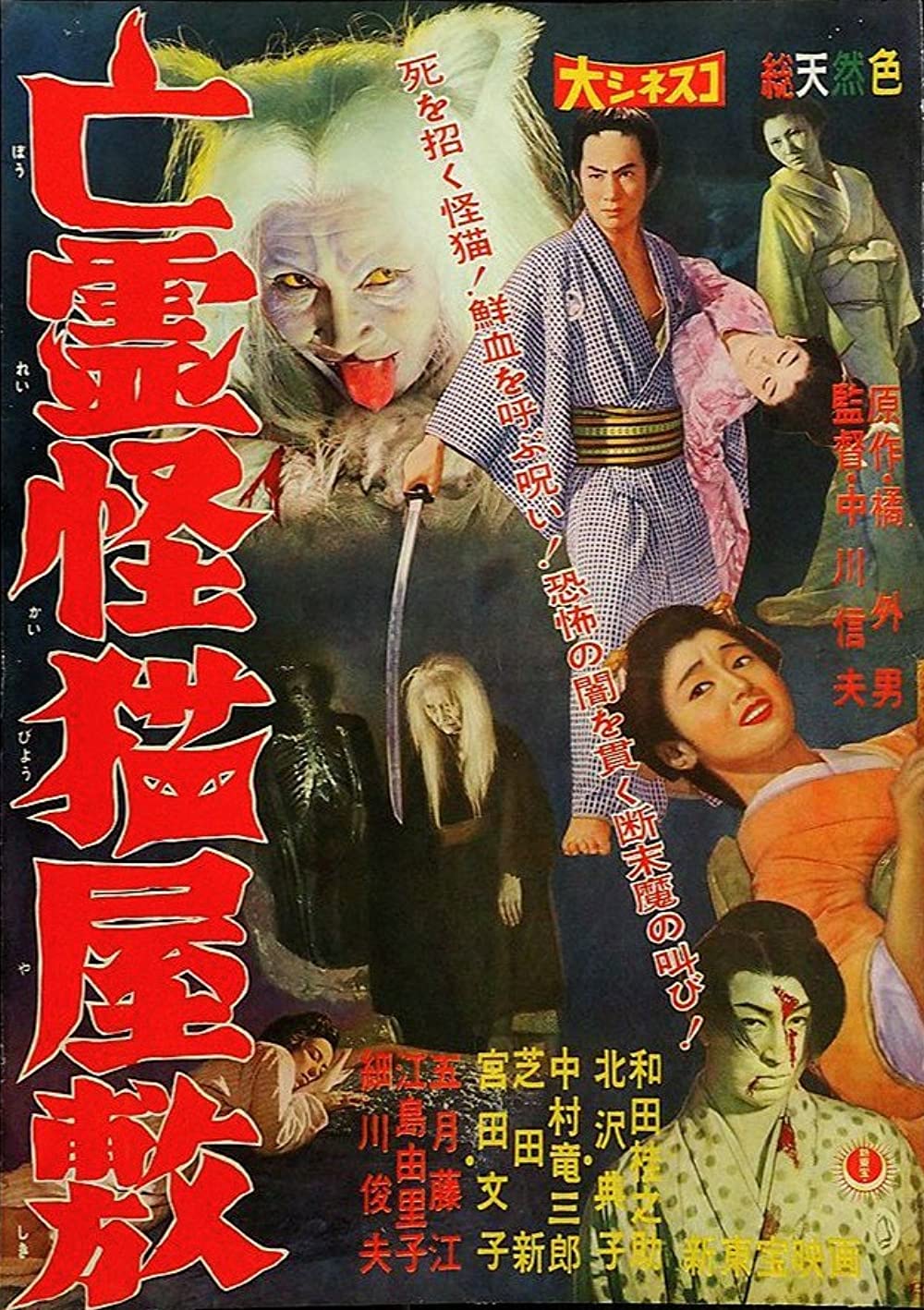

A treacherous military police officer comes to embody the evils of war in Nobuo Nakagawa’s eerie psychological horror, Ghost in the Regiment (憲兵と幽霊, Kenpei to Yurei). Kyotaro Namiki’s The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty (憲兵とバラバラ死美人, Kenpei to Barabara Shibijin) had been a big hit the previous year so studio head Mitsugi Okura tasked Nakagawa with producing something similar at which point he proposed a film centring on “treachery and patriotism”. The Japanese title closely resembles that of Namiki’s film in beginning “the military policeman and…” as if it were a continuation of an ongoing series but is otherwise unrelated and could even be interpreted to suggest that the protagonist is both malevolent supernatural entity and military policeman.

Lieutenant Namishima (Shigeru Amachi) is indeed later described as “the embodiment of evil” and his desire for conquest, in this case of a woman about to marry another man whom he will eventually win and discard, is reflective of the destructive lust for imperialist expansion. When Akiko (Naoko Kubo) marries another member of the military police, Tazawa (Shoji Nakayama), in the autumn of 1941, Sergeant Takashi (Fujio Murakami) jokes with Namishima that he has “failed to win the girl”, but Namishima merely smirks and explains that he’s playing a long game, “The true spirit of a warrior is found in the final victory.” Soon after he frames Tazawa for having stolen secret documents he himself has sold to Chinese spy Zhang (Arata Shibata), subjecting him to heinous torture and having both Akiko and his mother (Fumiko Miyata) tortured in front of him to force Tazawa to confess. Thereafter he has him executed by firing squad but Tazawa, strung up on a cross, continues to protest his innocence until the final moment issuing a curse on all those that have wronged him.

Unlike some of Nakagawa’s other films, the ghosts here are less supernatural than they are psychological. Namishima has frequent flashbacks and visions that remind him of his crimes and is quite literally haunted by his guilt while refusing to admit that he feels any. It seems that he harbours strong resentment towards the military and implicitly towards the militarist regime and emperor having been rejected by the military academy because his father had committed suicide. His treachery is revenge but also equal parts self-destruction and a wilful bid to assert himself through his transgressions marvelling at his success in becoming the sort of person who could betray his own country and kill his own people. Both Tazawa and his brother (also played by Shoji Nakayama), who later joins the military police hoping to investigate the circumstances of his death, were graduates of the military academy and therefore idealised cogs in the military machine.

Somewhat uncomfortably, the righteousness of Tazawa’s brother effectively legitimises the militarists in suggesting that a man like Namishima is an aberrance unreflective of the militarist ideal. “Ignoring the innocent goes against all the military police stand for”, Tazawa earnestly tells Namishima when he attempts to cut corners framing another suspect for his own ends, lending the military police an air of legitimacy they may not have had in reality when we might ask ourselves what exactly it was that they “stood for” which is more likely the nihilistic amorality to which the narcissistic Namishima subscribes. As he said, women lose their lustre once he’s got them. Having pretended to be a friend to Akiko in her widowhood, he rapes her during an air raid and it’s at this point that Japan begins rapidly losing the war as Namishima’s moral decline mirrors the fortunes of his nation. Having got what he wanted, he callously discards her and is transferred to Manchuria where he continues to work with Zhang and his wife, Ruri/Honglei (Yoko Mihara), with whom he has something like a more genuine romance.

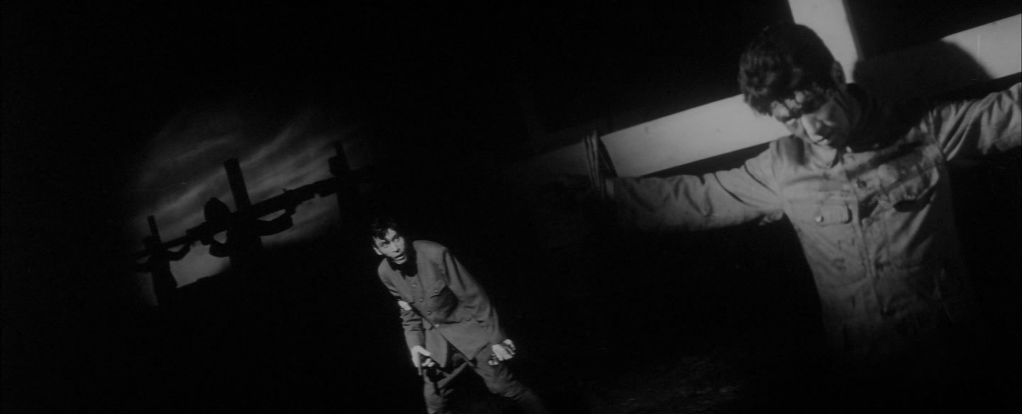

His crimes will, however, catch up with him and it’s in Manchuria that his schemes begin to unravel not least because of the unsettlement that the presence of Tazawa’s brother, who has been seconded to his unit, causes him. The film’s surreal conclusion takes place in a Christian graveyard with Namishima surrounded by crosses which align with the crucifix on which Tazawa was executed. The crucifix itself would have no particular religious connotation in Japan and is simply a convenient way of constraining someone for execution but here takes on a symbolic dimension in confronting Namishima with his sins of transgression. Soon he is surrounded by hundreds of Tazawas on crosses, echoing the many men who were in effect murdered by the imperialist regime in a war fuelled by the same lust for conquest that motivated Namishima. Nakagawa’s camera takes on the role of an observer, sometimes comically swooping between talking heads as if following an ongoing conversation while later rocking in unsteadiness as Namishima begins to lose his grip on reality, finally confronted with the “ghosts” that surround him.

Original trailer (no subtitles)