour (if not the laws of the state the authority of which they refuse to fully recognise). Yet in the desperation of the post-war world, the old ways are losing ground to unscrupulous upstarts, prepared to jettison their long-held honour in favour of a dog eat dog mentality. This is the central battleground of Kiyoshi Saeki’s 1965 film which looks back at the immediate post-war period from a distance of only 15 years to ask the question where now? The city is in ruins, the people are starving, women are being forced into prostitution, but what is going to be done about it – should the good people of Asakusa accept the rule of violent punks in return for the possibility of investment in infrastructure, or continue to struggle through slowly with the old-fashioned patronage of “good yakuza” like the Kozu Family?

Brutal Tales of Chivalry (昭和残侠伝, Showa Zankyo-den) – a title which neatly sums up the “ninkyo eiga”. These old school gangsters still feel their traditional responsibilities deeply, acting as the protectors of ordinary people, obeying all of their arcane rules and abiding by the law of honour (if not the laws of the state the authority of which they refuse to fully recognise). Yet in the desperation of the post-war world, the old ways are losing ground to unscrupulous upstarts, prepared to jettison their long-held honour in favour of a dog eat dog mentality. This is the central battleground of Kiyoshi Saeki’s 1965 film which looks back at the immediate post-war period from a distance of only 15 years to ask the question where now? The city is in ruins, the people are starving, women are being forced into prostitution, but what is going to be done about it – should the good people of Asakusa accept the rule of violent punks in return for the possibility of investment in infrastructure, or continue to struggle through slowly with the old-fashioned patronage of “good yakuza” like the Kozu Family? Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.

Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.