A pure hearted doctor stands strong against the forces of imperialism if somewhat ambivalently in Kiyoshi Saeki’s wartime drama The Sand City in Manchuria (砂漠を渡る太陽, Sabaku wo Wataru Taiyo). “Why isn’t there just one country? I don’t want a country” a young Chinese woman exclaims towards the film’s conclusion in what is intended as an anti-war statement but also invites the inference that the one country should be Japan and that China is wrong to resist the kind of “co-existence” that the idealistic hero is fond of preaching.

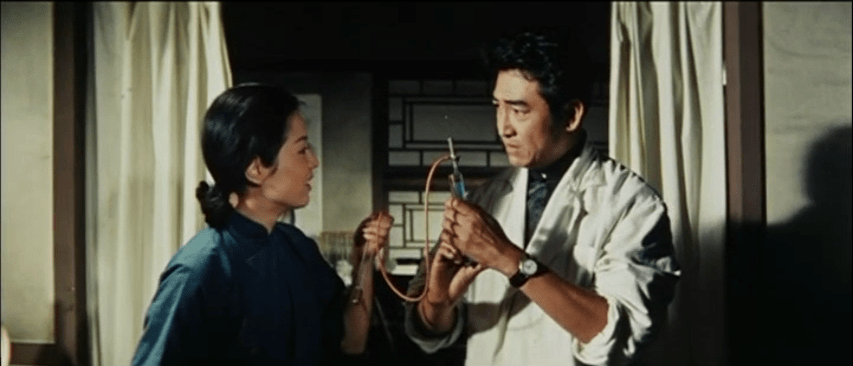

Dr. Soda (Koji Tsuruta), known as Soh, has been in Manchuria for two years running a poor clinic in a trading outpost on a smuggling route through the desert. He came, he later tells another Japanese transplant, after being talked into it by a pastor who told him about US missionaries who endured hardship in the Gobi desert and lamented that no Japanese people had been willing to take on such “thankless” work in the midst of the imperial expansion. There is a kind of awkwardness in Soda’s positioning as the good Japanese doctor which perhaps reflects the view from 1960 in that he objects to the way the Japanese military operates in Manchuria and most particularly to Japanese exceptionalism which causes them to look down on the local Chinese community as lesser beings, but within that all he preaches is equality and co-existence which suggests that he sees nothing particularly wrong in Japan being in Manchuria in the first place while implying that the Chinese are expected to simply co-exist with an occupying force to which they have in any case been given no choice but to consent.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that the Japanese are in this case the bad guys. Soda is at one point accosted by a drunken soldier who takes against his choice to adopt Chinese dress while rudely refusing to pay his rickshaw driver. The animosity of some in the town is well justified as we hear that their mother was murdered by a Japanese soldier, or that they were raped by Japanese troops and now have nothing but hate for them to they extent that they would withhold vital medical treatment from a child rather than consider allowing Soda to treat them. Soda’s main paying job is working at an opium clinic hinting at the various ways imperialist powers have used the opium trade to bolster their control over the local population, while it later becomes clear that one of the Chinese doctors has been in cahoots with a corrupt Japanese intelligence officer to, ironically, syphon off opium meant for medical uses and sell it to addicts in a truly diabolical business plan.

Though Soda is well respected in the town because he offers free medical treatment to those who could never otherwise afford it, he is sometimes naive about their real living conditions. Outraged that a young woman has been sold into sexual slavery, he marches off to the red light district to buy her back but is confused on his return realising her family aren’t all that happy about it because they cannot afford to feed her and were depending on the money she would send them because the father has become addicted to opium and can no longer work. The girl, Hoa (Yoshiko Sakuma), becomes somewhat attached to Soda but he is largely uninterested in her because she is only 17, while her affection for him causes tension with the daughter of an exiled Russian professor which is only repaired once they all start working together for the common good after the town after it comes under threat from infectious disease.

In an echo of our present times, it seems not much has changed in the last 80 years or so, the townspeople quickly turn on Soda once it become clear that he’s putting the town on lockdown to prevent the spread of infectious meningitis after a Russian soldier stumbles in and dies of it. The disease firstly exposes the essential racism even among those Japanese people who have lived in Manchuria longterm such as the mysterious Ishida (So Yamamura) who remarks that diseases like that only affect the Manchurians and they’ll be fine because they are “more hygienic”, while simultaneously painting the infection as a symptom of foreign corruption delivered by the Russian incursion. Soda visits a larger hospital to get the samples confirmed but is told that the disease has not been seen in Manchuria before and so they have no vaccine stocks leaving him dependent on the smuggling network to get the supplies he needs. As the town is a trading outpost whose entire economy is dependent on the business of travellers just passing through, the townspeople are obviously opposed to the idea of keeping them out fearing that they will soon starve going so far as to tear down Soda’s quarantine signs while throwing stones at his house.

In another irony, it’s Ishida’s pistol that wields ultimate control immediately silencing the mayor’s objections in a rude reminder of the local hierarchy. Many of the townspeople including inn owner Huang (Yunosuke Ito) and Hoa’s sister Shari (Naoko Kubo) are involved with the resistance to which Soda seems to remain quite oblivious and in any case adopts something of a neutral position but gains a grudging respect from Huang thanks to his humanitarianism that eventually saves him from brutal bandit Riyan (a rare villain role for a young Ken Takakura). In any case, as the corrupt Japanese officials pull out to escape the imminent Russian incursion, Soda decides to stay in part to atone for the sins of the Japanese in an acceptance of his responsibility as a Japanese person if one who has not (directly) participated in the imperialist project even if he was in a sense still underpinning it. Essentially a repurposed ninkyo eiga starring Koji Tsuruta as a morally upright man surrounded by corruption but trying to do the right thing to protect those who cannot protect themselves, there is an undeniable awkwardness in the film’s imperialist ambivalence but also a well intentioned desire to look back at the wartime past with clearer eyes and a humanitarian spirit.