Things changed after the war, but not as much as some might have hoped. Sadly still topical, Keisuke Kinoshita’s Garden of Women (女の園, Onna no Sono) takes aim both at persistent and oppressive patriarchal social structures and at a compromised educational system which, intentionally or otherwise, systematically stifles attempts at progressive social change. A short few years before student protests would plunge education into crisis, Kinoshita’s film asks why it is that the establishment finds itself in conflict with the prevailing moods of the time and discovers that youth intends to have its brighter future even if it has to fight for it all the way.

Things changed after the war, but not as much as some might have hoped. Sadly still topical, Keisuke Kinoshita’s Garden of Women (女の園, Onna no Sono) takes aim both at persistent and oppressive patriarchal social structures and at a compromised educational system which, intentionally or otherwise, systematically stifles attempts at progressive social change. A short few years before student protests would plunge education into crisis, Kinoshita’s film asks why it is that the establishment finds itself in conflict with the prevailing moods of the time and discovers that youth intends to have its brighter future even if it has to fight for it all the way.

The setting is an exclusive private woman’s university in the elegant historical city of Kyoto. The ladies who attend this establishment are mostly from very wealthy families who have decided to educate their daughters at the college precisely because of its image of properness. As one student will later put it, there are two kinds of girls at the school – those who genuinely want to study in order to make an independent life for themselves and intend to look for work after graduation, and those who are merely adding to their accomplishments in order to hook a better class of husband. Everyone, however, is subject to a stringent set of rules which revolves around the formation of the ideal Japanese woman through strictly enforced “moral education” which runs to opening the girls’ private letters and informing their families of any “untoward” content, and requiring that permission be sought should the girls wish to attend “dances” or anything of that nature.

As might be expected, not all of the girls are fully compliant even if they superficially conform to the school’s rigid social code. Scolded for her “gaudy” hair ribbon on the first day of school, Tomiko (Keiko Kishi) rolls her eyes at the over the top regulations and enlists the aid of the other girls to cover for her when she stays out late with friends but her resistance is only passive and she has no real ideological objection towards the ethos of the school other than annoyance in being inconvenienced. Tomiko is therefore mildly irritated by the presence of the melancholy Yoshie (Hideko Takamine). Three years older, she’s come to college late and is struggling to keep up with classes but is, ironically enough, prevented from studying by the same school rules which insist she go to bed early.

Meanwhile, dorm mate Akiko (Yoshiko Kuga), from an extraordinarily wealthy and well connected family, is becoming increasingly opposed to the oppressive atmosphere at the school. However, as another already politically active student points out, Akiko’s background means there are absolutely no stakes for her in this fight. She has never suffered, and likely never will, because she always has been and always will be protected by her privilege. Fumie (Kazuko Yamamoto), a hardline socialist, doubts Akiko’s commitment to the cause, worrying that in the end she is only staging a minor protest against her family and will eventually drift away back to her world of ski lodges and summer houses. Despite her ardour, Akiko finds it hard to entirely dispute Fumie’s reasoning and is at constant battle with herself over her true feelings about the state of the modern world as it relates to herself individually and for women in general.

This is certainly a fiercely patriarchal society. Even though these women are in higher education, they are mostly there to perfect the feminine arts which are, in the main, domestic. They are not being prepared for the world of work or to become influential people in their own right, but merely to support husbands and sons as pillars of the rapidly declining social order that those who sent them there are desperate to preserve. For many of the girls, however, times are changing though more for some than others. Tomiko rolls her eyes and does as she pleases, within reason, and even if she eventually wants to see things change at the school it is mostly for her own benefit. She sees no sense in Akiko’s desire for reform as a stepping stone to wider social change, and perhaps even fears the kinds of changes that Akiko and Fumie are seeking.

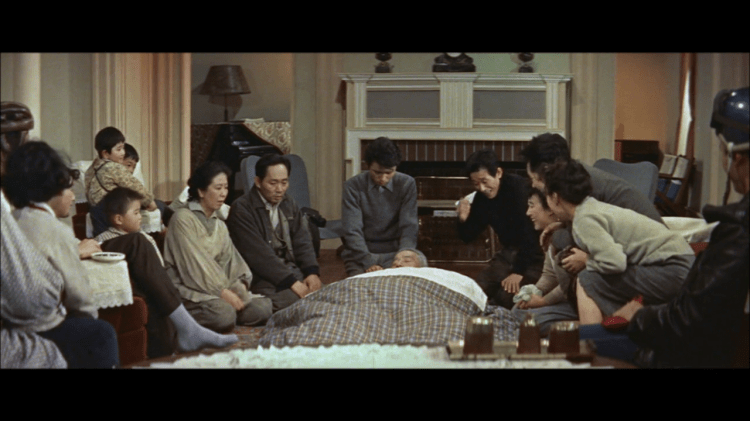

Akiko and Fumie, and to an extent, Tomiko, seem to have a degree of agency that others do not as seen in the tragic story of Yoshie whose life has been largely ruined thanks to the selfish and heartless actions of her father. From a comparatively less wealthy family, Yoshie worked in a bank for three years during which time she met and fell in love with an earnest young man named Shimoda (Takahiro Tamura). However, her father, having become moderately successful, developed an appetite for social climbing and is determined she marry “well” to increase his own sense of superiority as a fully fledged member of the middle classes. He sees his daughter as nothing more than a tool or extension of himself and cares nothing for her thoughts or feelings. In order to resist his demands for an arranged marriage, Yoshie enrolled in school and is desperate to stay long enough for Shimoda to finish his education so they can marry.

Yoshie is trapped at every turn – she cannot rely on her family, she cannot simply leave them, she cannot yet marry, if she leaves the school she will be reliant on a man who effectively intends to sell her, but her life here is miserable and there is no one who can help her. All she receives from the educational establishment is censure and the instruction to buck up or get kicked out. She feels herself a burden to the other girls who regard her as dim and out of place thanks to their relatively minor age gap and cannot fully comprehend her sense of anxiety and frustration.

Finally standing up to the uncomfortably fascistic school board the girls band together to demand freedoms both academic and social, insisting that there can be no education without liberty, but the old ways die hard as they discover most care only for appearances, neatly shifting the blame onto others in order to support their cause. “Why must we suffer so?” Yoshie decries at a particularly low point as she laments her impossible circumstances. Why indeed. The oppressive stricture of the old regime may eventually cause its demise but it intends to fight back by doubling down and the fight for freedom will be a long one even if youth intends to stand firm.

Titles and opening scene (no subtitles)

Junichiro Tanizaki is giant of Japanese literature whose work has often been adapted for the screen with

Junichiro Tanizaki is giant of Japanese literature whose work has often been adapted for the screen with