Japanese cinema is filled with tales of maternal self-sacrifice which is more often than not rejected by ungrateful children unable to understand the depths of a mother’s love. More contrarian than most would have it, Yasujiro Ozu’s abiding interest is with fathers and particularly with those who are flawed but loving. 1934’s A Story of Floating Weeds (浮草物語, Ukigusa Monogatari) which he later remade in colour 25 years later, is a tale of one such father and another of his “Kihachi” movies, but situates itself in a liminal space defined by Kihachi’s precarious position as a member of a virtual underclass of travelling players.

Kichachi’s (Takeshi Sakamoto) troupe is returning to a small town after four years where they hope to stay a year. Unbeknownst to the other members, Kihachi has an ulterior motive in that the town is home to his former lover Otsune (Choko Iida) and his illegitimate son, Shinkichi (Koji Mitsui) who thinks that Kichachi is just a family friend and that his father was a civil servant who has now passed away. As is usual in travelling player stories, the troupe is in crisis and on the verge of disbanding, so Kihachi’s frequent absences do not go unnoticed, particularly by his current mistress Otaka (Rieko Yagumo) who has a petty and vindictive streak. When one of the veteran actors spills the beans, she marches straight over to Otsune’s to make trouble but Kihachi, sick of her possessive behaviour, breaks up with her. To take revenge, she bribes another actress, Otoki (Yoshiko Tsubouchi), to seduce Shinkichi.

The central issue is one of Kihachi’s frustrated paternity. It’s clear that he couldn’t be physically present for his family but has always done his best to support them financially while Otsune runs a small restaurant. They are not married and their present relationship seems to be more one of companionship than romance but whatever label they might put on it they get along well and both deeply care for their son. While in town, Kihachi busies himself with fatherly activities, playing board games with Shinkichi or fishing in the local stream. It pains him that his visit may be short and that Shinkichi, who seems to like him a great deal, has no idea he is his son.

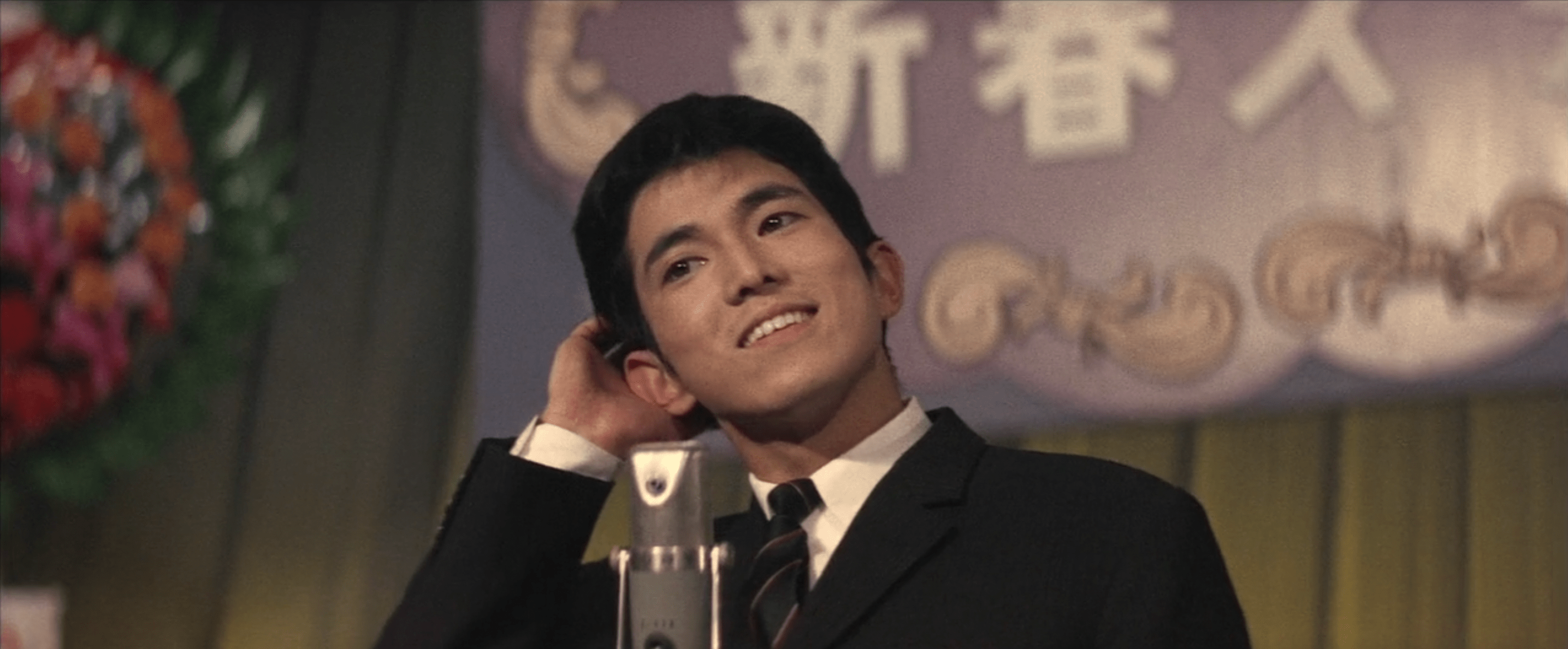

That is largely because Kihachi’s only hope in life is that he spare Shinkichi from the depressing life of a travelling player. He has been paying for his education and Shinkichi is now almost a man, apparently a post-graduate student at an agricultural school. When he expresses an interest in coming to see the show, Kihachi seems panicked and tells him the kinds of shows he does are not for people like him and that he should stay home and study. Shinkichi laughs at the fatherly advice but little knows that it comes from a place of shame. Travelling players are regarded as an underclass. They are often barred from inns and not considered polite company.

“My son belongs to a world better than yours,” he shouts to Otaka during a heated, rain-drenched argument during which she threatens to expose him. Otoki, the other actress, was originally reluctant to enact Otaka’s plan, but later found herself falling for Shinkichi. Perhaps a young man bedding a travelling actress isn’t a grand shame or much of a problem for him, at least not so much as to provoke Kichahi’s despair in exclaiming he has caused his son’s ruin, but destroys his father’s hopes of keeping him out of that untouchable world for which he had sacrificed so much including his paternal love.

Yet like the ungrateful child of a hahamono, on learning the truth Shinkichi rejects his sacrifice and feels only his abandonment, refusing to believe that any father could be so “selfish”. The rejection comes at a low point, immediately after Kihachi loses the acting troupe and considers returning to Otsune for a settled, ordinary life as a husband and father. Otsune scolds her son, reminding him that all he wanted was to give Shinkichi the settled, ordinary life that he could never live as a travelling player. It seems this life will always elude him, he is barred from his own home and must forever wander. Being a good father means he must keep far away from his son, a floating weed with no place to call home.