It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth.

It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth.

Fuji (Mitsugu Fujii) is the star of the university rugby team. In fact his prowess on the rugby field has made him something of a mini celebrity and a big man on campus which Fuji seems to enjoy very much. At home, he’s the son of a successful soy sauce brewer with distinctly conservative attitudes. Fuji’s father has just married off one of his daughters to an employee and is setting about sorting out the second one despite the reluctance of all parties involved. Everyone seems very intent on Fuji also hurrying up with finishing his studies so he can conform to the normal social rules by working hard and getting married.

Fuji, however, spends most of his off the pitch time drinking with geisha, one of whom has unwisely fallen in love with him. Like many teams, Fuji’s rugby buddies have a strict “orderly conduct” rule which Fuji has been breaking thanks to his loose ways. His top player status has kept him safe but also made him enemies and when an embarrassing incident proves too much to overlook he’s finally kicked off the team.

The times may have been changing, but Fuji’s soy sauce shop remains untouched. Gohei (Haruro Takeda), the patriarch, grumpily rules over all with a “father knows best” attitude, refusing to listen to his son’s complaints. In fact, he tries to bypass his son altogether by marrying off another employee to his younger daughter, Miyako. Though Miyako tries to come to the employee’s defence (as well as her own) by informing her father that “this way of treating employees is obsolete”, she is shrugged off by Gohei’s authoritarian attitude. He’s already tried this once by arranging a marriage for his older daughter but his son-in-law spends all his time in geisha houses, often accompanied by Fuji, and the match has produced neither a happy family nor a successful business arrangement.

Fuji is a young man and he wants to enjoy his youth, in part because he knows it will be short and that conformity is all that awaits him. His dalliance with a geisha which contributes to him being kicked off the rugby team is in no way serious on his part (caddish, if not usually so). However, when he befriends an injured teammate and meets his showgirl sister, Fuji falls in love for real. This presents a problem for the friend whose main commitment is to the rugby team who were thinking of reinstating Fuji because they have a big match coming up and need him to have any chance of not disgracing themselves. This poor woman who has apparently been forced onto the stage to pay her brother’s school fees is then physically beaten by him (if in a childishly brotherly way) until she agrees to break things off with Fuji for the good of the rugby team.

Fuji is finally allowed onto the pitch again, in part at the behest of his previously hostile father who thinks rugby training is probably better than spending all night drinking (and keeping his brother-in-law out all night with him). The loss of status Fuji experienced after leaving the team rocked him to the core though his central conflict goes back to his place as his father’s son. At one point, Fuji argues with a friend only for a woman to emerge and inform him that his friend had things he longed to tell him, but he could never say them to “the young master”. Fuji may have embraced his star label, but he doesn’t want this one of inherited burdens and artificial walls. Hard as he tries, he can never be anything other than “the boss’ son”, with all of the pressures and responsibilities that entails but with few of the benefits. Getting back on the team is, ironically, like getting his individual personality back but also requires sacrificing it for the common good.

In contrast with some of Shimizu’s post-war films which praise the importance of working together for a common good but imply that the duty of the individual is oppose the majority if it thinks it’s wrong, here Fuji is made to sacrifice everything in service of the team. At the end of his final match, Fuji remarks to his teammate that this is “the end of their beautiful youth”. After graduation, they’ll find jobs, get married, have children and lose all rights to any kind of individual expression. Fuji is still torn between his “selfish” hedonistic desires and the growing responsibilities of adulthood, but even such vacillation will soon be unavailable to him. Ending on a far less hopeful note than many a Shimizu film with Fuji silently crying whilst his teammates celebrate victory, The Boss’ Son Goes to College is a lament for the necessary death of the self as a young man contemplates his impending graduation into the adult world, but it’s one filled with a rosy kind of humour and an unwilling resignation to the natural order of things.

Ohara Shousuke-san (小原庄助さん) is the name of a character from a popular folk song intended to teach children how not to live their lives. The Ohara Shosuke-san of Aizu Bandaisan has lost all his fortune but no one feels very sorry for him because it’s his own fault – he spent his days in idleness, drinking, sleeping in, and bathing in the morning. The central character of Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 film has earned this nickname for himself because he also enjoys a drink or too and doesn’t actually do very much else, but unlike the character in the song this a goodhearted man much loved by the community because he’s a soft touch and just can’t refuse when asked for a favour. An acknowledgement of the changing times, Shimizu’s Mr. Shousuke Ohara is a tribute to the soft hearted but also an argument for action over passivity.

Ohara Shousuke-san (小原庄助さん) is the name of a character from a popular folk song intended to teach children how not to live their lives. The Ohara Shosuke-san of Aizu Bandaisan has lost all his fortune but no one feels very sorry for him because it’s his own fault – he spent his days in idleness, drinking, sleeping in, and bathing in the morning. The central character of Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 film has earned this nickname for himself because he also enjoys a drink or too and doesn’t actually do very much else, but unlike the character in the song this a goodhearted man much loved by the community because he’s a soft touch and just can’t refuse when asked for a favour. An acknowledgement of the changing times, Shimizu’s Mr. Shousuke Ohara is a tribute to the soft hearted but also an argument for action over passivity. Johnnie To is best known as a purveyor of intricately plotted gangster thrillers in which tough guys outsmart and then later outshoot each other. However, To is a veritable Jack of all trades when it comes to genre and has tackled just about everything from action packed crime stories to frothy romantic comedies and even a musical. This time he’s back in world of the medical drama as an improbable farce develops driven by the three central cogs who precede to drive this particular crazy train all the way to its final destination.

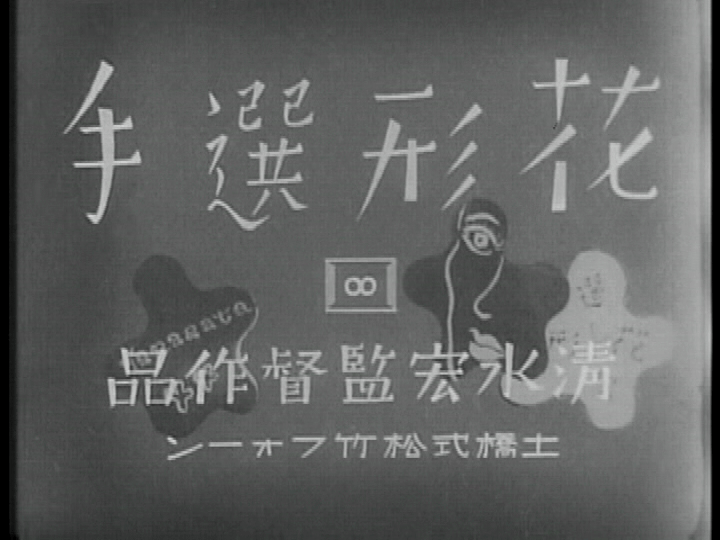

Johnnie To is best known as a purveyor of intricately plotted gangster thrillers in which tough guys outsmart and then later outshoot each other. However, To is a veritable Jack of all trades when it comes to genre and has tackled just about everything from action packed crime stories to frothy romantic comedies and even a musical. This time he’s back in world of the medical drama as an improbable farce develops driven by the three central cogs who precede to drive this particular crazy train all the way to its final destination. Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind.

Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind. Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance.

Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance. Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all.

Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all. Those golden last few summers of high school have provided ample material for countless nostalgia filled Japanese comedies and 700 Days of Battle: Us vs. the Police (ぼくたちと駐在さんの700日戦争, Bokutachi to Chuzai-san no 700 Nichi Senso) is no exception. Set in a small rural town in 1979, this is an innocent story of bored teenagers letting off steam in an age before mass communications ruined everyone’s fun.

Those golden last few summers of high school have provided ample material for countless nostalgia filled Japanese comedies and 700 Days of Battle: Us vs. the Police (ぼくたちと駐在さんの700日戦争, Bokutachi to Chuzai-san no 700 Nichi Senso) is no exception. Set in a small rural town in 1979, this is an innocent story of bored teenagers letting off steam in an age before mass communications ruined everyone’s fun. It’s become almost a cliché to describe a sequel as “unnecessary”, but then assessing how any sequel or, indeed, any film might be deemed “necessary” (for what or whom?) proves more fraught than one might originally think. It might, then, be better to think of certain sequels as “unwise” – S Storm (S風暴), a followup to the similarly named Z Storm is just one such film. Z Storm’s critical reception was, shall we say, lukewarm and did not exactly inspire a burning desire to return to its world of corporate corruption vs different kinds of bickering policemen but, nevertheless, here we are.

It’s become almost a cliché to describe a sequel as “unnecessary”, but then assessing how any sequel or, indeed, any film might be deemed “necessary” (for what or whom?) proves more fraught than one might originally think. It might, then, be better to think of certain sequels as “unwise” – S Storm (S風暴), a followup to the similarly named Z Storm is just one such film. Z Storm’s critical reception was, shall we say, lukewarm and did not exactly inspire a burning desire to return to its world of corporate corruption vs different kinds of bickering policemen but, nevertheless, here we are. Cities are often serendipitous places, prone to improbable coincidences no matter how large or densely populated they may be. Tokyo Serendipity (恋するマドリ, Koisuru Madori) takes this quality of its stereotypically “quirky” city to the limit as a young art student finds herself caught up in other people’s unfulfilled romance only to fall straight into the same trap herself. Its tale may be an unlikely one, but director Akiko Ohku neatly subverts genre norms whilst resolutely sticking to a mid-2000s indie movie blueprint.

Cities are often serendipitous places, prone to improbable coincidences no matter how large or densely populated they may be. Tokyo Serendipity (恋するマドリ, Koisuru Madori) takes this quality of its stereotypically “quirky” city to the limit as a young art student finds herself caught up in other people’s unfulfilled romance only to fall straight into the same trap herself. Its tale may be an unlikely one, but director Akiko Ohku neatly subverts genre norms whilst resolutely sticking to a mid-2000s indie movie blueprint. Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own.

Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own.