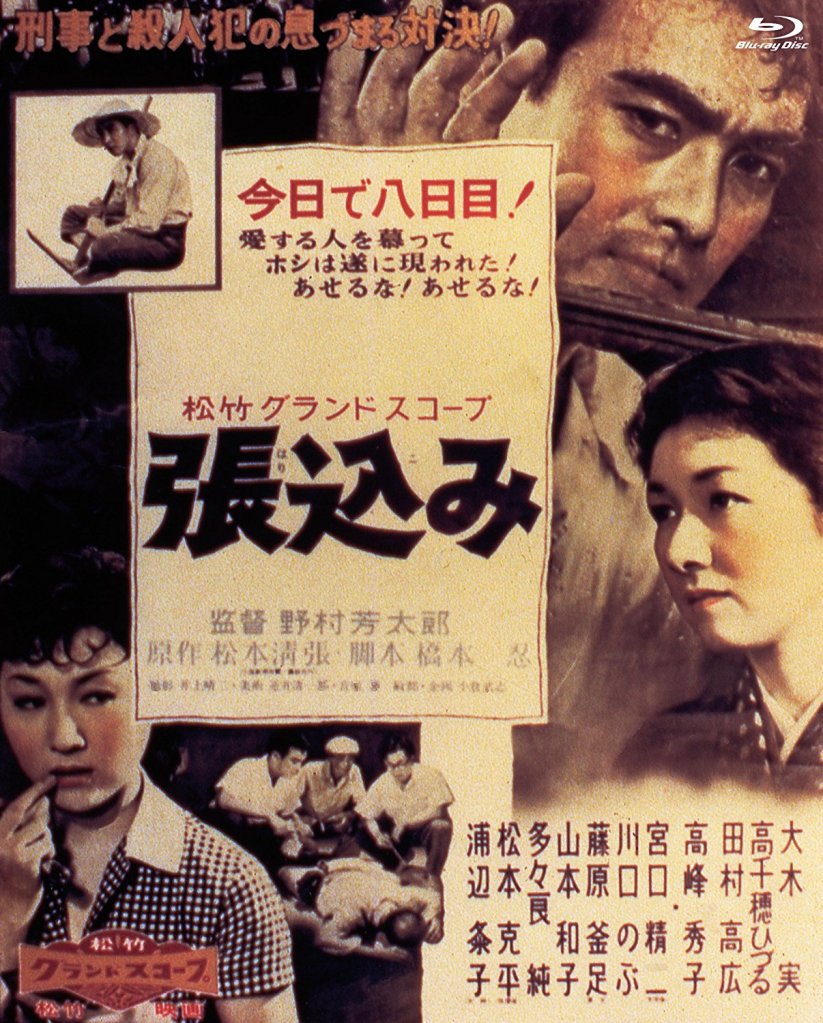

Most closely associated with the crime genre, Yoshitaro Nomura was, like his frequent source of inspiration Seicho Matsumoto, also an insightful chronicler of the lives of ordinary people in the complicated post-war society. Stakeout (張込み, Harikomi), once again inspired by a Matsumoto short story, is on the surface a police procedural but underneath it’s not so much about the fugitive criminal as a policeman on the run, vacillating in his choice of bride, torn between the woman he loves who is afraid to marry him because her family is poor, and the pressure to accept an arranged marriage with the perfectly nice daughter of a local bathhouse. The stakeout becomes, in his eyes, a kind of illustrated parable, going against the socially conventional grain to convince him that making the “sensible” choice may only lead to long years of regret, misery, and loneliness.

The film opens, as so many of Nomura’s films do, with a journey as two dogged Tokyo cops board a long distance train from Yokohoma travelling all the way down to provincial Kyushu which might as well be a world away from the bustling metropolis. Posing as motor salesmen, they take a room at a local inn overlooking the home of a melancholy housewife, Sadako (Hideko Takamine), the former girlfriend of a man on the run, Ishii (Takahiro Tamura), suspected of being in possession of a gun used to kill the owner of a pawn shop during a robbery. The younger of the policemen, Yuki (Minoru Oki), declares himself faintly disappointed with Sadako, complaining that she looks older than her years and is in fact quite boring, “the epitome of ordinary”.

His older colleague, Shimooka (Seiji Miyaguchi), reminds him that most people are boring and ordinary, but as he watches her Yuki comes to feel a kind of sympathy for Sadako, seeing her less as a suspect than a fellow human being. Later we hear from Sadako that her marriage has left her feeling tired every day, aimless, and with nothing to live for, that her decision to marry was like a kind of suicide. “A married woman is miserable” Yuki laments on observing Sadako’s life as she earnestly tries to do her best as a model housewife, married to a miserly middle-aged banker who padlocks the rice, berates her for not starting the bath fire earlier to save on coal, and gives only 100 yen daily in housekeeping money while she cares for his three children from a previous marriage. Trying to coax him back towards the proper path, Shimooka admits that marriage is no picnic, but many are willing to endure hardship at the side of the right man.

The “right man” gets Yuki thinking. Sadako has obviously not ended up with the right man which is why he sees no sign of life in her as if she simply sleepwalks through her existence. He is obviously keen that he wouldn’t want to make another woman feel like that, or perhaps that he would not like to be left feeling as she does at the side of the wrong woman. We discover that his dilemma is particularly acute because he finds himself at a crossroads dithering between two women, faced with a similar choice to the one he increasingly realises Sadako regrets. Shimooka’s wife is acting as a go-between, pressuring him to agree to an arranged marriage with a very nice girl whose family own the local bathhouse. She makes it clear that she’s not trying to force him into a marriage he doesn’t want, but would like an answer even if the answer is no so they can all move forward, but for some reason he hasn’t turned it down. Yuki is in love with Yumiko (Hizuru Takachiho), but Yumiko has turned him down once before because her family is desperately poor, so much so that they’re about to be evicted and all six of them will have to move into a tiny one room flat. She feels embarrassed to explain to her prospective husband that she will need to continue working after they marry but send almost all of her money to her parents rather than committing to their new family.

Meditating on his romantic dilemma, Yuki begins to sympathise even more with Sadako, resenting their fugitive for having placed her in such a difficult position and repeatedly cautioning the other officers to make sure that the press don’t get hold of Sadako’s name and potentially mess up her comfortable middle class life with scandal when she is entirely blameless. The fugitive, Ishii, is not a bad man but a sorry and desperate one. He went to Tokyo to find work, but became one of many young men lost in the complicated post-war economy, shuffling from one poorly paid casual job to another. Now suffering with what seems to be incurable tuberculosis, he finds himself dreaming of his first love, the gentle tones of famous folksong Furusato wafting over the pair as they lament lost love at a picturesque hot springs while Yuki continues to spy on them from behind a nearby tree.

They both bitterly regret their youthful decision to part, she not to go and he not to stay. The failure to fight for love is what has brought them here, to lives of desperate and incurable misery filled only with regret and lonliness. Sadako views her present life as a kind of punishment, finally resolving to leave her husband and runaway with Ishii who has told her that he plans to go to Okinawa to drive bulldozers for the next three years, though we can perhaps guess he has a different destination in mind. “That’s the way the world is, things don’t go the way you want” Ishii laments, but the truth is choices have already been made and your course is as set as a railway track. Sadako plots escape, but all Yuki can do is send her back to her husband with sympathy and train fare, leaving us worried that perhaps she won’t go back after all. Buying tickets for his own return journey, Yuki pauses to send a telegram. He’s made his choice. It’s not the same as Sadako’s, a lesson has been learnt. He goes back to Tokyo with marriage on his mind, but does so with lightness in his step in walking away from the socially rigid past towards a freer future, staking all on love as an anchor in an increasingly confusing world.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Looking from the outside in, the Tokyo of 1960 seems to have been one of rising economic prosperity in which post-war anxiety was beginning to transition into a relentless surge towards modernity, but there also seems to have been a mild preoccupation with the various dangers that same modernity might present. Like

Looking from the outside in, the Tokyo of 1960 seems to have been one of rising economic prosperity in which post-war anxiety was beginning to transition into a relentless surge towards modernity, but there also seems to have been a mild preoccupation with the various dangers that same modernity might present. Like

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.

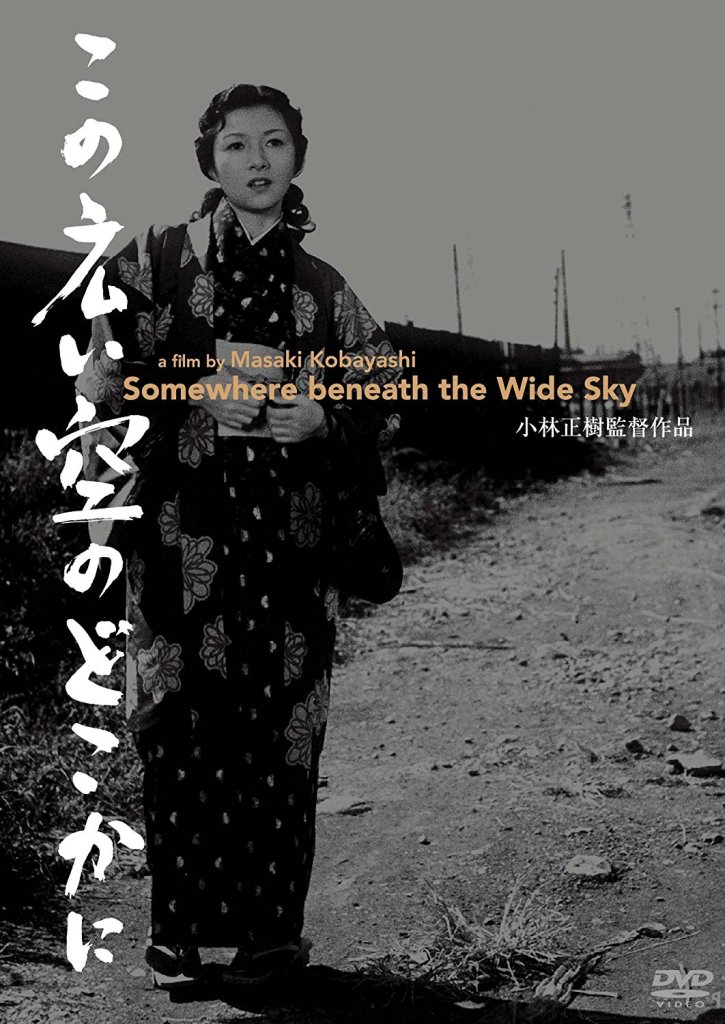

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly. Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –  Things take a slight detour in the third of the Outlaw series this time titled “Heartless” (大幹部 無頼非情, Daikanbu Burai Hijo). Rather than picking up where we left Goro – collapsed on a high school volleyball court, it’s now 1956 and we’re with a guy called “Goro the Assassin” but it’s not exactly clear is this is a side story or perhaps an entirely different continuity for the story of the noble hearted gangster we’ve been following so far. The only constant is actor Tetsuya Watari who once again plays Goro Fujikawa but in an even more confusing touch the supporting characters are played by many of the actors who featured in the first two films but are actually playing entirely different people….

Things take a slight detour in the third of the Outlaw series this time titled “Heartless” (大幹部 無頼非情, Daikanbu Burai Hijo). Rather than picking up where we left Goro – collapsed on a high school volleyball court, it’s now 1956 and we’re with a guy called “Goro the Assassin” but it’s not exactly clear is this is a side story or perhaps an entirely different continuity for the story of the noble hearted gangster we’ve been following so far. The only constant is actor Tetsuya Watari who once again plays Goro Fujikawa but in an even more confusing touch the supporting characters are played by many of the actors who featured in the first two films but are actually playing entirely different people…. So, as it turns out the end of

So, as it turns out the end of