At the very beginning of Kim Jong-jin’s Underground Rendezvous (만남의 광장, Mannamui Gwangjang), a group of kindly villagers in the north of Korea are caught by surprise when they unwittingly help to build the 38th parallel – a series of fortifications which will divide them from one another forevermore. Family members are trapped on different sides of an artificial border by a matter of accident rather than choice, a decision effectively made for them by the Americans and Russians amping up cold war hostility in engineering a proxy war over war-torn Korea.

At the very beginning of Kim Jong-jin’s Underground Rendezvous (만남의 광장, Mannamui Gwangjang), a group of kindly villagers in the north of Korea are caught by surprise when they unwittingly help to build the 38th parallel – a series of fortifications which will divide them from one another forevermore. Family members are trapped on different sides of an artificial border by a matter of accident rather than choice, a decision effectively made for them by the Americans and Russians amping up cold war hostility in engineering a proxy war over war-torn Korea.

30 years after the villagers sealed their own fates through being overly helpful, the South Korea of the 1980s is perhaps not so different from its Northern counterpart. A brief hope for democracy had once again been dashed and the land remained under the yoke of a cruel and oppressive dictatorship. Young-tan (Im Chang-jung), a boy from a poor village, is determined to escape his life of poverty by travelling to Seoul and studying to become a teacher. However, within five minutes of exiting the station, his country bumpkin ways see his only suitcase swiped by a street thief. An attempt to report the crime only gets him into trouble and so Young-tan is sent to a “re-education” camp in the mountains. Falling off the back of a truck, he gets lost and eventually ends up in a remote village where they assume, ironically enough, that he is the new teacher they’ve been expecting for the local school. The village, however, has a secret – one that’s set to be exposed thanks to Young-tan’s questions about a beautiful lady he saw bathing at the local watering hole.

Young-tan turns out to be a pretty good teacher, though not exactly the sharpest knife in the drawer. The village’s big secret is that the divided families were so attached to each other that they each started digging tunnels to the other side shortly after the wall went up and eventually met somewhere in the middle where they’ve built a large cave they use for underground reunions. Apparently existing for 30 years, no one outside of trusted citizens on either side knows about the tunnel’s existence. No one has used it to switch sides, the only purpose of the tunnel is for relatives and friends to mingle freely in defiance of the false division that’s been inflicted on them by outside forces.

Young-tan, however, is fixated on the bathing woman who turns out to be North Korean Sun-mi (Park Jin-hee) – the sister-in-law of the village chief. Thinking only of his crush and also a comparative innocent and devotee of the moral conservatism of ‘80s Korea, Young-tan catches sight of Sun-mi and the village chief and is convinced that the old man is molesting an innocent young maiden. He sets out to convince the villagers of this, little knowing the truth and unwittingly threatening to expose the entire enterprise through failing to understand the implications of his situation.

Kim pulls his punches on both sides of the parallel, only hinting at the oppressions present on each side of the border with Sun-mi fairly free in the North, working as the army propaganda officer in charge of the noisy broadcasts which attempt to tempt South Koreans to embrace the egalitarian “freedoms” on offer to defectors. Meanwhile the villagers in the South live fairly isolated from the unrest felt in the rest of the country, continuing a traditional, rural way of life but are also under the supervision of a local troop of bored army conscripts on the look out for North Korean spies. Nobody wants to defect, though perhaps there’d be little point in any case, but everyone longs for the day when families can all live together happily as they used to free from political interference.

Satire, however, is not quite the main aim. An absurd subplot sees the “real” teacher marooned on his own after taking a detour and accidentally standing on a landmine leaving him rooted to the spot on pain of death, but the majority of the jokes rest on Young-tan’s “misunderstandings” as a village outsider, goodnatured simpleton, and bullheaded idiot. A final coda tries to inject some meaning by hinting at the effects of repurposing the truth for political gain and the tempered happiness of those who get what they wanted only not quite in the way they wanted it, but it’s too little too late to lend weight to the otherwise uninspired attempts at comedy.

Currently streaming on Netflix UK (and possibly other territories)

Original trailer (no subtitles)

North Koreans have become the go to bad guys recently, and so North Korean spies have become the instigators of fear and paranoia in many a contemporary political thriller. The Suspect (용의자, Yonguija), however, is quick to point the finger at a larger evil – personal greed, dodgy morals, and the all powerful reach of global corporations. Opting for a high octane action fest rather than a convoluted plot structure, Won’s approach is (mostly) an uncomplicated one as a wronged man pursues his revenge or redemption with no thought for his own future, only to be presented with the unexpected offering of one anyway alongside the equally unexpected bonus of exposing an international conspiracy.

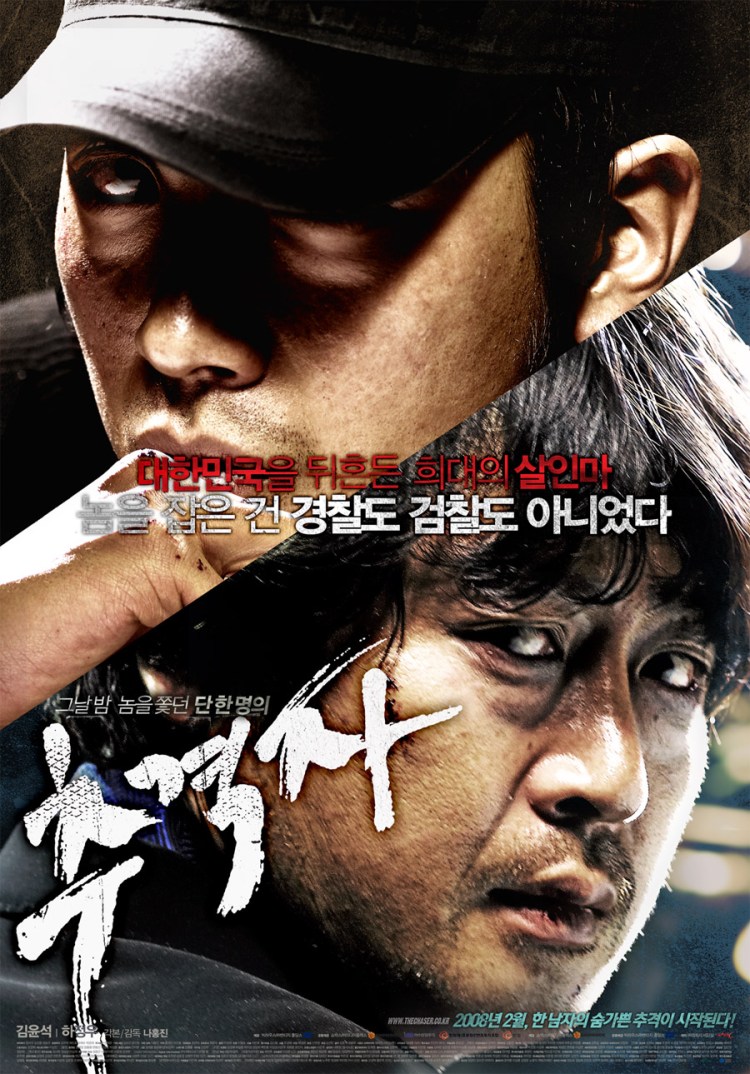

North Koreans have become the go to bad guys recently, and so North Korean spies have become the instigators of fear and paranoia in many a contemporary political thriller. The Suspect (용의자, Yonguija), however, is quick to point the finger at a larger evil – personal greed, dodgy morals, and the all powerful reach of global corporations. Opting for a high octane action fest rather than a convoluted plot structure, Won’s approach is (mostly) an uncomplicated one as a wronged man pursues his revenge or redemption with no thought for his own future, only to be presented with the unexpected offering of one anyway alongside the equally unexpected bonus of exposing an international conspiracy. When it comes to law enforcement in Korea (at least in the movies), your best bet may actually be other criminals or “concerned citizens” as the police are mostly to be found napping or busy trying to cover up for a previous mistake. The Chaser (추격자, Chugyeogja) continues this grand tradition in taking inspiration from the real life serial murder crime spree of Yoo Young-chul , eventually brought to justice in 2005 after pimps came together and got suspicious enough to make contact with a friendly police officer.

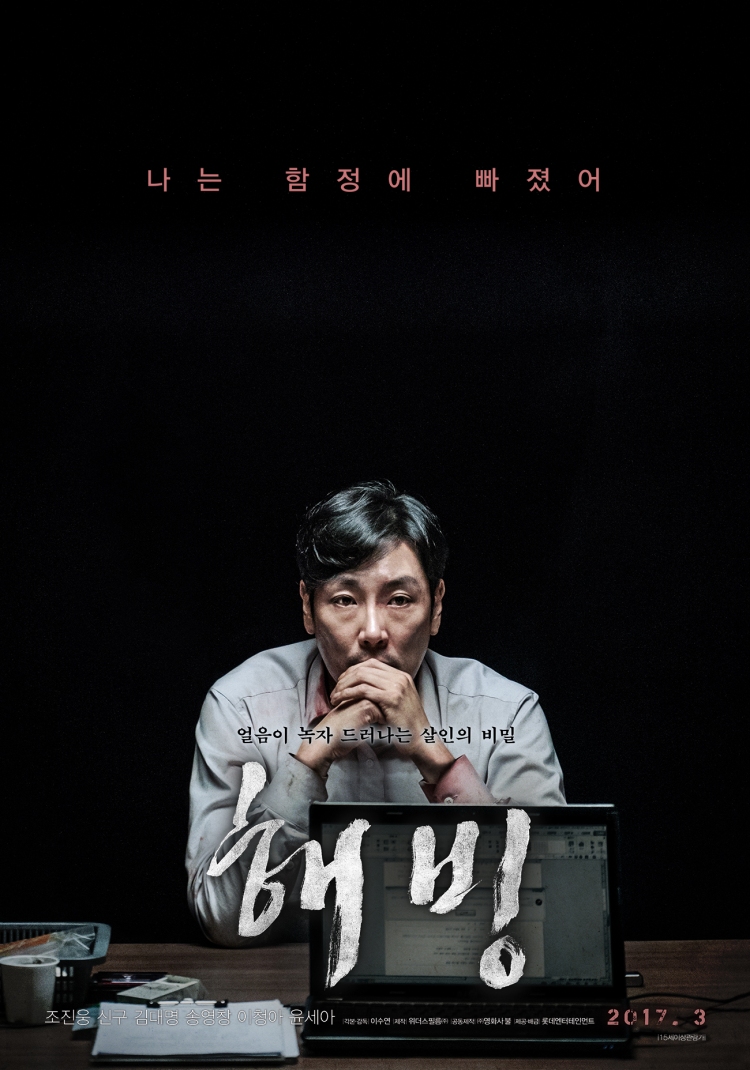

When it comes to law enforcement in Korea (at least in the movies), your best bet may actually be other criminals or “concerned citizens” as the police are mostly to be found napping or busy trying to cover up for a previous mistake. The Chaser (추격자, Chugyeogja) continues this grand tradition in taking inspiration from the real life serial murder crime spree of Yoo Young-chul , eventually brought to justice in 2005 after pimps came together and got suspicious enough to make contact with a friendly police officer. If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects.

If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects.

Many people all over the world find themselves on the zombie express each day, ready for arrival at drone central, but at least their fellow passengers are of the slack jawed and sleep deprived kind, soon be revived at their chosen destination with the magic elixir known as coffee. The unfortunate passengers on an early morning train to Busan have something much more serious to deal with. The live action debut from one of the leading lights of Korean animation Yeon Sang-ho, Train to Busan (부산행, Busanhaeng) pays homage to the best of the zombie genre providing both high octane action from its fast zombie monsters and subtle political commentary as a humanity’s best and worst qualities battle it out for survival in the most extreme of situations.

Many people all over the world find themselves on the zombie express each day, ready for arrival at drone central, but at least their fellow passengers are of the slack jawed and sleep deprived kind, soon be revived at their chosen destination with the magic elixir known as coffee. The unfortunate passengers on an early morning train to Busan have something much more serious to deal with. The live action debut from one of the leading lights of Korean animation Yeon Sang-ho, Train to Busan (부산행, Busanhaeng) pays homage to the best of the zombie genre providing both high octane action from its fast zombie monsters and subtle political commentary as a humanity’s best and worst qualities battle it out for survival in the most extreme of situations. Kim Ki-duk is not known for his conventional approach to morality but even so his 12th feature, The Bow (활, Hwal), takes things to a whole new level of uncomfortable complexity. While nowhere near as extreme as some of Kim’s other work, The Bow takes the form of a fable as an old man and a young girl remain locked inside a mutually dependent relationship which, one way to another, is about to change forever.

Kim Ki-duk is not known for his conventional approach to morality but even so his 12th feature, The Bow (활, Hwal), takes things to a whole new level of uncomfortable complexity. While nowhere near as extreme as some of Kim’s other work, The Bow takes the form of a fable as an old man and a young girl remain locked inside a mutually dependent relationship which, one way to another, is about to change forever.