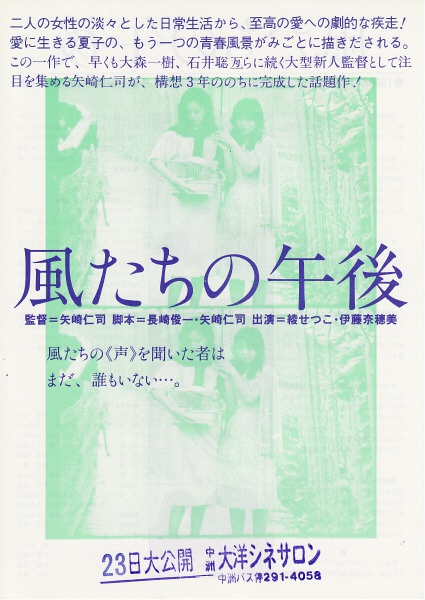

Even in the Japan of 1980, many kinds of love are impossible. Afternoon Breezes (風たちの午後, Kazetachi no gogo), the indie debut from Hitoshi Yazaki follows just one of them as a repressed gay nursery nurse falls hopelessly in love with her straight roommate. Based on a salacious newspaper report of the time, Afternoon Breezes is a textbook examination of obsessive unrequited love as its heroine is drawn ever deeper into a spiral of inescapable despair and incurable loneliness.

Nursery nurse Natsuko (Setsuko Aya) is in love with her hairdresser roommate Mitsu (Naomi Ito), who seems to be completely oblivious of her friend’s feelings. Mitsu has a boyfriend, Hideo (Hiroshi Sugita), and the relationship is becoming serious enough to have Natsuko worried. Hideo, unlike Mitsu, is pretty sure Natsuko is a lesbian and in love with his girlfriend but finds the situation amusing more than anything else. Beginning to go out of her mind with frustration, Natsuko tries just about everything she can to break Mitsu and Hideo up including introducing him to another pretty girl from the nursery, Etsuko (Mari Atake). Hideo is not exactly a great guy and shows interest in Etsuko though does not seem as intent on leaving Mitsu as Natsuko had hoped. Desperate times call for desperate measures and so Natsuko steels herself against her revulsion of men and seduces Hideo on the condition that he end things with her beloved Mitsu. He does, but the plan goes awry when Natsuko realises she is pregnant with Hideo’s child.

Less about lesbianism and more about love which can never be returned slowly eroding a mind, Afternoon Breezes perfectly captures the hopeless fate of its heroine as she idly dreams a future for herself which she knows she will never have. Natsuko buys expensive gifts for her roommate, returns home with flowers and courts her in all of the various ways a shy lover reveals themselves but if Mitsu ever recognises these overtures for what they are she never acknowledges them. Her boyfriend, Hideo, seems more worldly wise and makes a point of cracking jokes about Natsuko, asking Mitsu directly if her friend has a crush on her but Mitsu always laughs the questioning off. Mitsu may know on some level that Natsuko is in love with her, she seems to be aware of her distaste for men even if she tries to take her out to pick one up, but if she does it’s a truth she does not want to own and when it is finally impossible to ignore she will have nothing to do with it.

Despite Mitsu’s ongoing refusal to confront the situation, Natsuko basks in idealised visions of domesticity as she and Mitsu enjoy a romantic walk in the rain only to have their reverie interrupted by a passing pram containing a newborn baby. What Natsuko wants is a conventional family life with Mitsu, including children. After their walk, the pair adopt a pet mouse which Natsuko comes to think of as their “baby” but like a grim harbinger of her unrealisable dream, the mouse dies leading Mitsu to bundle it into a envelope and leave it on a rubbish heap along with Natsuko’s heart and dreams for the future.

When her colleagues at the nursery get stuck into the girl talk and ask Natsuko about boyfriends, her response is that she would not “degrade” herself yet that is exactly what she finally resorts to in an increasingly desperate effort to get close to Mitsu. After her attempts to get him to fall for another girl fail, Natsuko’s last sacrificial offering is her own body, surrendered on the altar of love as she pleads with the heartless Hideo to leave Mitsu for good. Though her bodily submission is painful to watch in her obvious discomfort her mental degradation has been steadily progressing as Hideo deliberately places himself between the two women, even going so far as to disrupt a seaside holiday planned for two by inviting himself along.

Yazaki perfectly captures Natsuko’s ever fracturing mental state through the inescapable presence of the dripping tap in the girls’ apartment which becomes a dangerous ticking in Natsuko’s time bomb mind. Occasionally gelling with clocks and doors and other oppressive noises, the internal banging inside Natsuko’s head only intensifies as she’s forced to endure the literal banging of Mitsu and Hideo’s lovemaking during her romantic getaway. Just as an earlier scene found Natsuko sitting on the swing outside embracing the flowers she’d brought for Mitsu only to find Hideo already there, Natsuko’s fate is to be perpetually left out in the cold, eventually resorting to rifling through her true love’s rubbish and biting into a half eaten apple in a desperate attempt at contact.

Natsuko’s love is an impossible one, not only because Mitsu is unable to return it, but because it is essentially unembraceable. In a society where her love is a taboo, Natsuko is not able to voice her desires clearly or live in an ordinary, straightforward way but is forced to act with clandestine subtlety. After Hideo unwittingly deflowers her and laughs about it, stating that she “must really be gay” Natsuko lunges at him with a knife, suddenly overburdened with one degradation too many. Though the prospect of the baby may raise the possibility of a happy family, albeit an unconventional one, the signs point more towards funerals than christenings, so devoid of hope does Natsuko’s world seem to be. Shot in a crisp 16mm black and white, Afternoon Breezes owes an obvious debt to the art films of twenty years before with its long takes, static camera giving way to handheld, and flower-filled conclusion, but adds an additional layer of youthful anxiety as its heroines find themselves moving into a more prosperous, socially liberal age only to discover some dreams are still off limits.

Post-war cinema took many forms. In Korea there was initial cause for celebration but, shortly after the end of the Japanese colonial era, Korea went back to war, with itself. While neighbouring countries and much of the world were engaged in rebuilding or reforming their societies, Korea found itself under the corrupt and authoritarian rule of Syngman Rhee who oversaw the traumatic conflict which is technically still ongoing if on an eternal hiatus. Yu Hyun-mok’s masterwork Aimless Bullet (오발탄, Obaltan) takes place eight years after the truce was signed, shortly after mass student demonstrations led to Rhee’s unseating which was followed by a short period of parliamentary democracy under Yun Posun ending with the military coup led by Park Chung-hee and a quarter century of military dictatorship. Of course, Yu could not know what would come but his vision is anything but hopeful. Aimless Bullets all, this is an entire nation left reeling with no signposts to guide the way and no possible destination to hope for. All there is here is tragedy, misery, and inevitable suffering with no possibility of respite.

Post-war cinema took many forms. In Korea there was initial cause for celebration but, shortly after the end of the Japanese colonial era, Korea went back to war, with itself. While neighbouring countries and much of the world were engaged in rebuilding or reforming their societies, Korea found itself under the corrupt and authoritarian rule of Syngman Rhee who oversaw the traumatic conflict which is technically still ongoing if on an eternal hiatus. Yu Hyun-mok’s masterwork Aimless Bullet (오발탄, Obaltan) takes place eight years after the truce was signed, shortly after mass student demonstrations led to Rhee’s unseating which was followed by a short period of parliamentary democracy under Yun Posun ending with the military coup led by Park Chung-hee and a quarter century of military dictatorship. Of course, Yu could not know what would come but his vision is anything but hopeful. Aimless Bullets all, this is an entire nation left reeling with no signposts to guide the way and no possible destination to hope for. All there is here is tragedy, misery, and inevitable suffering with no possibility of respite. Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Masaki Kobayashi had a relatively short career of only 22 films. Politically uncompromising and displaying an unflinching eye towards Japan’s recent history, his work was not always welcomed by studio bosses (or, at times, audiences). Beginning his post-war career as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi’s first few films are perhaps closer to the veteran director’s trademark melodrama but in 1953 Kobayashi struck out with a more personal project in the form of

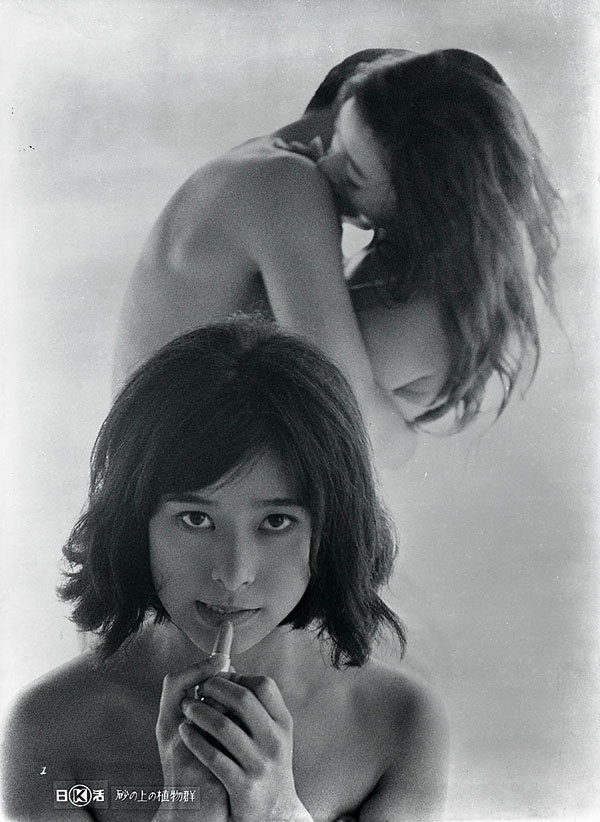

Masaki Kobayashi had a relatively short career of only 22 films. Politically uncompromising and displaying an unflinching eye towards Japan’s recent history, his work was not always welcomed by studio bosses (or, at times, audiences). Beginning his post-war career as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi’s first few films are perhaps closer to the veteran director’s trademark melodrama but in 1953 Kobayashi struck out with a more personal project in the form of  Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.

Lee Man-hee was one of the most prolific and high profile filmmakers of Korea’s golden age until his untimely death at the age of 43 in 1975. Like many directors of the era he had his fare share of struggles with the censorship regime enduring more than most when he was arrested for contravention of the code with his 1965 film Seven Female POWs and later decided to shelve an entire project in 1968’s

Lee Man-hee was one of the most prolific and high profile filmmakers of Korea’s golden age until his untimely death at the age of 43 in 1975. Like many directors of the era he had his fare share of struggles with the censorship regime enduring more than most when he was arrested for contravention of the code with his 1965 film Seven Female POWs and later decided to shelve an entire project in 1968’s  Apichatpong Weerasethakul started as he meant to go on with his debut feature, straddling the borders between art film and surrealist exercise. A cinematic riff on the classic “exquisite corpse” game, Mysterious Object at Noon (ดอกฟ้าในมือมาร, Dokfa Nai Meuman) is equal parts neorealist odyssey and commentary on the human need for constructed narrative (something which the film itself consistently rejects). Shot in a grainy black and white, Apitchatpong’s first effort was filmed over three years travelling the length of the country from North to South inviting everyone from all walks of life to contribute something to the ongoing and increasingly strange brand new oral history.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul started as he meant to go on with his debut feature, straddling the borders between art film and surrealist exercise. A cinematic riff on the classic “exquisite corpse” game, Mysterious Object at Noon (ดอกฟ้าในมือมาร, Dokfa Nai Meuman) is equal parts neorealist odyssey and commentary on the human need for constructed narrative (something which the film itself consistently rejects). Shot in a grainy black and white, Apitchatpong’s first effort was filmed over three years travelling the length of the country from North to South inviting everyone from all walks of life to contribute something to the ongoing and increasingly strange brand new oral history. Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns.

Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns. Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one.

Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one. “Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period.

“Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period.