According to the title card at the beginning of Shigehiro Ozawa’s Killer’s Mission (賞金稼ぎ, Shokin Kasegi), none of the events it depicts have been recorded in history because the shogunate decided to erase them all in fear of the effect they may have on the nation’s geopolitical stability. Nevertheless, it gives some very concrete dates for its historical action, even if they may not make complete sense while foreshadowing the political turbulence of the following century.

What it essentially attempts to do is tell a James Bond-style tale of political intrigue in a feudal Japan in which perpetual peace has begun to create its own problems. Here played in a cameo appearance from Koji Tsuruta, the Shogun Ieshige was weak in part because he was in poor health and had a speech impediment which led him to be rejected by his retainers. The problem here, however, is with Satsuma which has been on bad terms with the Tokugawa shogunate since the Battle of Sekigahara after which they took power. Satsuma will in fact be at the centre of the conspiracy to overthrow the government in the following century, but for the purposes of the film have fallen foul of a rumour that the plan to do an arms deal with some Dutch sailors who sailed South to Kyushu after being rebuffed in Edo.

A civil war is feared and in the interests of maintaining peace, Ieshige sends his trusted spy Ichibei (Tomisaburo Wakayama) to protect Satsuma official Ijuin Ukiyo (Chiezo Kataoka) in the hope that he will be able to talk his young and naive lord out of doing the deal. Ostensibly a doctor by trade, Ichibei has a series of spy gadgets such as hidden blades and collapsible guns stored in a secret room at his surgery which he then carries in a black leather utility belt. He keeps the nature of his mission close to his chest, but often double bluffs by simply telling people he is a shogunate spy or otherwise adopting a disguise as he does in a moment of meta comedy impersonating the signature role of his brother Shintaro Katsu by posing as a Zatoichi-style blind masseur.

As if to signal the cruelty of the feudal world, Ichibei comes across the corpses of suspected spies abandoned outside Satsuma territory while his enemies meditate on their ancient slight and consider taking the deal in the hope of avenging their defeat and overthrowing the Tokugawa. They are warned that creating unrest and sowing division may be exactly what foreign powers like the Dutch crave, but aren’t particularly bothered, preferring to take their chances with them rather than curry favour with the Shogun and possibly destabilising the entire society along with it.

Of course, much of this is anachronistic with the Dutch sailors appearing in a distinctly 19th century fashion carrying weapons which are also too advanced for the era as are Ichibei’s folding pistols. Through his travels, he runs into a female Iga spy who too can do some nifty ninja tricks and has a gadget of her own in a comb which can shoot poison darts, though luckily it’s one of the poisons Ichibei has already developed an immunity to. Ichibei is fond of crying that you kill him he’ll simply come back to life, barrelling through the air with feats of improbable human agility and generally behaving like some kind of supernatural entity with a secondary talent for violent seduction.

Though ironic and often darkly comic, there is an unavoidable poignancy in the inner conflict of Ijuin who knows his clan is about to do something very foolish but is torn between his duty to obey them and that to act in their best interests, eventually backed into a corner and left with no real way out of his predicament. As Ichibei points out, it’s difficult to keep the peace, especially when restless young samurai spot opportunities to cause chaos and the outside world knocks on the door of a closed community. Even so, Ozawa ends on a romantic image of a beach at sunset somehow undercutting the violence and tragedy with the restoration of an order that might itself be imperfect in its peacefulness.

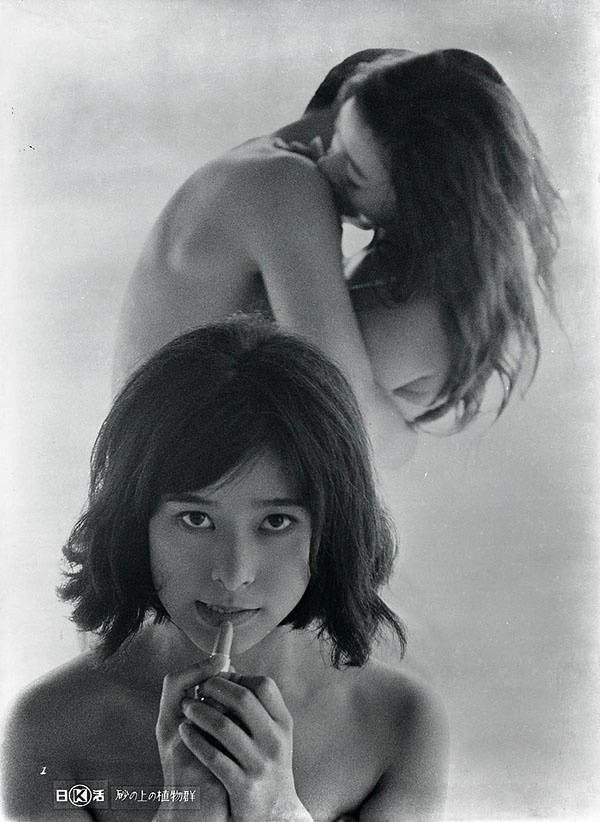

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.

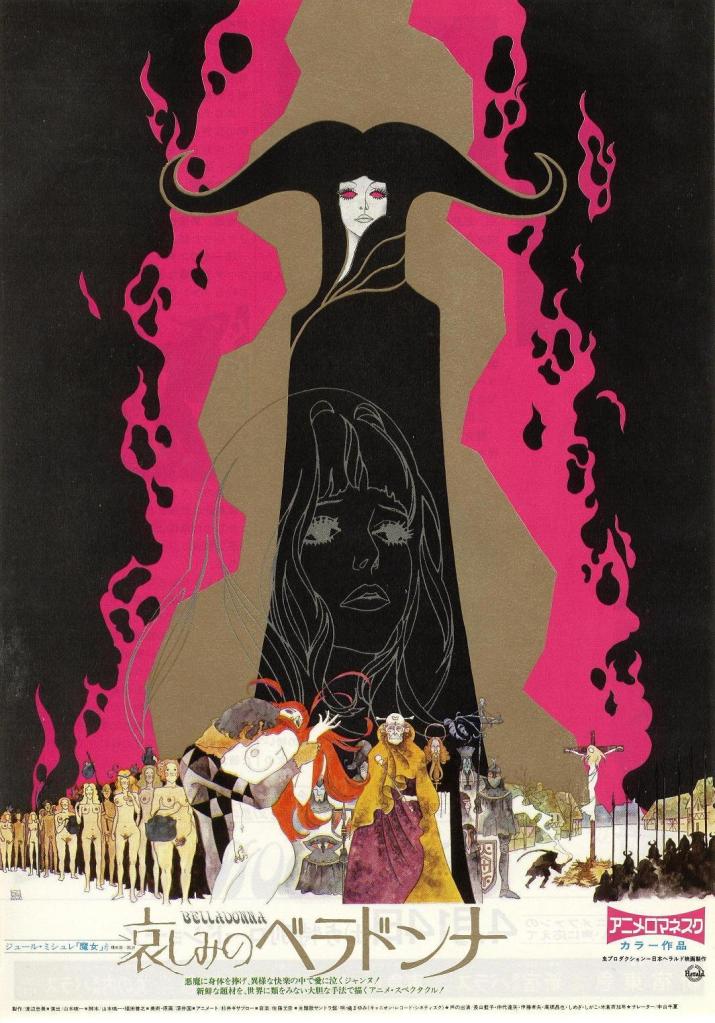

Loosely based on Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (Satanism and Witchcraft) which reframed the idea of the witch as a revolutionary opposition to the oppression of the feudalistic system and the intense religiosity of the Catholic church, Belladonna of Sadness (哀しみのベラドンナ, Kanashimi no Belladonna) was, shall we say, under appreciated at the time of its original release even being credited with the eventual bankruptcy of its production studio. Begun as the third in the Animerama trilogy of adult orientated animations produced by legendary manga artist Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Productions, Belladonna of Sadness is the only one of the three with which Tezuka was not directly involved owing to having left the company to return to manga. Consequently the animation sheds his characteristic character designs for something more akin to Art Nouveau elegance mixed with countercultural psychedelia and pink film compositions. Feminist rape revenge fairytale or an exploitative exploration of the “demonic” nature of female sexuality and empowerment, Belladonna of Sadness is not an easily forgettable experience.

Loosely based on Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (Satanism and Witchcraft) which reframed the idea of the witch as a revolutionary opposition to the oppression of the feudalistic system and the intense religiosity of the Catholic church, Belladonna of Sadness (哀しみのベラドンナ, Kanashimi no Belladonna) was, shall we say, under appreciated at the time of its original release even being credited with the eventual bankruptcy of its production studio. Begun as the third in the Animerama trilogy of adult orientated animations produced by legendary manga artist Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Productions, Belladonna of Sadness is the only one of the three with which Tezuka was not directly involved owing to having left the company to return to manga. Consequently the animation sheds his characteristic character designs for something more akin to Art Nouveau elegance mixed with countercultural psychedelia and pink film compositions. Feminist rape revenge fairytale or an exploitative exploration of the “demonic” nature of female sexuality and empowerment, Belladonna of Sadness is not an easily forgettable experience.