Throughout his career Lee Sang-il has shown himself adept at creating ensemble character dramas but nowhere is this as much in evidence as in his well crafted debut, Border Line. Focussing on the unlikely overlapping stories of a number of people who each find themselves crossing a threshold of a more spiritual nature, Border Line traces back each of the fractures in contemporary society to the broken cord of the parental bond.

Throughout his career Lee Sang-il has shown himself adept at creating ensemble character dramas but nowhere is this as much in evidence as in his well crafted debut, Border Line. Focussing on the unlikely overlapping stories of a number of people who each find themselves crossing a threshold of a more spiritual nature, Border Line traces back each of the fractures in contemporary society to the broken cord of the parental bond.

We begin with teenage technical school student Matsuda (Sawaki Tetsu) who’s been in trouble for refusing to wear the required overalls. Later he runs away after his father is murdered only to be knocked down by drunken taxi driver Kurosawa (Murakami Jun) who ends up driving him half way to Hokkaido which is where he said he was from. Meanwhile, housewife Aikawa (Aso Yumi) has just started a new job at the combini but her son keeps skipping school and she soon realises it’s down to aggressive bullying. If that wasn’t enough, her husband has gone incommunicado after abruptly revealing via telephone that he lost his job a month ago and hasn’t found another one. Taking a step down to the underworld, we also meet low life gangster Miyaji (Mitsuishi Ken) who’s having a very bad as his partner ran off with the takings from a pachinko parlour to pay for expensive medical treatment for his daughter.

These are the lives of ordinary modern day people each facing extreme stress from all angles be they financial, societal, or existential. Matsuda is a young man and it’s only natural that he rebels a little to try and figure out who he is but it seems there may have been more going on in his life than just not wanting to wear a uniform. His mother left when he was a child and we don’t find out much about his relationship with his father but he spends the rest of the film looking for parental figures to essentially give him the permission to become an adult. The first of these is the taxi driver, Kurosawa, who, for various reasons isn’t able to help him (and only really decides he wanted to when it was too late). Finally, after a series of coincidences, he runs into Miyaji who is still grieving over having lost contact with his daughter after running out on his suicidal wife. Miyaji is not a great role model in many ways but still has some wisdom to impart to the younger man which may save his life in ways both literal and figural.

Miyaji and Aikawa are both coming from the other direction but struggling with their parental responsibilities. Aikawa has taken the job at the combini to help pay their mortgage – the house is very important to her as she was always ashamed of the modest home she grew up in with her parents. Like Miyaji, her husband seems to have more or less abandoned his family in his shame over losing his job, leaving Aikawa to bear all the responsibility for herself and her son. Eventually the pressure becomes so intense that Aikawa’s typical Japanese housewife persona starts to crumble resulting firstly in fantasies of violence before a crime filled rampage and kidnapping plot threaten to destroy what’s left of her life.

Back with the kids, another coincidence turns up Miyaji’s estranged high school aged daughter now also orphaned following the death of her mother leaving her with no other option than visiting hotel rooms with dodgy businessmen. Shunned at school and alone at home, hers is a lonely life marred by the failure of her parents. Both she and Matsuda, whom she eventually meets through another set of random coincidences, have had their futures ruined by poor parenting but, ironically, it maybe Miyaji who is able to help them even in his continued absence.

For a debut film, Border Line is a remarkably assured affair. Elegantly shot with decent production values, it handles its complicated set up with ease affording each of its distressed protagonists a degree of sympathy and understanding without the necessity of moral judgement. However, Lee does seem to want to lay the ills of modern society at the feet of the crumbling family unit only to present his younger protagonists with the idea of salvation as self actualisation. Decidedly low key, Lee’s debut film has a less commercial, deeper sensitivity than his subsequent efforts but still offers the compassionate sense of humanity which continues to inform his filmmaking.

Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the

Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the  I was 21 years when I wrote this song, I’m 22 now but I won’t be for long…the leaves that are green are turning to brown for the heroine of Keiko Desu Kedo (桂子ですけど, “I am Keiko”). Approaching her 22nd birthday and with the recent death of her father ever present in her mind, she’s begun to feel the passage of time even more keenly. She doesn’t want to miss out on or forget anything so she’s going to share with us the last three weeks of her 21st year on Earth.

I was 21 years when I wrote this song, I’m 22 now but I won’t be for long…the leaves that are green are turning to brown for the heroine of Keiko Desu Kedo (桂子ですけど, “I am Keiko”). Approaching her 22nd birthday and with the recent death of her father ever present in her mind, she’s begun to feel the passage of time even more keenly. She doesn’t want to miss out on or forget anything so she’s going to share with us the last three weeks of her 21st year on Earth. Koki Mitani is one of the most bankable mainstream directors in Japan though his work has rarely travelled outside of his native land. Beginning his career in the theatre, Mitani is the master of modern comedic farce and has the rare talent of being able to ground often absurd scenarios in the humour that is very much a part of everyday life. Welcome Back, Mr. McDonald (ラヂオの時間, Radio no Jikan) is Mitani’s debut feature in the director’s chair though he previously adapted his own stage plays as screenplays for other directors. This time he sets his scene in the high pressure environment of the production booth of a live radio drama broadcast as the debut script of a shy competition winner is about to get torn to bits by egotistical actors and marred by technical hitches.

Koki Mitani is one of the most bankable mainstream directors in Japan though his work has rarely travelled outside of his native land. Beginning his career in the theatre, Mitani is the master of modern comedic farce and has the rare talent of being able to ground often absurd scenarios in the humour that is very much a part of everyday life. Welcome Back, Mr. McDonald (ラヂオの時間, Radio no Jikan) is Mitani’s debut feature in the director’s chair though he previously adapted his own stage plays as screenplays for other directors. This time he sets his scene in the high pressure environment of the production booth of a live radio drama broadcast as the debut script of a shy competition winner is about to get torn to bits by egotistical actors and marred by technical hitches. Hiroko Yakushimaru was one of the biggest idols of the 1980s. After starring in Shinji Somai’s

Hiroko Yakushimaru was one of the biggest idols of the 1980s. After starring in Shinji Somai’s  Yoshimitsu Morita, though committed to commercial filmmaking, also enjoyed trying on different kinds of directorial hats from from purveyor of smart social satires to teen idol movies, high art literary adaptations and just about everything else in-between. It’s no surprise then that at the height of the J-horror boom, he too got in on the action with an adaptation of Yusuke Kishi’s novel of the same name, The Black House (黒い家, Kuroi Ie). Though tagged as “J-horror” you’ll find no long haired ghosts here and, in fact, barely anything supernatural as the true horror on show is the slow descent into madness taking place inside the protagonist’s mind.

Yoshimitsu Morita, though committed to commercial filmmaking, also enjoyed trying on different kinds of directorial hats from from purveyor of smart social satires to teen idol movies, high art literary adaptations and just about everything else in-between. It’s no surprise then that at the height of the J-horror boom, he too got in on the action with an adaptation of Yusuke Kishi’s novel of the same name, The Black House (黒い家, Kuroi Ie). Though tagged as “J-horror” you’ll find no long haired ghosts here and, in fact, barely anything supernatural as the true horror on show is the slow descent into madness taking place inside the protagonist’s mind. In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be.

In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be. You wouldn’t think it wise but apparently some people are so trusting that they don’t think twice about recording a new answerphone message to let potential callers know that they’ll be away for a while. On the face of things, they’re lucky that the guy who’ll be making use of this valuable information is a young drifter without a place of his own who’s willing to pay his keep by doing some household chores or fixing that random thing that’s been broken for ages but you never get round to seeing to. So what if he likes to take a selfie with your family photos before he goes, he left the place nicer than he found it and you probably won’t even know he was there.

You wouldn’t think it wise but apparently some people are so trusting that they don’t think twice about recording a new answerphone message to let potential callers know that they’ll be away for a while. On the face of things, they’re lucky that the guy who’ll be making use of this valuable information is a young drifter without a place of his own who’s willing to pay his keep by doing some household chores or fixing that random thing that’s been broken for ages but you never get round to seeing to. So what if he likes to take a selfie with your family photos before he goes, he left the place nicer than he found it and you probably won’t even know he was there.

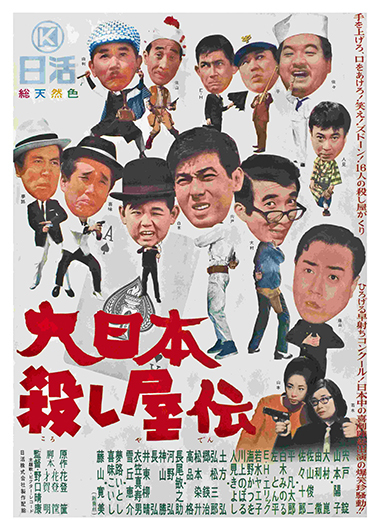

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.