Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era.

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era.

The annual production of The Cherry Orchard has become a firm fixture at Oka Academy – even more so this year as it marks an important anniversary for the school. Stage manager Kaori (Miho Miyazawa) has come in extra early to prep for the performance, but also because she’s enjoying a covert assignation with her boyfriend whom she is keen to get rid of before anyone else turns up and catches them at it. Hearing the door, Kaori bundles him out the back way before the show’s director, Yuko (Hiroko Nakajima), who is also playing a maid arrives looking a little different – she’s had a giant perm.

Yuko’s hair is very much against school regulations but she figures they’ll get over it. Fortunately or unfortunately, Yuko’s hairdo is the least of their problems. Another girl who is supposed to be playing a leading role, Noriko (Miho Tsumiki), has been caught smoking and hanging out with delinquents from another school. She and her parents are currently in the headmaster’s office, and everyone is suddenly worried. The girls’ teacher, Ms. Satomi (Mai Okamoto), is going in to bat for them but it sounds like the play might be cancelled at the last-minute just because the strict school board don’t think it appropriate to associate themselves with such a disappointing student.

The drama club acts as a kind of safe space for the girls. Oka Academy is, to judge by the decor and uniforms, a fairly high-class place with strict rules and ideas about the way each of the young ladies should look, feel, and act. Their ages differ, but they’re all getting towards the age when they know whether or not those ideas are necessarily ones they wish to follow. As if to bring out the rigid nature of their school life, The Cherry Orchard is preformed every single year (classic plays get funded more easily than modern drama) but at least, as one commentator puts it, Ms. Satomi’s production is one of the most “refreshing” the school has ever seen, perhaps echoing the new-found freedoms these young women are beginning to explore.

Free they are and free they aren’t as the girls find themselves experiencing the usual teenage confusions but also finding the courage to face them. Yuko’s hair was less about self-expression than it was about catching the attention of a crush – not a boy, but a fellow student, Chiyoko (Yasuyo Shirashima). Chiyoko, by contrast is pre-occupied with her leading role in the play. Last year, in a male role, she excelled but Ranevskaya is out of her comfort zone. Tall and slim, Chiyoko has extreme hangups around her own femininity and would rather have taken any other male role than the female lead.

Yuko keeps her crush to herself but unexpectedly bonds with delinquent student Noriko who has correctly guessed the direction of Yuko’s desires. Sensitively probing the issue, using and then retreating from the “lesbian” label, Noriko draws a partial confession from her classmate but it proves a bittersweet experience. Predictably enough, Noriko’s “delinquency” is foregrounded by her own more certain sexuality. Noriko’s crush on the oblivious Yuko looks set to end in heartbreak, though Nakahara is less interested in the salaciousness of a teenage love triangle than the painfulness of unrequited, unspoken love which leaves Noriko hovering on the sidelines – wiser than the other girls, but paying heavily for it.

Chekhov’s play famously ends with the sound of falling trees, heralding the toppling of an era but with a kind of sadness for the destruction of something beautiful which could not be saved. Nakahara’s film ends with cherry blossoms blowing in through an open window in an empty room. The spectre of endings hangs heavily, neatly echoed by Ms. Satomi’s argument to the promise that the play will go ahead next year with the cry that next year these girls will be gone. This is a precious time filled with fun and friendship in which the drama club affords the opportunity to figure things out away from the otherwise strict and conformist school environment. Nakahara films with sympathetic naturalism, staying mainly within the rehearsal room with brief trips to the roof or empty school corridors capturing these late ‘80s teens for all of their natural exuberance and private sorrows.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

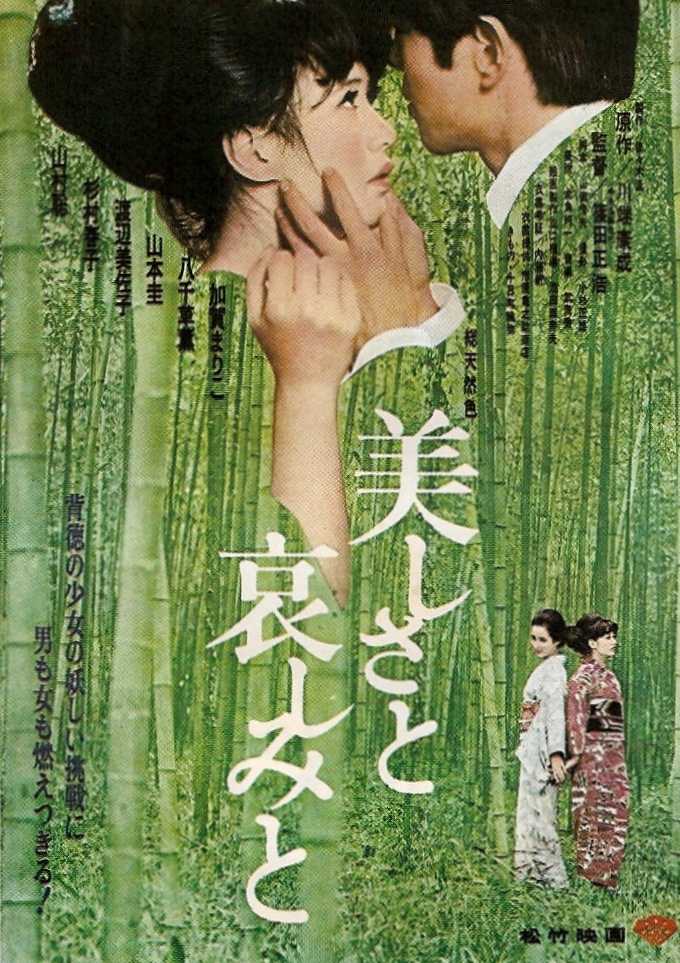

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession.

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession. Following the surreal horror film

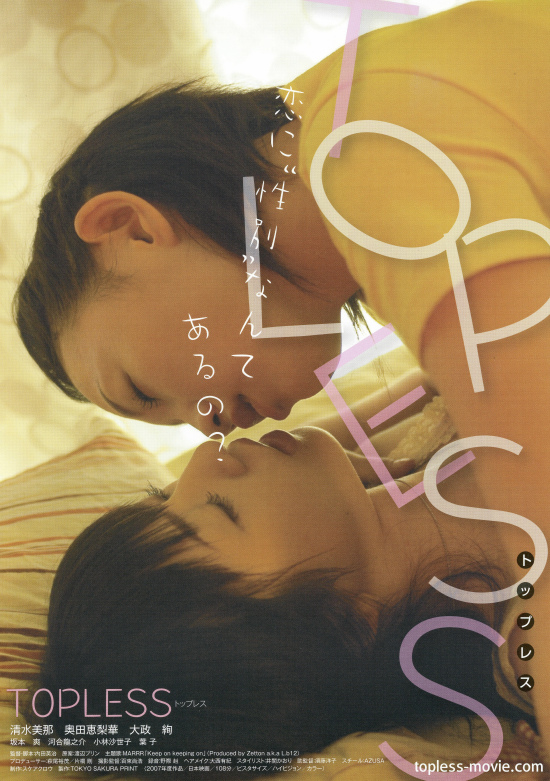

Following the surreal horror film  This area has a weird magnetic field, claims one of the central characters in Takuro Nakamura’s West North West (西北西, Seihokusei), it’ll throw you off course. Barriers to love both cultural and psychological present themselves with almost gleeful melancholy in this indie exploration of directionless youth in modern day Tokyo. Three young women wrestle with themselves and each other in a complex cycle of interconnected anxieties as they attempt to carve out their own paths, each somehow aware of the shape their lives should take yet afraid to pursue it. The Tokyo of West North West is one defined by disconnection, loneliness and permanent anxiety but it is not the city which is the enemy of happiness but an internal unwillingness to find release from self imposed imprisonment.

This area has a weird magnetic field, claims one of the central characters in Takuro Nakamura’s West North West (西北西, Seihokusei), it’ll throw you off course. Barriers to love both cultural and psychological present themselves with almost gleeful melancholy in this indie exploration of directionless youth in modern day Tokyo. Three young women wrestle with themselves and each other in a complex cycle of interconnected anxieties as they attempt to carve out their own paths, each somehow aware of the shape their lives should take yet afraid to pursue it. The Tokyo of West North West is one defined by disconnection, loneliness and permanent anxiety but it is not the city which is the enemy of happiness but an internal unwillingness to find release from self imposed imprisonment. Schoolgirl Complex is a popular photo book featuring the work of Yuki Aoyama and does indeed focus on that most most Japanese of fixations – the school girl and her iconic uniform. Aoyama’s book presents itself as taking the POV of a teenage boy, gazing longly from a position of total innocence at the unattainable female figures who, in the book, are entirely faceless. Given a more concrete narrative, this filmic adaptation (スクールガール コンプレックス 放送部篇, Schoolgirl Complex Housoubu-hen) directed by Yuichi Onuma takes a slightly different tack in dispensing with high school boys altogether for a tale of self discovery and sexual confusion set in an all girls school in which almost everyone has a crush on someone, but sadly finds only adolescent suffering as so eloquently described by Osamu Dazai whose Schoolgirl informs much of the narrative.

Schoolgirl Complex is a popular photo book featuring the work of Yuki Aoyama and does indeed focus on that most most Japanese of fixations – the school girl and her iconic uniform. Aoyama’s book presents itself as taking the POV of a teenage boy, gazing longly from a position of total innocence at the unattainable female figures who, in the book, are entirely faceless. Given a more concrete narrative, this filmic adaptation (スクールガール コンプレックス 放送部篇, Schoolgirl Complex Housoubu-hen) directed by Yuichi Onuma takes a slightly different tack in dispensing with high school boys altogether for a tale of self discovery and sexual confusion set in an all girls school in which almost everyone has a crush on someone, but sadly finds only adolescent suffering as so eloquently described by Osamu Dazai whose Schoolgirl informs much of the narrative.

One of the very earliest films to address female same sex love in Korea, Ashamed (yes, really, but not quite – we’ll get to this later, 창피해, Changpihae, retitled Life is Peachy for US release) had a lot riding on it. Perhaps too much, but does at least manage to outline a convincing, refreshingly ordinary failed love romance even if hampered by a heavy handed structuring device and a lack of chemistry between its leading ladies.

One of the very earliest films to address female same sex love in Korea, Ashamed (yes, really, but not quite – we’ll get to this later, 창피해, Changpihae, retitled Life is Peachy for US release) had a lot riding on it. Perhaps too much, but does at least manage to outline a convincing, refreshingly ordinary failed love romance even if hampered by a heavy handed structuring device and a lack of chemistry between its leading ladies. The history of LGBT cinema in Korea is admittedly thin though recent years have seen an increase in big screen representation with an interest in exploring the reality rather than indulging in stereotypes. The debut feature from Lee Hyun-ju, Our Love Story (연애담, Yeonaedam), is among the first to chart the course of an ordinary romance between two women with all of the everyday drama that modern love entails. A beautiful, bittersweet tale of frustrated connection, Our Love Story is a realistic look at messy first love taking place under the snowy skies of Seoul.

The history of LGBT cinema in Korea is admittedly thin though recent years have seen an increase in big screen representation with an interest in exploring the reality rather than indulging in stereotypes. The debut feature from Lee Hyun-ju, Our Love Story (연애담, Yeonaedam), is among the first to chart the course of an ordinary romance between two women with all of the everyday drama that modern love entails. A beautiful, bittersweet tale of frustrated connection, Our Love Story is a realistic look at messy first love taking place under the snowy skies of Seoul.

“Being naked in front of people is embarrassing” says the drunken mother of a recently deceased major character in a bizarre yet pivotal scene towards the end of Shunji Iwai’s aptly titled A Bride for Rip Van Winkle (リップヴァンウィンクルの花嫁, Rip Van Winkle no Hanayome) in which the director himself wakes up from an extended cinematic slumber to discover that much is changed. This sequence, in a sense, makes plain one of the film’s essential themes – truth, and the appearance of truth, as mediated by human connection. The film’s timid heroine, Nanami (Haru Kuroki), bares all of herself online, recording each ugly thought and despairing notion before an audience of anonymous strangers, yet can barely look even those she knows well in the eye. Though Namami’s fear and insecurity are painfully obvious to all, not least to herself, she’s not alone in her fear of emotional nakedness as she discovers throughout her strange odyssey in which nothing is quite as it seems.

“Being naked in front of people is embarrassing” says the drunken mother of a recently deceased major character in a bizarre yet pivotal scene towards the end of Shunji Iwai’s aptly titled A Bride for Rip Van Winkle (リップヴァンウィンクルの花嫁, Rip Van Winkle no Hanayome) in which the director himself wakes up from an extended cinematic slumber to discover that much is changed. This sequence, in a sense, makes plain one of the film’s essential themes – truth, and the appearance of truth, as mediated by human connection. The film’s timid heroine, Nanami (Haru Kuroki), bares all of herself online, recording each ugly thought and despairing notion before an audience of anonymous strangers, yet can barely look even those she knows well in the eye. Though Namami’s fear and insecurity are painfully obvious to all, not least to herself, she’s not alone in her fear of emotional nakedness as she discovers throughout her strange odyssey in which nothing is quite as it seems. Growing up is hard to do. So it is for the teenage protagonists of Hiroshi Ando’s debut mainstream feature, Blue (ブルー), adapted from the manga by Kiriko Nananan. Like Nananan’s original comic, the cinematic adaptation of Blue is refreshingly angst free in its examination of first love and the burgeoning sexuality of two lonely high school girls. Shot with a chilly stillness which echoes the emptiness of this small town existence, Blue is no nostalgic retreat into cosy teenage dreams but a cold hard look at the messiness and pain of adolescent love.

Growing up is hard to do. So it is for the teenage protagonists of Hiroshi Ando’s debut mainstream feature, Blue (ブルー), adapted from the manga by Kiriko Nananan. Like Nananan’s original comic, the cinematic adaptation of Blue is refreshingly angst free in its examination of first love and the burgeoning sexuality of two lonely high school girls. Shot with a chilly stillness which echoes the emptiness of this small town existence, Blue is no nostalgic retreat into cosy teenage dreams but a cold hard look at the messiness and pain of adolescent love.