Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

The heroine, Katsue (Kinuyo Tanaka), has found herself in a difficult position for a woman of 1938. Married off at a young age in payment of a family debt yet rejected by her husband’s family, Katsue’s fortunes fall still further when her husband passes away suddenly leaving her alone and eight months pregnant. Her daughter, Toshi (Kazuko Kojima), is now five years old and Katsue has a good job as a nurse at a local hospital. The job allows her to support herself, her daughter, and her older sister but the problem is that the hospital has a strict policy of not employing married women. Katsue isn’t married anymore, she’s a widow, but the fact that she has a daughter she is raising alone makes her familial status a grey area. She’s been hiding her daughter’s existence from her colleagues in case it costs her the job she needs to survive, but a chance encounter in a park threatens to ruin everything.

Thankfully, Katsue’s colleagues at the hospital turn out to be nice, reasonable people who respond sympathetically on hearing Katsue’s explanation about why she’d avoided telling them the truth about her daughter (and that, crucially, she had been married and the child was conceived legitimately). Her next problem occurs when the son of the hospital’s chief doctor, Kozo (Ken Uehara), returns after graduating university and the pair strike up a friendship which eventually blossoms into romance. Kozo’s father, however, is intent on arranging his marriage to a girl from another medical family – a long held tradition and, in an odd mirror of Katsue’s situation, the marriage is a way of getting additional investment for the rapidly failing clinic. Kozo asks Katsue to run away with him to Kyoto but she still hasn’t told him about Toshi or her previous marriage out of fear of losing not only her new love but her position at the hospital if he rejects her. Just as Katsue is about to go to meet Kozo at the station, Toshi falls ill.

Despite the austerity and conservatism of the times, Aizen Katsura is a very “modern” story in which Katsue’s pragmatic solution to her difficulties is praised and even encouraged. Her life has been an unhappy one in many ways – sold into an arranged marriage at 18, forced out of her hometown after rejection by her husband’s family, and finally widowed in the city, Katsue has been let down at each and every juncture. Alone with a baby, her choices were few and her only support seems to come from her older sister who has no husband of her own (at least, not one that is present), and takes care of Toshi while Katsue has to go out and earn the money to support the family.

Society does not quite know what to do with an anomaly like Katsue who cannot rely on extended family. She needs to support herself and her child but many jobs still have a marriage bar which extends to widows with children. The only options for women who can’t find a solution as elegant as Katsue’s aren’t pleasant, the hospital is a dream come true as it both pays well and is a respectable profession, but if the management found out about Toshi, Katsue could be left out in the cold with little prospect of finding more work despite her nursing qualifications.

The times may be harsh, but the world Katsue inhabits places her on the fringes of the middle classes. Kozo, as young doctor and heir to the clinic (Japanese hospitals are often family businesses) is far above her but is, in some ways, equally constrained. Whilst recognising a duty to his father, Kozo is resolute in refusing the idea of an arranged marriage conducted for financial purposes. He determines to set his own course rather than be railroaded into something which is for his father’s benefit and not his own. Deeply hurt by Katsue’s actions but not attempting to find out why she acted as she did, Kozo enters a depressive spell, sitting around resentfully and not doing much of anything. Luckily for him, the woman his father has picked out, Michiko (Michiko Kuwano), is a thoroughly good person who, once she finds out about Katsue, becomes determined to see that true love wins rather than being shackled to a moody young man and spending the rest of her life in a one sided relationship with someone still pining for a first love.

Katsue’s dreams come true only once she begins to give up on them. Leaving the hospital and returning to her home town with no firm plans, Katsue gets herself a career through luck and talent when a song she enters in a competition is picked up by a leading record label. Music rewards her financially but also gives her a sense of confidence and a purpose which puts her on more of an even footing with Kozo even if he sits in the stalls while her colleagues fill the balcony. Her salvation is both self made and something of a deus ex machina, but the broadly happy ending is intended to give hope to a hopeless age, that miracles can happen and second chances appear once two meet each other openly with full understanding and forgiving hearts.

Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai.

Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai. Kon Ichikawa was born in 1915, just four years later than the subject of his 1989 film Actress (映画女優, Eiga Joyu) which uses the pre-directorial career of one of Japanese cinema’s most respected actresses, Kinuyo Tanaka, to explore the development of Japanese cinema itself. Tanaka was born in poverty in 1909 and worked as a jobbing film actress before being “discovered” by Hiroshi Shimizu and becoming one of Shochiku’s most bankable stars. The script is co-written by Kaneto Shindo who was fairly close to the action as an assistant under Kenji Mizoguchi at Shochiku in the ‘40s before being drafted into the war. A commemorative exercise marking the tenth anniversary of Tanaka’s death from a brain tumour in 1977, Ichikawa’s film never quite escapes from the biopic straightjacket and only gives a superficial picture of its star but seems content to revel in the nostalgia of a, by then, forgotten golden age.

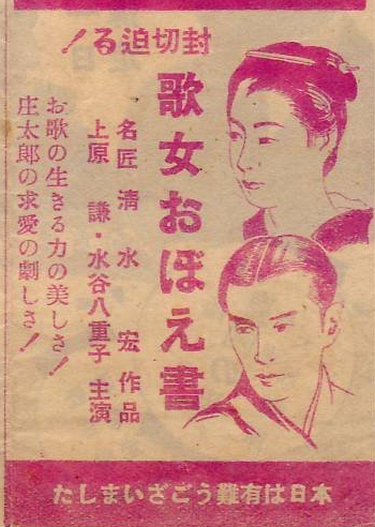

Kon Ichikawa was born in 1915, just four years later than the subject of his 1989 film Actress (映画女優, Eiga Joyu) which uses the pre-directorial career of one of Japanese cinema’s most respected actresses, Kinuyo Tanaka, to explore the development of Japanese cinema itself. Tanaka was born in poverty in 1909 and worked as a jobbing film actress before being “discovered” by Hiroshi Shimizu and becoming one of Shochiku’s most bankable stars. The script is co-written by Kaneto Shindo who was fairly close to the action as an assistant under Kenji Mizoguchi at Shochiku in the ‘40s before being drafted into the war. A commemorative exercise marking the tenth anniversary of Tanaka’s death from a brain tumour in 1977, Ichikawa’s film never quite escapes from the biopic straightjacket and only gives a superficial picture of its star but seems content to revel in the nostalgia of a, by then, forgotten golden age. Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world.

Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence.

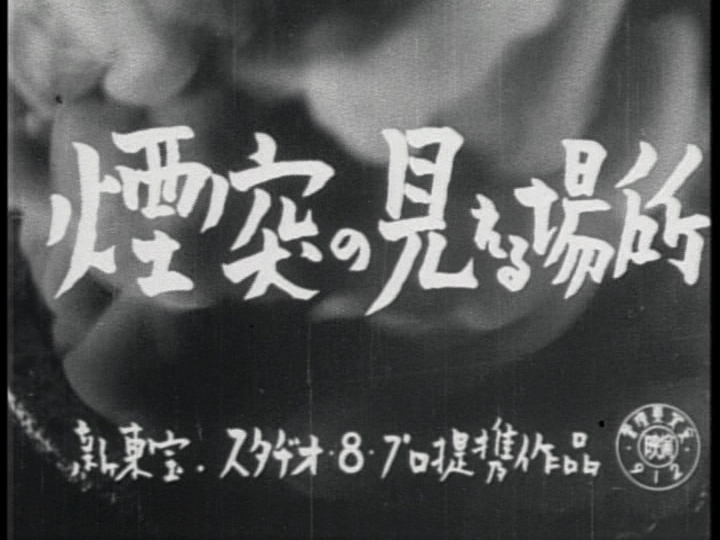

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence. Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.

Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past. Bus trips might be much less painful if only the drivers were all as kind as Mr. Thank You and the passengers as generous of spirit as the put upon rural folk travelling to the big city in Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1936 road trip (有りがとうさん, Arigatou-san). Set in depression era Japan and inspired by a story by Yasunari Kawabata, Mr. Thank You has its share of sorrows but like its cast of down to earth country folk, smiles broadly even through the bleakest of circumstances.

Bus trips might be much less painful if only the drivers were all as kind as Mr. Thank You and the passengers as generous of spirit as the put upon rural folk travelling to the big city in Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1936 road trip (有りがとうさん, Arigatou-san). Set in depression era Japan and inspired by a story by Yasunari Kawabata, Mr. Thank You has its share of sorrows but like its cast of down to earth country folk, smiles broadly even through the bleakest of circumstances. A Japanese tragedy, or the tragedy of Japan? In Kinoshita’s mind, there was no greater tragedy than the war itself though perhaps what came after was little better. Made only eight years after Japan’s defeat, Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1953 film A Japanese Tragedy (日本の悲劇, Nihon no Higeki) is the story of a woman who sacrificed everything it was possible to sacrifice to keep her children safe, well fed and to invest some kind of hope in a better future for them. However, when you’ve had to go to such lengths to merely to stay alive, you may find that afterwards there’s only shame and recrimination from those who ought to be most grateful.

A Japanese tragedy, or the tragedy of Japan? In Kinoshita’s mind, there was no greater tragedy than the war itself though perhaps what came after was little better. Made only eight years after Japan’s defeat, Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1953 film A Japanese Tragedy (日本の悲劇, Nihon no Higeki) is the story of a woman who sacrificed everything it was possible to sacrifice to keep her children safe, well fed and to invest some kind of hope in a better future for them. However, when you’ve had to go to such lengths to merely to stay alive, you may find that afterwards there’s only shame and recrimination from those who ought to be most grateful.