Japanese Girls Never Die (アズミ・ハルコは行方不明, Azumi Haruko wa Yukuefumei) but, like old soldiers, only fade away in Daigo Matsui’s impassioned adaptation of the Mariko Yamauchi novel. Crushed by a misogynistic society, these are women who may well want to disappear if only as an alternative to finally being forced into submission to the predefined paths of womanhood – i.e. marriage and motherhood (and nothing else) that have been carved out for them. The young are, however, fighting back if in less than admirable ways. The best revenge on an oppressive society may be living well in one’s own way, but when that same society is at great pains to frustrate your goal the options are few.

Japanese Girls Never Die (アズミ・ハルコは行方不明, Azumi Haruko wa Yukuefumei) but, like old soldiers, only fade away in Daigo Matsui’s impassioned adaptation of the Mariko Yamauchi novel. Crushed by a misogynistic society, these are women who may well want to disappear if only as an alternative to finally being forced into submission to the predefined paths of womanhood – i.e. marriage and motherhood (and nothing else) that have been carved out for them. The young are, however, fighting back if in less than admirable ways. The best revenge on an oppressive society may be living well in one’s own way, but when that same society is at great pains to frustrate your goal the options are few.

As per the title, 28-year-old admin assistant Haruko Azuma (Yu Aoi) has gone missing. Her face, stolen from her missing poster, has been co-opted by a pair of petty punk idiots trying to come-up with a viral graffiti tag to rival Obey, but there’s no art or intention behind their minor act of social transgression so much as bravado and pithy rebellion. Nevertheless, Haruko’s image, plastered throughout the city, has become a hot topic on Japan’s social networking sites where a hundred trolls wade in with their prognostications and salacious fantasies of her violent death at the hands of a sex maniac.

Meanwhile, in an ironic subversion of the normalities of city life, young men have been urged to avoid walking alone at night following a spate of attacks by a gang of rabid school girls taking revenge on the male sex. No exact motive is given for their crusade save the missing poster that precedes Haruko’s and asks for information on a disappeared school girl, but goodness knows they have enough obvious reasons to have decided on a course of vigilante justice.

Haruko’s world is one defined by entrenched sexism. At 28 she finds herself embarrassed to be a still single woman at a wedding while a chance encounter with a school friend (Huwie Ishizaki) at a supermarket leads to more awkwardness when he pointedly remarks he assumed she’d be a housewife by now, and that she looks “old”. At work, Haruko’s colleague Yoshizawa (Maho Yamada), 37 and still unwed, is the butt of hundred jokes for the two middle-aged men who, for some reason, are their bosses though they hardly seem to do any work and automatically earn seven times Yoshizawa’s salary. The bosses urge Haruko to dress in more feminine fashions, asking invasive questions about her personal life while disparaging single women like Yoshizawa who they blame for Japan’s declining birthrate and a related raise in their taxes, avowing that women over 35 are essentially pointless seeing as their eggs are already “rotten”. Yoshizawa has developed a thick skin for their constant needling, realising that it amounts to an odd combination of sexual harassment and constructive dismissal campaign. Unwilling to pay a “higher” salary to an “older” woman, they are waiting for her to quit so they can hire a young and pretty new girl who will be naive enough to accept the pittance they intend to pay her.

It might be thought that the attitudes of Haruko’s bosses are a reflection of their generation, but the two young punks, Yukio (Taiga) and Manabu (Shono Hayama), are no different. 20-year-old Aina (Mitsuki Takahata), a bar girl with ambitions to enter the beauty business, gets swept into their unpleasant orbit after getting into a “relationship” with Yukio, but Yukio thinks of her only as a plaything, even going so far as to encourage the shy Manabu to try his luck because (he claims contemptuously) Aina is the kind of girl who’ll go with anyone. Later she becomes a key part of their mini graffiti movement, but once the pair start to get a little recognition they essentially erase Aina from the story taking all the credit for themselves. Aina, poignantly looking up at the poster advertising the boys’ big moment in the same way she had gazed at Haruko’s missing poster on the police station notice board, realises she’s finally had enough of all their lies and of being made to feel invisible in a society which refuses to recognise her as anything more than an object for exploitation.

Haruko’s face is literally plastered all over town, but she remains essentially faceless, her image stolen and stripped of its identity to be repackaged as a soulless symbol for two idiotic boys who not only do not care who she is or might have been but only seek to profit from claiming to be allies in a struggle while simultaneously propping up the opposing side. The image does, however, gain its own independent power, speaking for all the oppressed and belittled women who find themselves essentially disappeared in being forced to abandon their hopes and dreams in the face of extreme social pressure. The school girls are fighting back – the next generation will (perhaps) not be so keen to remain complicit in the social codes which restrict their prospects. Then again, as the image of Haruko tells one of her lost disciples, the best revenge is living well. Choosing to absent oneself from a system of social control, going missing in a more positive sense, may be the best option of all.

Screened as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2018.

Screening again:

- Dundee Contemporary Arts – 26 February 2018

- HOME – 27 February 2018

- Phoenix Leicester – 1 March 2018

- Filmhouse – 3 March 2018

- Showroom Cinema – 6 March 2018

- Firstsite – 9 March 2018

- Exeter Phoenix – 13 March 2018

- Queen’s Film Theatre – 18 March 2018

Original trailer (English subtitles)

The

The  Yo Oizumi stars as a high school teacher investigating the disappearance of a friend in another darkly comic, twist filled farce from Kenji Uchida (

Yo Oizumi stars as a high school teacher investigating the disappearance of a friend in another darkly comic, twist filled farce from Kenji Uchida ( Kazuya Shiraishi (

Kazuya Shiraishi ( When a schoolgirl falls off a roof foul play is suspected. Who better to investigate than her fellow members of the literature club at an elite academy catering to the daughters of the rich and famous?

When a schoolgirl falls off a roof foul play is suspected. Who better to investigate than her fellow members of the literature club at an elite academy catering to the daughters of the rich and famous? A young reporter (Satoshi Tsumabuki) investigates the brutal murder of a model family whilst trying to support his younger sister (Hikari Mitsushima) who is currently in prison for child neglect while his nephew remains in critical condition in hospital. Interviewing friends and acquaintances of the deceased, disturbing truths emerge concerning the systemic evils of social inequality.

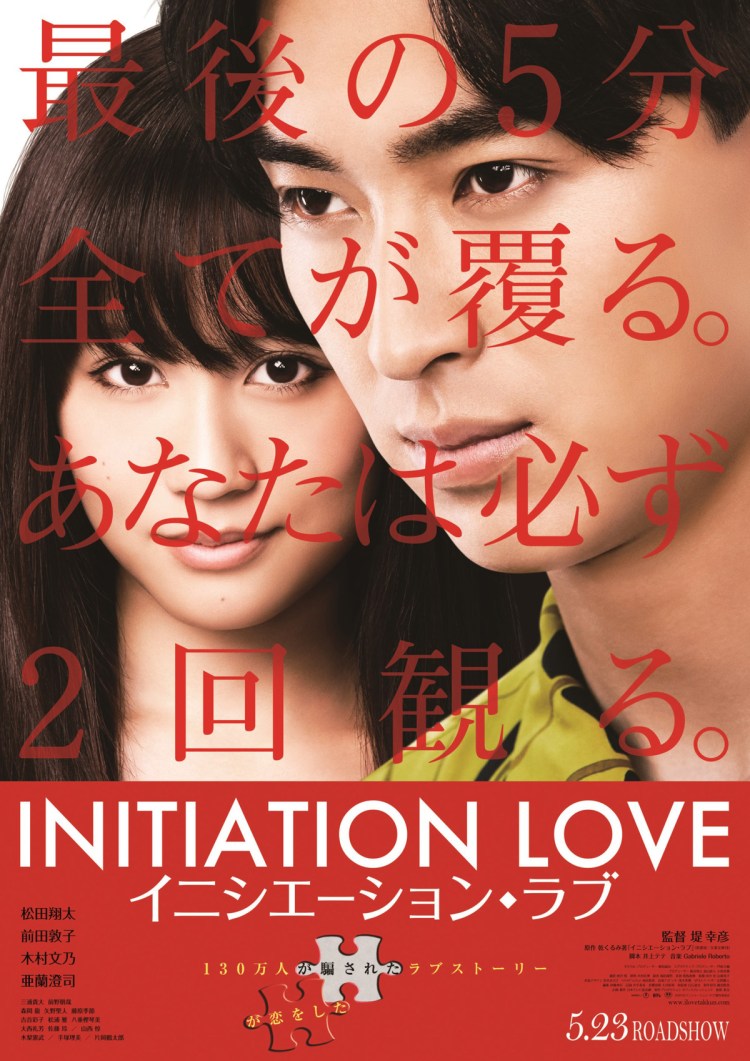

A young reporter (Satoshi Tsumabuki) investigates the brutal murder of a model family whilst trying to support his younger sister (Hikari Mitsushima) who is currently in prison for child neglect while his nephew remains in critical condition in hospital. Interviewing friends and acquaintances of the deceased, disturbing truths emerge concerning the systemic evils of social inequality.  Based on a best selling romantic novel which captured the hearts of readers across Japan, Initiation Love sets out to expose the dark and disturbing underbelly of real life romance by completely reversing everything you’ve just seen in a gigantic twist five minutes before the film ends…

Based on a best selling romantic novel which captured the hearts of readers across Japan, Initiation Love sets out to expose the dark and disturbing underbelly of real life romance by completely reversing everything you’ve just seen in a gigantic twist five minutes before the film ends… A young woman goes missing and unwittingly becomes the face of a social movement in Daigo Matsui’s anarchic examination of a misogynistic society.

A young woman goes missing and unwittingly becomes the face of a social movement in Daigo Matsui’s anarchic examination of a misogynistic society. A brother and sister are orphaned after a natural disaster and taken in by relatives but struggle to come to terms with the aftermath of such great loss.

A brother and sister are orphaned after a natural disaster and taken in by relatives but struggle to come to terms with the aftermath of such great loss. Miwa Nishikawa adapts her own novel in which a self-centred novelist is forced to face his own delusions when his wife is killed in a freak bus accident.

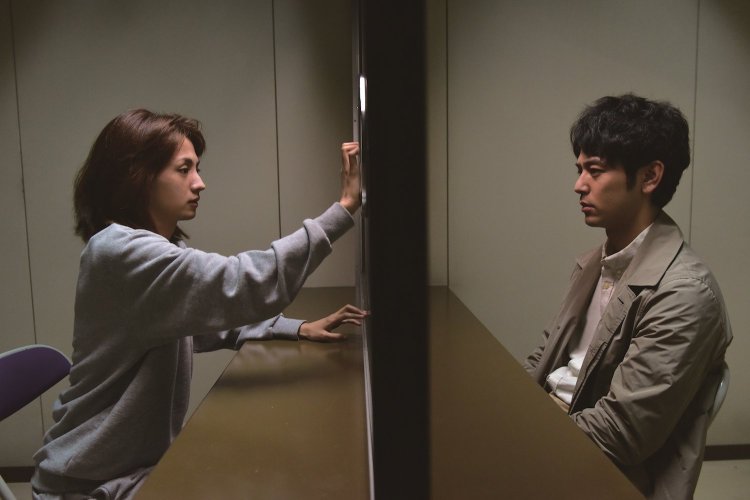

Miwa Nishikawa adapts her own novel in which a self-centred novelist is forced to face his own delusions when his wife is killed in a freak bus accident.  When the statute of limitations passes on a series of unsolved murders, a mysterious man (Tatsuya Fujiwara) suddenly comes forward and confesses while the detective (Hideaki Ito) who is still haunted by his inability to catch the killer has his doubts in Yu Irie’s adaptation of Jung Byoung-Gil’s Korean crime thriller Confession of Murder.

When the statute of limitations passes on a series of unsolved murders, a mysterious man (Tatsuya Fujiwara) suddenly comes forward and confesses while the detective (Hideaki Ito) who is still haunted by his inability to catch the killer has his doubts in Yu Irie’s adaptation of Jung Byoung-Gil’s Korean crime thriller Confession of Murder. Toma Ikuta stars as maverick cop Reiji in Takashi Miike’s madcap manga adaptation. Reiji has been kicked off the force for trying to arrest a councillor who was molesting a teenage girl but gets secretly rehired to go undercover in Japan’s best known yakuza conglomerate.

Toma Ikuta stars as maverick cop Reiji in Takashi Miike’s madcap manga adaptation. Reiji has been kicked off the force for trying to arrest a councillor who was molesting a teenage girl but gets secretly rehired to go undercover in Japan’s best known yakuza conglomerate. Yoshihiro Nakamura (

Yoshihiro Nakamura ( Yuzo Kawashima would have turned 100 in 2018. A comic tale of life on the Osakan margins, Room For Let is a perfect example of the director’s well known talent for satire and stars popular comedian Frankie Sakai as an eccentric writer/translator-cum-konnyaku-maker whose life is turned upside down when a pretty young potter moves into the building.

Yuzo Kawashima would have turned 100 in 2018. A comic tale of life on the Osakan margins, Room For Let is a perfect example of the director’s well known talent for satire and stars popular comedian Frankie Sakai as an eccentric writer/translator-cum-konnyaku-maker whose life is turned upside down when a pretty young potter moves into the building. Embittered 55 year old OL Setsuko gets a new lease on life when introduced to an unusual English conversation teacher, John, who gives her a blonde wig and rechristens her Lucy. “Lucy” falls head over heels for the American stranger and decides to follow him all the way to the states…

Embittered 55 year old OL Setsuko gets a new lease on life when introduced to an unusual English conversation teacher, John, who gives her a blonde wig and rechristens her Lucy. “Lucy” falls head over heels for the American stranger and decides to follow him all the way to the states…  A remake of Korean hit

A remake of Korean hit  A small boy recruits the mysterious samurai “No Name” as a bodyguard after his dog is injured in an ambush in the landmark animation from 2007.

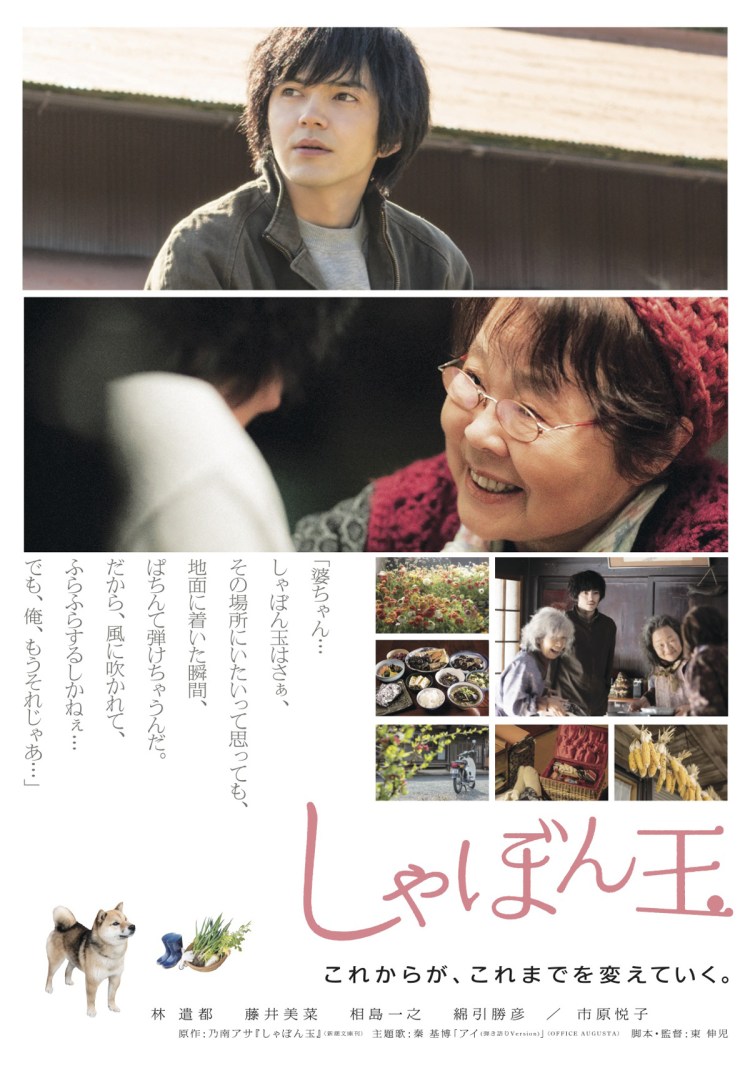

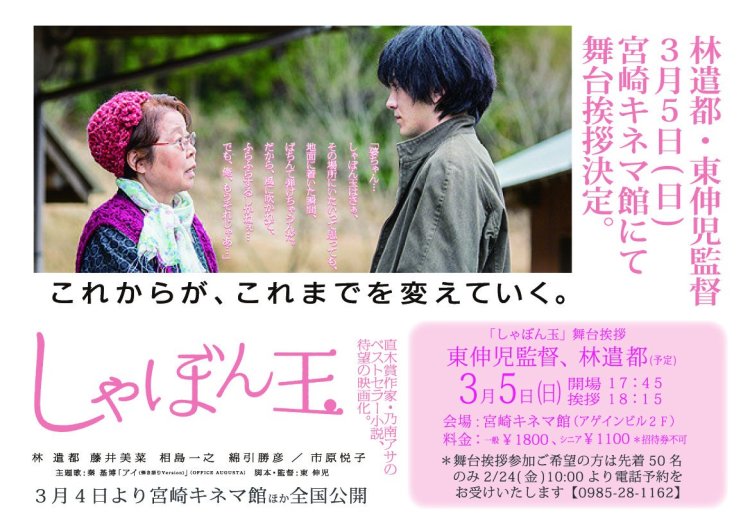

A small boy recruits the mysterious samurai “No Name” as a bodyguard after his dog is injured in an ambush in the landmark animation from 2007. A no good lowlife makes his way by stealing from elderly women but experiences a change of heart when he’s taken in by a kindly old lady deep in the mountains.

A no good lowlife makes his way by stealing from elderly women but experiences a change of heart when he’s taken in by a kindly old lady deep in the mountains.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness. As Japan’s society ages, the lives of older people have begun to take on an added dimension. Rather than being relegated to the roles of kindly grandmas or grumpy grandpas, cinema has finally woken up to the fact that older people are still people with their own stories to tell even if they haven’t traditionally fitted established cinematic genres. Of course, some of this is down to the power of the grey pound rather than an altruistic desire for inclusive storytelling but if the runaway box office success of A Sparkle of Life (燦燦 さんさん, Sansan) is anything to go by, there may be more of these kinds of stories in the pipeline.

As Japan’s society ages, the lives of older people have begun to take on an added dimension. Rather than being relegated to the roles of kindly grandmas or grumpy grandpas, cinema has finally woken up to the fact that older people are still people with their own stories to tell even if they haven’t traditionally fitted established cinematic genres. Of course, some of this is down to the power of the grey pound rather than an altruistic desire for inclusive storytelling but if the runaway box office success of A Sparkle of Life (燦燦 さんさん, Sansan) is anything to go by, there may be more of these kinds of stories in the pipeline.