After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

Three months after nine people were drowned when a local ferry sank in the harbour, friends and relatives of the dead begin to receive messages signed by their loved ones instructing them to be at a small island at midnight. Cruel joke or not, each of the still grieving recipients makes their way to the boathouse, clutching the desperate hope that the dead will really return to them. Sure enough, on the stroke of midnight the ghostly boat rises from the ocean floor bringing a collection of lost souls with it, but its stay is a temporary one – just long enough to say goodbye.

Obayashi once again begins the film with an intertile-style message to the effect that sometimes meetings are arranged just to say goodbye. He then includes two brief “prequel” sequences to the contemporary set main narrative. The first of these takes place ten years previously in which a boy called Mitsugu throws a message wrapped around a rock into a school room where his friend Noriko is studying. We then flash forward to three months before the main action, around the time of the boat accident, where an assassination attempt is made on the life of a local gangster in a barber shop. At first the connection between these events is unclear as messages begin to arrive in innovative ways in the film’s “present”. After a while we begin to realise that the recipients of the messages are so shocked to receive them because they believe the senders to be dead.

At three months since the sinking, the grief is still raw and each of our protagonists has found themselves trapped in a kind of inertia, left alone so suddenly without the chance to say goodbye. The left behind range from a teenager whose young love story has been severed by tragedy, a middle aged man who lost a wife and daughter and now regrets spending so much time on something as trivial as work, a middle aged trophy wife and the colleague who both loved a successful businessman, two swimmers with unresolved romances, and the yakuza boss who lost his wife and grandson. For some the desire is to join their loved ones wherever it is that they’re going, others feel they need to live on with double the passion in the name of the dead but they are all brought together by a need to meet the past head on and come to terms with it so that they can emerge from a living limbo and decide which side of the divide they need to be on.

Aside from the temporary transparency of the border between the mortal world and that of the dead, the living make an intrusion in the form of the ongoing yakuza gang war. The Noriko (Kaori Takahashi) from the film’s prequel sequence also ends up at the meeting point through sheer chance, as does the Mitsugu (Yasufumi Hayashi), now a gangster and charged with the unpleasant task of offing the old man despite his longstanding debt of loyalty to him. These are the only two still living souls brought together by an unresolved message bringing the events full circle as they achieve a kind of closure (with the hope of a new beginning) on their frustrated childhood romance.

The other two hangers on, an ambitious yakuza with a toothache played by frequent Obayashi collaborator Ittoku Kishibe, and a lunatic wildcat sociopath played by the ubiquitous Tomorowo Taguchi, are more or less comic relief as they hide out in the forrest confused by the massing group of unexpected visitors who’ve completely ruined their plot to assassinate the old yakuza boss and assume control of the clan. However, they too are also forced to face the relationship problems which bought them to this point and receive unexpected support from the boss’ retuned spouse who points out that this situation is partly his own fault for failing to appreciate the skills of each of his men individually. The boss decides to make a sacrifice in favour of the younger generation but his final acts are those of forgiveness and a plea for those staying behind to forget their differences and work together.

Revisiting Obayashi’s frequent themes of loss and the need to keep living after tragedy strikes, Goodbye For Tomorrow is a melancholy character study of the effects of grief when loved ones are taken without the chance for goodbyes. Aside from the earliest sepia tinged sequence, Obayashi plays with colour less than in his other films but manages to make the improbable sight of the sunken boat rising from the bottom of the sea genuinely unsettling. The supernatural mixes with the natural in unexplained ways and Obayashi even makes room for The Little Girl Who Conquered Time’s Tomoyo Harada as a mysterious spirit of loneliness, as well as a cameo for ‘80s leading man Toshinori Omi. The Japanese title of the film simply means “tomorrow” which gives a hint as to the broadly positive sense of forward motion in the film though the importance “goodbye” is also paramount. The slight awkwardness of the English title is therefore explained – saying goodbye to yesterday is a painful act but necessary for tomorrow’s sake.

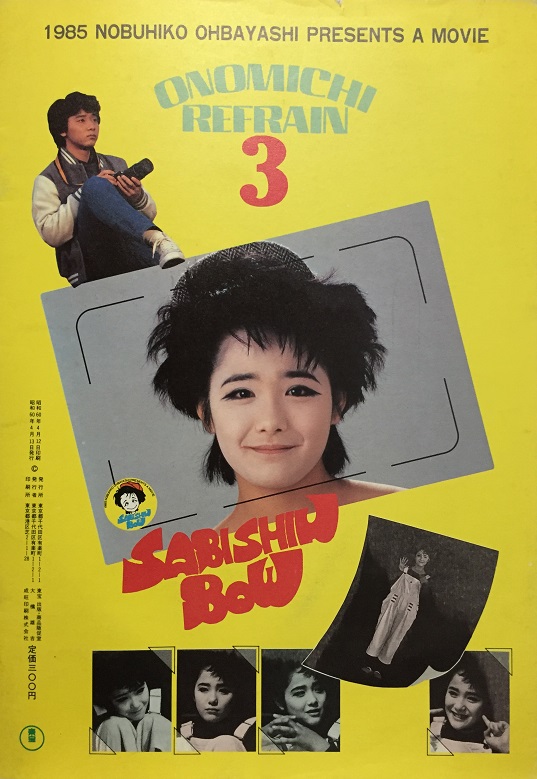

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie. Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be.

Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be. Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape.

Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape. Nobuhiko Obayashi might be most closely associated with his debut, Hausu, which takes the form of a surreal, totally psychedelic haunted house movie, but in many ways his first feature is not particularly indicative of the rest of Obayashi’s output. 1984’s The Deserted City (AKA Haishi, 廃市), is a much better reflection of the director’s most prominent preoccupations as it once again sees the protagonist taking a journey of memory back to a distant youth which is both forgotten in name yet ever present like an anonymous ghost haunting the narrator with long held regrets and recriminations.

Nobuhiko Obayashi might be most closely associated with his debut, Hausu, which takes the form of a surreal, totally psychedelic haunted house movie, but in many ways his first feature is not particularly indicative of the rest of Obayashi’s output. 1984’s The Deserted City (AKA Haishi, 廃市), is a much better reflection of the director’s most prominent preoccupations as it once again sees the protagonist taking a journey of memory back to a distant youth which is both forgotten in name yet ever present like an anonymous ghost haunting the narrator with long held regrets and recriminations. Yusaku Matsuda was to adopt arguably his most famous role in 1979 – that of the unconventional private detective Shunsaku Kudo in the iconic television series Detective Story (unconnected with the film of the same name he made in 1983), but Murder in the Doll House (乱れからくり, Midare Karakuri) made the same year also sees him stepping into the shoes of a more conventional, literature inspired P.I.

Yusaku Matsuda was to adopt arguably his most famous role in 1979 – that of the unconventional private detective Shunsaku Kudo in the iconic television series Detective Story (unconnected with the film of the same name he made in 1983), but Murder in the Doll House (乱れからくり, Midare Karakuri) made the same year also sees him stepping into the shoes of a more conventional, literature inspired P.I. For 1970’s If You We’re Young: Rage (君が若者なら, Kimi ga Wakamono Nara), Fukasaku returns to his most prominent theme – disaffected youth and the lack of opportunities afforded to disadvantaged youngsters during the otherwise booming post-war era. Like the more realistic gangster epics that were to come, Fukasaku laments the generation who’ve been sold an unattainable dream – come to the city, work hard, make a decent life for yourself. Only what the young men find here is overwork, exploitation and a considerably decreased likelihood of being able to achieve all they’ve been promised.

For 1970’s If You We’re Young: Rage (君が若者なら, Kimi ga Wakamono Nara), Fukasaku returns to his most prominent theme – disaffected youth and the lack of opportunities afforded to disadvantaged youngsters during the otherwise booming post-war era. Like the more realistic gangster epics that were to come, Fukasaku laments the generation who’ve been sold an unattainable dream – come to the city, work hard, make a decent life for yourself. Only what the young men find here is overwork, exploitation and a considerably decreased likelihood of being able to achieve all they’ve been promised.