Is there such a thing as objective truth, or only an agreed upon “reality”? Like many of his early films, Akira Kurosawa’s adaptation of a pair of short stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa is concerned with the idea of authenticity, or the difference between the truth and a lie, but is also acutely aware that the lines between the two aren’t as clear as we’d like them to be largely because we lie to ourselves and come to believe our own perceptions as “truth” assuming that it is others who are mistaken or duplicitous.

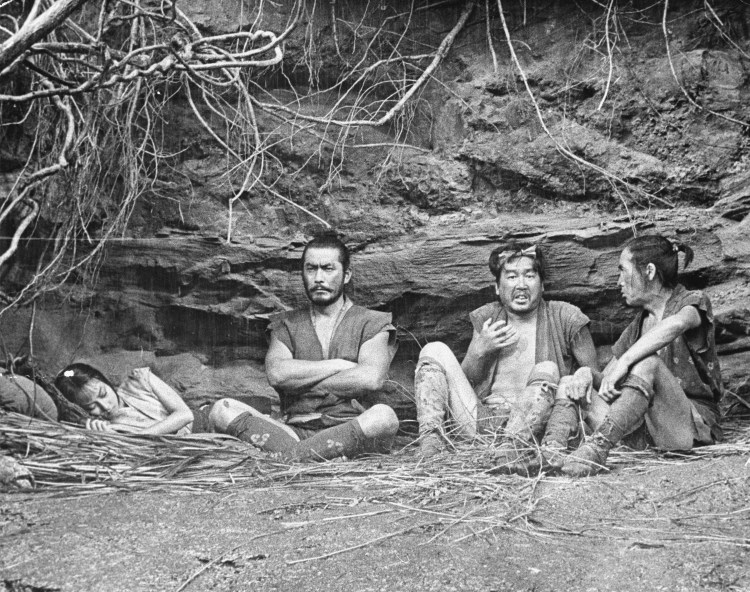

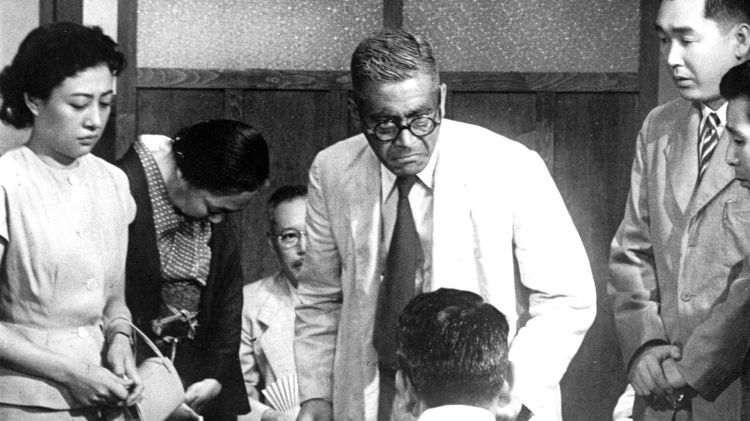

After all, the film opens with the words “I don’t understand”, as the woodsman (Takashi Shimura), who later tells us unprompted that he does not lie, tries to reconcile the conflicting testimonies of a series of witnesses at the trial of the bandit Tajomaru (Toshiro Mifune) who is accused of raping a noble woman (Machiko Kyo) in the forest and killing her husband (Masayuki Mori). At the end of the film it becomes clear that most of his confusion is born of the fact that he witnessed more than he claimed, later presenting a more objective version of the events while justifying his decision not reveal it earlier by saying he didn’t want to get involved. Not wanting to get involved might be understandable, he has six children and presumably won’t be paid for his time nor will he want to risk being accused of something himself. Then again as the cynical peasant (Kichijiro Ueda) sheltering with him at the already ruined Rashomon Gate seems to have figured out, it might equally be that he took the precious dagger repeatedly mentioned in the trial before running off to find the police. He has six children to feed after all.

The woodsman is simply confused if also guilty, but the Buddhist monk (Minoru Chiaki) who saw the couple on the road some days previously has been thrown into existential despair and is on the brink of losing his faith in humanity. He can’t bear to live in a world in which everyone is selfish and dishonest. Yet “dishonest” is not quite the right word to describe the testimony, for there’s reason to believe that the witnesses may believe what they say when saying it or have at least deluded themselves into believing a subjective version of the truth that shows them in a better light than the “objective” might have. At least, none of the suspects are lying in order to escape justice as each confesses to the crime though for varying reasons.

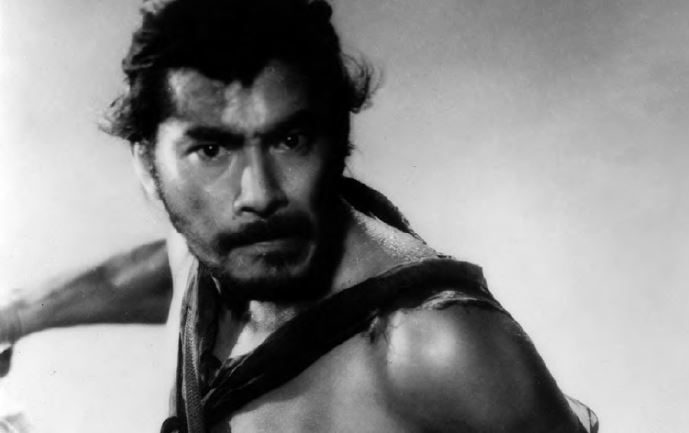

The bandit flatters himself by assuming dominance over the situation, baldly stating that he killed the samurai to rape the wife only she took a liking to him and he killed the husband in a fair fight even remarking on his skill as a swordsman. As we later see Kurosawa frames these fights in a more naturalistic fashion than your average chambara. They are often clumsy and desperate, won more by chance than by skill. Tajomaru also describes the wife as “fierce” in an unwomanly fashion though she is meek and cheerful on the stand and later states that she fainted after her husband rejected her for her “faithlessness” and woke up to find her dagger in his chest, while his beyond the grave testimony delivered via spirit medium claims that he killed himself unable to bear the humiliation of his wife’s betrayal in agreeing to leave with Tajomaru.

As the peasant points out, Tajomaru lies because he is insecure and so tells a story that makes him seem more “heroic” than he actually is, while the wife lies to overcome her shame, and the samurai to reclaim agency over his death and escape the twin humiliations of having been unable to protect his wife and being murdered by a petty bandit. As the three men sheltering under the Rashomon Gate concede, we don’t know our own souls and often resort to narrative to tell ourselves who we are. As usual, the truth is a little of everything, all the tales are partly true and less “lies” than wilful self-delusion to help the witness accept an unpalatable “reality”. Kurosawa perhaps hints at this in his use of extreme closeup while otherwise forcing the viewer into the roles alternately of witness and judge as if we were like the woodman watching from the bushes or hearing testimony from the dais while the action proceeds to the maddening rhythms of a bolero. Despite the hopeless of the situation, the reality that everyone lies and the world is a duplicitous place, the monk’s faith is eventually restored in the acknowledgment that there are truths other than the literal as he witnesses the woodsman’s compassion and humanity, the skies ahead of them beginning to clear as they leave the shelter of the ruined gate for a world which seems no less uncertain but perhaps not so cynical as it had before.

Rashomon is re-released in UK cinemas on 6th January courtesy of BFI.

Re-release trailer (English subtitles)