Yakuza aren’t supposed to be funny, are they? According to one particular lover of Lepidoptera, that’s all they ever need to be. Scripted by Kankuro Kudo and adapted from the manga by Noboru Takahashi, Takashi Miike’s The Mole Song: Undercover Agent Reiji (土竜の唄 潜入捜査官 REIJI, Mogura no Uta: Sennyu Sosakan Reiji) is the classic bad spy comedy in which a hapless beat cop is dragged out of his police box and into the field as a yakuza mole in the (rather ambitious) hope of ridding Japan of drugs. As might be assumed, Reiji’s quest does not quite go to plan but then in another sense it goes better than anyone might have hoped.

Yakuza aren’t supposed to be funny, are they? According to one particular lover of Lepidoptera, that’s all they ever need to be. Scripted by Kankuro Kudo and adapted from the manga by Noboru Takahashi, Takashi Miike’s The Mole Song: Undercover Agent Reiji (土竜の唄 潜入捜査官 REIJI, Mogura no Uta: Sennyu Sosakan Reiji) is the classic bad spy comedy in which a hapless beat cop is dragged out of his police box and into the field as a yakuza mole in the (rather ambitious) hope of ridding Japan of drugs. As might be assumed, Reiji’s quest does not quite go to plan but then in another sense it goes better than anyone might have hoped.

Reiji Kikukawa (Toma Ikuta) is, to put it bluntly, not the finest recruit the Japanese police force has ever received. He does, however, have a strong sense of justice even if it doesn’t quite tally with that laid down in law though his methods of application are sometimes questionable. A self-confessed “pervert” (but not a “twisted” one) Reiji is currently in trouble for pulling his gun on a store owner who was extracting sexual favours from high school girls he caught shop lifting (the accused is a city counsellor who has pulled a few strings to ask for Reiji’s badge). Seizing this opportunity, Reiji’s boss (Mitsuru Fukikoshi) has decided that he’s a perfect fit for a spell undercover in a local gang they suspect of colluding with Russian mafia to smuggle large amounts of MDMA into Japan.

Reiji hates drugs, but not as much as his new best buddy “Crazy Papillon” (Shinichi Tsutsumi) who is obsessed with butterflies and insists everything that happens around him be “funny”. Reiji, an idiot, is very funny indeed and so he instantly gets himself a leg up in the yakuza world whilst forming an unexpectedly genuine bond with his new buddy who also really hates drugs and only agreed to join this gang because they promised him they didn’t have anything to with them.

Sliding into his regular manga mode, Miike adopts his Crows Zero aesthetic but re-ups the camp as Reiji gets fired up on justice and takes down rooms full of punks powered only by righteousness and his giant yakuza hairdo. Like most yakuza movies, the emphasis is on the bonds between men and it is indeed the strange connection between Reiji and Papillon which takes centerstage as Miike milks the melodrama for all it’s worth.

Scripted by Kankuro Kudo (who previously worked with the director on the Zebra Man series), Reiji skews towards a slightly different breed of absurdity from Miike’s patented brand but retains the outrageous production design including the big hair, garish outfits, and carefully considered colour scheme. Mixing amusing semi-animated sequences with over the top action and the frequent reoccurrence of the “Mole Song”, Miike is in full-on sugar rush mode, barely pausing before moving on from one ridiculous set piece to the next.

Ridiculous set pieces are however the highlight of the film from Reiji’s early series of initiation tests to his attempts to win the affections of his lady love, Junna (Riisa Naka), and a lengthy sojourn at a mysterious yakuza ceremony which Reiji manages to completely derail through a series of misunderstandings. At 130 minutes however, it’s all wearing a bit thin even with the plot machinations suddenly kicking into gear two thirds of the way through. Nevertheless, there’s enough silly slapstick comedy and impressive design work at play to keep things interesting even if Reiji’s eventual triumph is all but guaranteed.

Screened as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2018.

Screening again:

- Queen’s Film Theatre – 21 February 2018

- Phoenix Leicester – 24 February 2018

- Brewery Arts Centre – 16 March 2018

- Broadway – 20 March 2018

- Midlands Arts Centre – 27 March 2018

- Showroom Cinema – 28 March 2018

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Like many fillmakers of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began directing commercially in the 1980s working in the pink genre but it was the early ‘90s straight to video boom which provided a career breakthrough. This relatively short lived movement was built on speed where the reliability of the familiar could be harnessed to produce and market low budget genre films with a necessarily high turnover. Kurosawa made his first foray into the V-cinema world in 1994 with the unlikely comedy vehicle Yakuza Taxi (893 タクシー, 893 Taxi). Although Kurosawa had originally accepted the project in the hope of being able to direct a large scale action film, his distaste for the company’s insistence on “jingi” (the yakuza code of honour and humanity) proved something of a barrier but it did, at least, lend free rein to the director’s rather ironic sense of humour.

Like many fillmakers of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began directing commercially in the 1980s working in the pink genre but it was the early ‘90s straight to video boom which provided a career breakthrough. This relatively short lived movement was built on speed where the reliability of the familiar could be harnessed to produce and market low budget genre films with a necessarily high turnover. Kurosawa made his first foray into the V-cinema world in 1994 with the unlikely comedy vehicle Yakuza Taxi (893 タクシー, 893 Taxi). Although Kurosawa had originally accepted the project in the hope of being able to direct a large scale action film, his distaste for the company’s insistence on “jingi” (the yakuza code of honour and humanity) proved something of a barrier but it did, at least, lend free rein to the director’s rather ironic sense of humour. Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way.

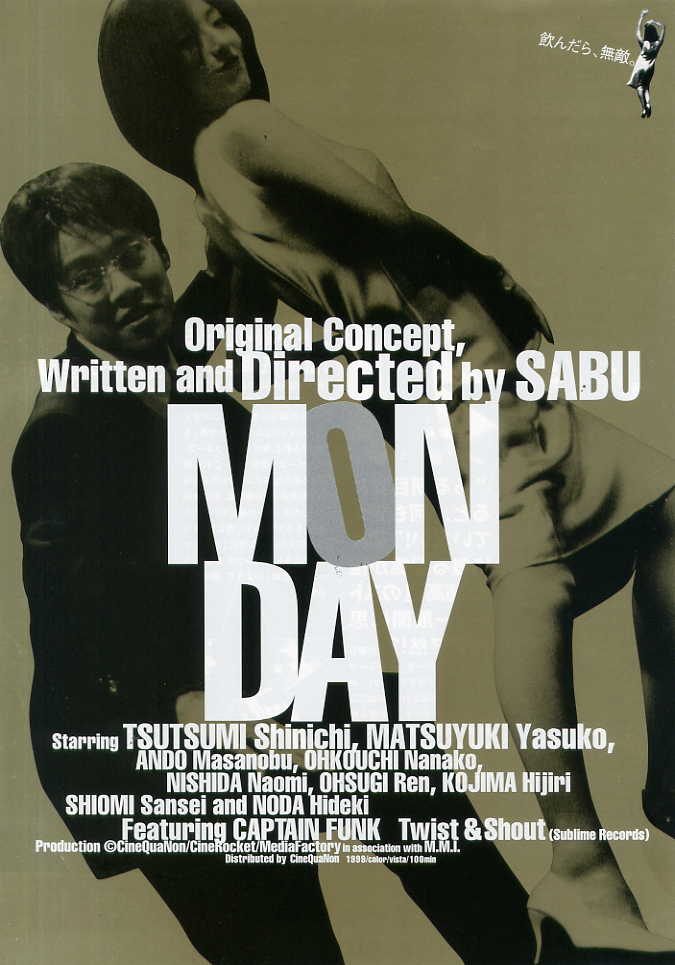

Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way. In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not.

In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not. Review of Kitano’s Kids Return first published by

Review of Kitano’s Kids Return first published by  Review of Takeshi Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea – first published by

Review of Takeshi Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea – first published by  Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.