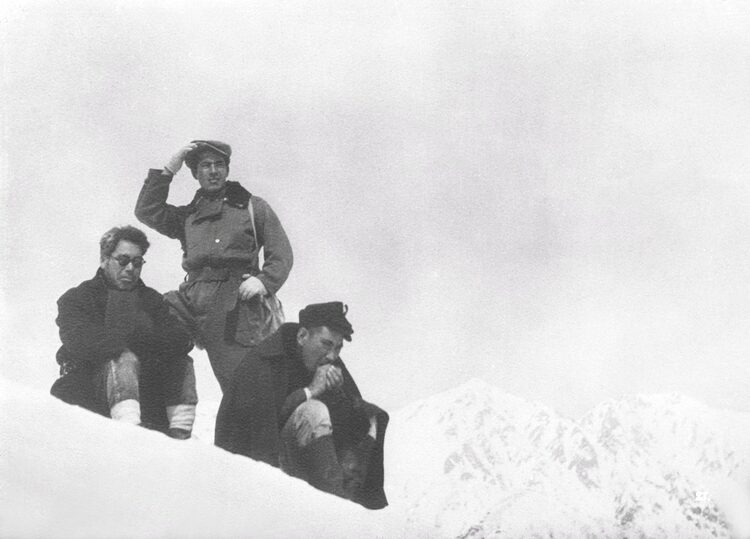

The cinema of the immediate post-war era might in a sense be aspirational, but it rarely shies away from hardship or from the sometimes difficult choices which had to be made both in terms of individual survival and the future direction of a society. Remembered chiefly for featuring the debut of screen legend Toshiro Mifune, Senkichi Taniguchi’s Snow Trail (銀嶺の果て, Ginrei no Hate) is less a crime doesn’t pay story than it is an affirmation that it’s never too late to turn back and that people who do “bad” things aren’t always “bad”, only troubled and desperate, but can be guided back towards the right path by the power of simple human goodness.

As the film opens, a trio of thieves commits a daring bank robbery and then heads off on the run intending to hideout in the mountains posing as tourists on a skiing trip. To facilitate their ruse, they’ve cut off communication by fiddling with radios and disabling telephones but two young men with too much time on their hands have already heard about the robbery and figured out the three suspicious gentlemen might be the fugitive criminals. In another picture, the two young guys would be the bumbling heroes, mistaken in their assumption that their world has been invaded by crime and probably finding romantic disappointment before heading home. This time however their guess is correct and their investigation has placed them in danger. The leader, Nojiri (Takashi Shimura), whips out a gun on a collection of drunken labourers and forces them out of their clothes and into the hot spring so the gang can make their escape further up the mountain, eventually taking refuge in a tiny lodge run by a philosophical grandpa (Kokuten Kōdo) and his cheerful teenage granddaughter (Setsuko Wakayama).

The police are in hot pursuit, but it is by nature which we will be judged. After leaving the hotel, the trio stop briefly in a ranger’s hut where hotheaded youngster Eijima (Toshiro Mifune) suggests splitting up. Nojiri divides the loot, giving each their promised share, but the other guy, Takasugi (Yoshio Kosugi), objects. He doesn’t want to go it alone and resents being forced to make his own way, even wondering out loud how long they’d get if they gave themselves up now. After a fight knocks Takasugi out, Eijima is keen to leave him behind, but he ends up spelling his own doom when he fires his gun at the police and provokes an avalanche.

Later the patient grandfather tells us that the “mighty mountain punishes the bad”, and Takasugi is presumably its first victim, paying the price for panic and cowardice. Meanwhile, Nojiri and Eijima find themselves playing tourists once again in the mountain lodge where Nojiri is touched by the simple innocence of the young girl and her grandfather and Eijima paces around impatiently like a caged animal, cruelly killing the little girl’s prized carrier pigeon in case it takes it upon itself to signal the authorities. Threatening the girl’s life, Eijima convinces another guest, Honda (Akitake Kono), to guide them safely over the mountains to escape, but becomes increasingly paranoid that he will be betrayed, knowing he does not have the skills to survive alone in this environment.

Nojiri meanwhile is drawn back towards humanity. Already softened by Harue, the cheerful young woman at the lodge who innocently offers him honey tea and reminds him of his own daughter who passed away at a similar age, he remains conflicted in their coercion of Honda and even more chastened after Honda saves both of their lives when Nojiri slips breaking own his arm in the process. Later, Nojiri asks him why he helped them rather than just cutting the rope and escaping. He replies that all he did was respect the code of the mountains. “The rope that ties one life to another must never be touched” he tells him.

In an unexpected twist, Nojiri’s humanity is reawakened by a song filled with nostalgia but it isn’t Furusato or Akatombo, it’s “My Old Kentucky Home” played in an instrumental version on Harue’s portable record player, previously used by Honda who performed a silly dance to tune of Oh Suzannah. The choice of music perhaps echoes the movie’s Hollywood inspiration, but otherwise follows the pattern of other similarly themed contemporary crime movies in which the hero is eventually redeemed by connecting with his own childhood innocence through the “furusato” spirit. Still able to find this essential goodness within himself, the mountain has judged Nojiri favourably, proving that as grandpa says he isn’t a “bad” person even if he’s made “bad” choices. Filled with a new respect for the ropes that bind one human to another, he is allowed to return to the world presumably to live a more connected existence cheerfully helping others rather than remaining selfishly alone.