Busho Sawada’s serialised novel had been adapted several times before with the first released shortly after its publication in 1926, but this “modernised” version directed by Yasuzo Masumura, The Woman Who Touched Legs (足にさわった女, Ashi ni Sawatta Onna), is tailor-made for the post-war era as the titular woman heads off in search of the old Japan only to learn that it no longer exists and what little of it remains is being sold off for golf courses and ever expanding American airbases whose noisy aircraft fly constantly overhead.

To that extent, Saya (Machiko Kyo) is an embodiment of aimless post-war youth. Her father was accused of being a spy and took his own life while her mother worked herself to death when she was just a child. Though she travels with a rather dim young man who refers to her as his older sister, they are not actually related by blood and seem to have belonged to the same community of street criminals in Osaka along with their “big sister” Haruko (Haruko Sugimura) who has since moved back to Atsugi which is Saya’s “hometown”. Since her parents’ deaths, she’s been obsessed with the idea of revenge and pickpocketing money to save for a giant memorial service to show the relatives who chased her family out of town how well she’s done for herself. But when she arrives, she can’t even find the place she’s looking for. A policeman flips through a series of ancient, handwritten ledgers looking for evidence of people with her surname and suggests they’ve all left town. Even the last one left is the wife of an adopted son who plans to move to Tokyo after their house is purchased by developers who want to build a golf course.

The golf course may be a symbol of Japan’s increasing prosperity, but the airbases seem to hint more at a sense of corruption and oppression. Saya’s “hometown” is a mythical concept that belongs to an idealised vision of a pastoral Japan before the war that she unconsciously wants to return to. Her mother spoke of a small settlement of perhaps 30 houses, a village society with a river running through it. The village has now, however, been swallowed by the airbase and, in fact, erased so that no one even quite remembers it. Saya is left feeling that she no longer has a hometown, and ironically asks policeman Kita to arrest her so she can go back to prison, which is, perhaps, where her heart truly lies. At least, it’s much quieter than here without any noisy aircraft flying overhead.

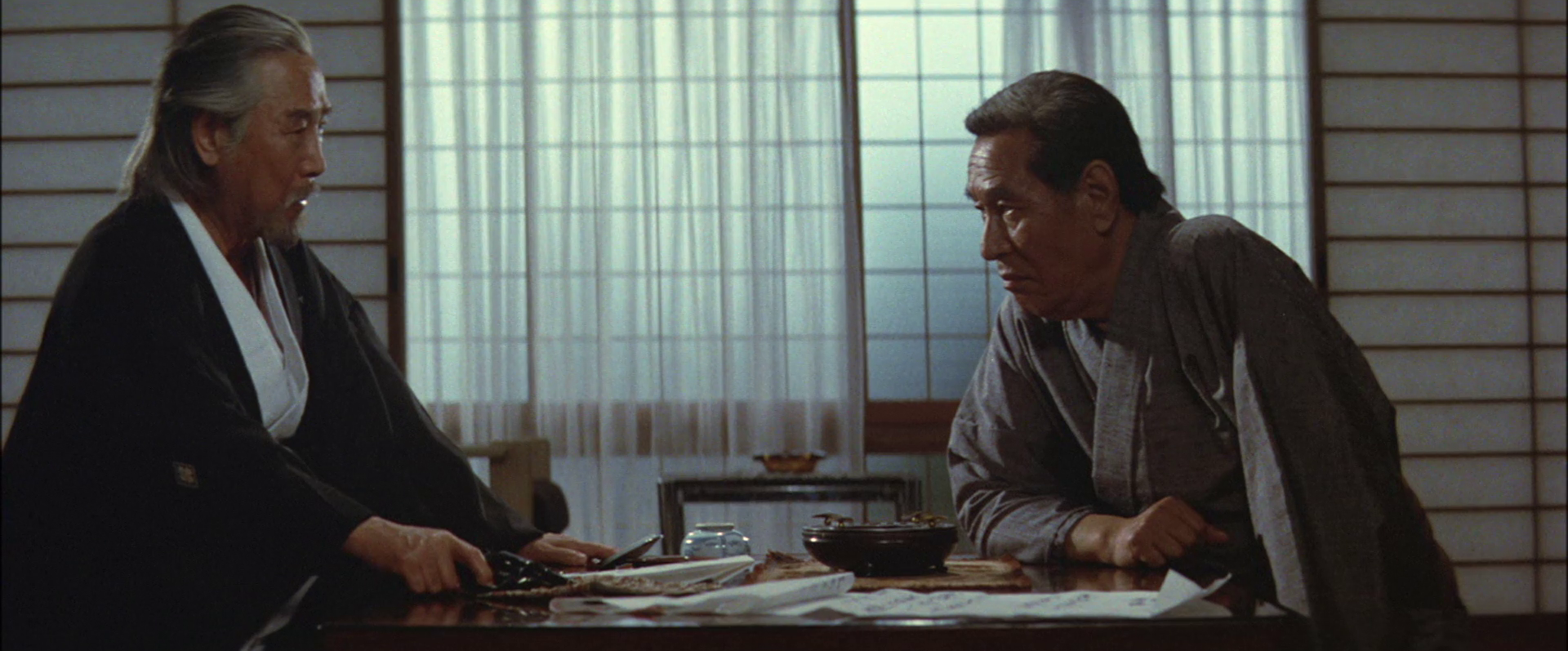

Nevertheless, Kita (Hajime Hana) is a fairly bumbling policeman and the film opens with what turns out to be part of a book set in a lawless Japan where people gamble, party, and openly sell guns on an ordinary train. Kita is currently on holiday, which he’s been forced to take even though he doesn’t really want to. He’s technically powerless for the moment, but continually complains that he’s not allowed to arrest Saya unless he catches her in the act of pickpocketing. It’s clear that the pair have feelings for each other it’s inconvenient to admit, and all this talk of “arrest” maybe more a kind of metaphor in which Saya secretly wants to be caught by Kita with the snapping of the handcuffs akin to the putting of a ring on a finger. The pair effectively lead each other on a merry dance with Saya ironically eventually chasing the policeman rather than the other way around.

The film does open rather salaciously with a closeup of a woman’s legs in fishnet tights followed by a kickline, and Machiko Kyo does indeed play up her sexy image to play the beautiful pickpocket who uses her body as a tool to mesmerise much to Haruko’s disapproval. Besides Kita, she’s followed by a rather louche writer (Eiji Funakoshi) who declares that he doesn’t need models, though evidently captivated by her, while declaring himself too successful and overworked. He doesn’t want more money, he just wants some free time and no one seems to want to let him have any, though he doesn’t exactly get a lot of writing done on this wild goose chase looking for Saya’s missing hometown. Absurd as it is, this unlikely rom-com between a beautiful pickpocket and bumbling policeman does at least end in a moment both of constraint and liberation as Saya finds herself content with her famous legs cuffed and Kita content to wear a different hat as they ride off on a decidedly unusual honeymoon.