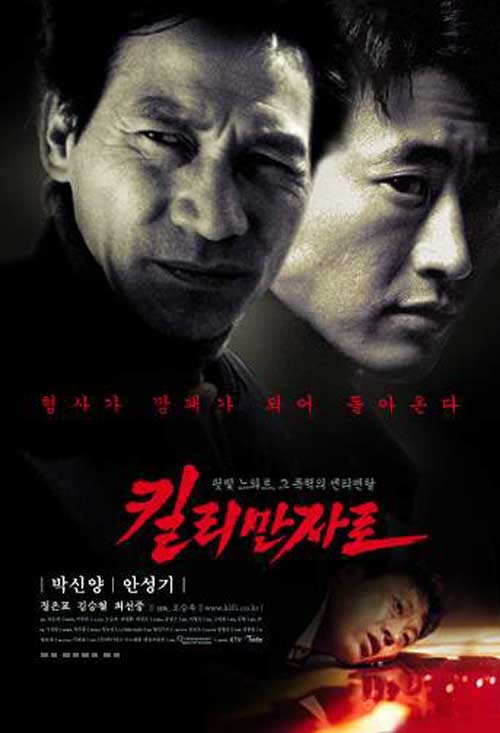

Mt. Kilimanjaro is the world’s tallest free-standing mountain. Oh Seung-ok’s debut, Kilimanjaro (킬리만자로), is not a climbing story, at least not in that sense, but a story of a man trying to conquer his own mountain without really knowing why. Twin brothers Hae-shik and Hae-chul are mirrors of each other, a perfect mix of light and dark, but when one makes a choice to choose the darkness, it throws the other into despair and confusion. A noir-ish tale of fragmented identities and fatalistic retribution, Oh’s world of tired gangsters and impossible dreams is as icy and unforgiving as the summit of its titular mountain, offering little more than lonely deaths and eternal regrets.

Mt. Kilimanjaro is the world’s tallest free-standing mountain. Oh Seung-ok’s debut, Kilimanjaro (킬리만자로), is not a climbing story, at least not in that sense, but a story of a man trying to conquer his own mountain without really knowing why. Twin brothers Hae-shik and Hae-chul are mirrors of each other, a perfect mix of light and dark, but when one makes a choice to choose the darkness, it throws the other into despair and confusion. A noir-ish tale of fragmented identities and fatalistic retribution, Oh’s world of tired gangsters and impossible dreams is as icy and unforgiving as the summit of its titular mountain, offering little more than lonely deaths and eternal regrets.

Policeman Hae-shik (Park Shin-Yang) drifts in and out of consciousness, tied up in a room by his twin brother, Hae-chul, with Hae-chul’s children looking on. Hae-chul murders his family and then shoots himself all while his brother is tied up and helpless, a policeman without recourse to the law. Taken to task by his colleagues who want to know how he could have allowed any of this to happen, if not as a brother than as a cop, Hae-shik has little to offer them by way of explanation. To add insult to injury, he is also under fire for unethical/incompetent investigation, and is taken off the case. Suspended pending an inquiry, Hae-shik goes back to his hometown but is immediately mistaken for Hae-chul and attacked by gangsters Hae-chul had pissed off before he left town and killed himself. Saved by local petty gangster Thunder (Ahn Sung-Ki), Hae-shik assumes Hae-chul’s identity and slips into the life of hopeless scheming which ultimately led to his brother’s ugly, violent death.

The film’s title is, apparently, slightly ironic in referring to the film’s setting of a small fishing village in the mountainous Gangwon-do Providence, known to some as “Korea’s Kilimanjaro”. Each of the men in this small town is trapped by its ongoing inertia and continual impossibility. They want to make something of themselves but have few outlets to do so – their dream is small, owning a family restaurant, but still it eludes them and they soon turn to desperate measures in opposing a local gangster in the hope of finally improving their circumstances.

Despite the seemingly tight bond of the men in Thunder’s mini gang – a mentally scarred ex-soldier known as “The Sergeant” (Jung Eun-pyo) and nerdy religious enthusiast knows as “The Evangelical” (Choi Seon-jung) rounding out Hae-chul’s goodhearted chancer, none of them has any clue that Hae-shik is not Hae-chul, or that Hae-chul and his family are dead. No one, except perhaps Thunder, is very happy to see him but even so Hae-shik quickly “reassumes” his place at Thunder’s side and takes over Hae-chul’s role in the gang’s scheming.

Hae-shik and Hae-chul had formed a perfect whole of contradictory qualities, each with their own degrees of light and darkness. Hae-chul had been the “good” brother who worked hard at home taking care of his parents while Hae-shik headed to university and a career in the city, never having visited his hometown since (in fact, no one seems to know or has already forgotten that Hae-chul even had a twin brother). Hae-shik’s “goodness” might be observed in his career as a law enforcer, but he’s clearly not among the list of model officers, and his home life also seems to be a failure. Hae-chul’s family might also have failed, and his shift to a life of petty crime provides its own darkness but living in this claustrophobic, impossible environment his crime is one of wanting something more than that his world ever had to offer him.

As might be expected, Thunder’s plans do not unfold as smoothly as hoped. Ineptitude and finally a mental implosion result in a near massacre costing innocent lives taken in a fury of misdirected vengeance. Despite wishing for a quiet life spent with friends on the beach, heroes die all alone, like mountain climbers lost on a snowy slope unsure whether to go up or down. Attempting to integrate his contradictions, become his brother as well as himself, Hae-shik reaches an impasse that is pure noir, finally meeting his end through a case of “mistaken identity”.

Screened at London Korean Film Festival 2017.

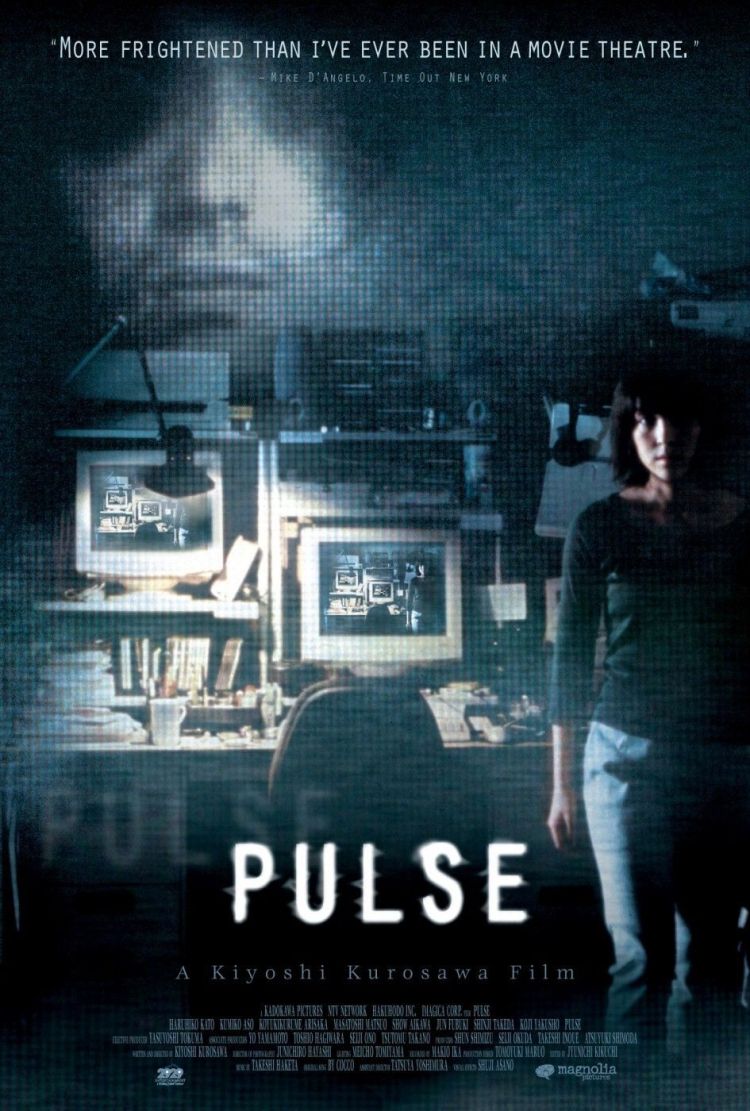

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence.

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence. In the closing voice over of Banmei Takahashi’s Rain of Light (光の雨, Hikari no Ame), the elderly narrator thanks us, the younger generation, for listening to this long, sad story. The death of the leftist movement in Japan has never been a subject far from Japanese screens whether from contemporary laments for a perceived failure as the still young protestors swapped revolution for the rat race or a more recent and rigorous desire to examine why it all ended in such a dark place. Rain of Light is an attempt to look at the Asama-Sanso Incident through the eyes of the youth of today and by implication ask a few hard questions about the nature of revolution and social change and if either of those two things have any place in the Japan these young people now live in. Takahashi reframes the tale as docudrama in which his young actors and actresses, along with their increasingly conflicted director, attempt to solve these problems through recreation and role play, bridging the gap between the generations with a warning from those who dreamed of a better world that was never to be.

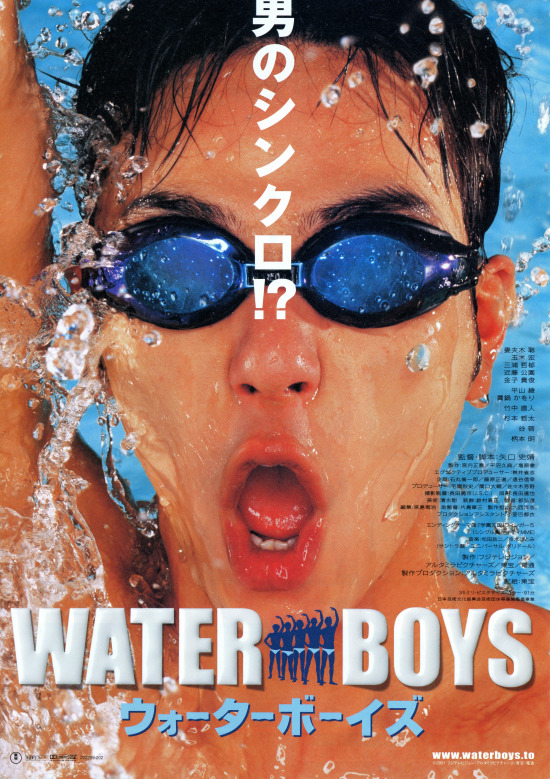

In the closing voice over of Banmei Takahashi’s Rain of Light (光の雨, Hikari no Ame), the elderly narrator thanks us, the younger generation, for listening to this long, sad story. The death of the leftist movement in Japan has never been a subject far from Japanese screens whether from contemporary laments for a perceived failure as the still young protestors swapped revolution for the rat race or a more recent and rigorous desire to examine why it all ended in such a dark place. Rain of Light is an attempt to look at the Asama-Sanso Incident through the eyes of the youth of today and by implication ask a few hard questions about the nature of revolution and social change and if either of those two things have any place in the Japan these young people now live in. Takahashi reframes the tale as docudrama in which his young actors and actresses, along with their increasingly conflicted director, attempt to solve these problems through recreation and role play, bridging the gap between the generations with a warning from those who dreamed of a better world that was never to be. Japan has really taken the underdog triumphs genre of sports comedy to its heart but there can be few better examples than Shinobu Yaguchi’s 2001 teenage boys x synchronised swimming drama Waterboys (ウォーターボーイズ). Where the conventional sports movie may rely on the idea of individual triumph(s), Waterboys, like many similarly themed Japanese movies, has group unity at its core as our group of disparate and previously downtrodden high school boys must find their common rhythm in order to truly be themselves. Setting high school antics to one side and attempting to subvert the normal formula as much as possible, Yaguchi presents a celebration of acceptance and assimilation as difference is never elided but allowed to add to a growing harmony as the boys discover all new sides of themselves in their quest for water borne success.

Japan has really taken the underdog triumphs genre of sports comedy to its heart but there can be few better examples than Shinobu Yaguchi’s 2001 teenage boys x synchronised swimming drama Waterboys (ウォーターボーイズ). Where the conventional sports movie may rely on the idea of individual triumph(s), Waterboys, like many similarly themed Japanese movies, has group unity at its core as our group of disparate and previously downtrodden high school boys must find their common rhythm in order to truly be themselves. Setting high school antics to one side and attempting to subvert the normal formula as much as possible, Yaguchi presents a celebration of acceptance and assimilation as difference is never elided but allowed to add to a growing harmony as the boys discover all new sides of themselves in their quest for water borne success. Lav Diaz’s auteurist break through, Batang West Side is among his more accessible efforts despite its daunting (if “concise” by later standards) five hour running time. Ostensibly moving away from the director’s beloved Philippines, this noir inflected tale apes a police procedural as New Jersey based Filipino cop Mijares (Joel Torre) investigates the murder of a young countryman but is forced to face his own darkness in the process. Diaspora, homeland and nationhood fight it out among those who’ve sought brighter futures overseas but for this collection of young Filipinos abroad all they’ve found is more of home, pursued by ghosts which can never be outrun. These young people muse on ways to save the Philippines even as they’ve seemingly abandoned it but for the central pair of lost souls at its centre, a young one and an old one, abandonment is the wound which can never be healed.

Lav Diaz’s auteurist break through, Batang West Side is among his more accessible efforts despite its daunting (if “concise” by later standards) five hour running time. Ostensibly moving away from the director’s beloved Philippines, this noir inflected tale apes a police procedural as New Jersey based Filipino cop Mijares (Joel Torre) investigates the murder of a young countryman but is forced to face his own darkness in the process. Diaspora, homeland and nationhood fight it out among those who’ve sought brighter futures overseas but for this collection of young Filipinos abroad all they’ve found is more of home, pursued by ghosts which can never be outrun. These young people muse on ways to save the Philippines even as they’ve seemingly abandoned it but for the central pair of lost souls at its centre, a young one and an old one, abandonment is the wound which can never be healed. Tony Leung Chiu-wai may have just won a best actor prize in Cannes, but that didn’t stop him getting right back on the HK treadmill with the run of the mill rom-com, Fighting for Love (同居蜜友). Reuniting director Jack Ma with Feel 100% star Sammi Cheng, Fighting for Love is the kind of wacky, thrown together romantic comedy that no one really makes any more (not that that’s altogether a bad thing). Still, even if the film is over reliant on its two leads to overcome the overabundance of subplots, it also makes use of their sparky chemistry to keep things moving along.

Tony Leung Chiu-wai may have just won a best actor prize in Cannes, but that didn’t stop him getting right back on the HK treadmill with the run of the mill rom-com, Fighting for Love (同居蜜友). Reuniting director Jack Ma with Feel 100% star Sammi Cheng, Fighting for Love is the kind of wacky, thrown together romantic comedy that no one really makes any more (not that that’s altogether a bad thing). Still, even if the film is over reliant on its two leads to overcome the overabundance of subplots, it also makes use of their sparky chemistry to keep things moving along. The time after high school is often destabilising as even once close groups of friends find themselves being pulled in all kinds of different directions. So it is for the group of five young women at the centre of Jeong Jae-eun’s debut feature, Take Care of My Cat (고양이를 부탁해, Goyangileul Butaghae). All at or around 20, the age of majority in Korea, the girls were a tightly banded unit during high school but have all sought different paths on leaving. Lynchpin Tae-hee (Bae Doo-na) is responsible for trying to keep the gang together through organising regular meet ups but it’s getting harder to get everyone in the same place and minor differences which hardly mattered during school grow ever wider as adulthood sets in.

The time after high school is often destabilising as even once close groups of friends find themselves being pulled in all kinds of different directions. So it is for the group of five young women at the centre of Jeong Jae-eun’s debut feature, Take Care of My Cat (고양이를 부탁해, Goyangileul Butaghae). All at or around 20, the age of majority in Korea, the girls were a tightly banded unit during high school but have all sought different paths on leaving. Lynchpin Tae-hee (Bae Doo-na) is responsible for trying to keep the gang together through organising regular meet ups but it’s getting harder to get everyone in the same place and minor differences which hardly mattered during school grow ever wider as adulthood sets in. The family drama is a mainstay of Japanese cinema, true, but, it’s a far wider genre than might be assumed. The rays fracture out from Ozu through to

The family drama is a mainstay of Japanese cinema, true, but, it’s a far wider genre than might be assumed. The rays fracture out from Ozu through to  Sometimes God’s comic timing is impeccable. You might hear it said that love transcends death, becomes an eternal force all of its own, but the “love story”, if you can call it that, of the two characters at the centre of Song Hae-sung’s Failan (파이란, Pairan), who, by the way, never actually meet, occurs entirely in the wrong order. It’s one thing to fall in love in a whirlwind only to have that love cruelly snatched away by death what feels like only moments later, but to fall in love with a woman already dead? Fate can be a cruel master.

Sometimes God’s comic timing is impeccable. You might hear it said that love transcends death, becomes an eternal force all of its own, but the “love story”, if you can call it that, of the two characters at the centre of Song Hae-sung’s Failan (파이란, Pairan), who, by the way, never actually meet, occurs entirely in the wrong order. It’s one thing to fall in love in a whirlwind only to have that love cruelly snatched away by death what feels like only moments later, but to fall in love with a woman already dead? Fate can be a cruel master. Kenji Uchida travelled to America’s San Fransisco State University to study filmmaking before returning to Japan and making this, his debut film, Weekend Blues (ウィーク エンド ブルース) which later went on to claim two awards at the prestigious Pia Film Festival for independent films earning him the scholarship which enabled his next film,

Kenji Uchida travelled to America’s San Fransisco State University to study filmmaking before returning to Japan and making this, his debut film, Weekend Blues (ウィーク エンド ブルース) which later went on to claim two awards at the prestigious Pia Film Festival for independent films earning him the scholarship which enabled his next film,