“We don’t resort to violence. We observe the law.’ The hero of Kinji Fukasaku’s Yakuza Graveyard (やくざの墓場 くちなしの花, Yakuza no Hakaba: Kuchinashi no Hana) is berated by a superior officer for excessive use of force, but his criticism is in some senses ironic because it is the police force itself which becomes a symbol of the societal violence visited on those who can find no place to belong in the contemporary society. By this time the yakuza was already in decline and in the process of transforming itself into a corporatised entity while as a police chief explains increasing desperation has led to escalating gang tensions.

Recently transferred maverick cop Kuroiwa (Tetsuya Watari) finds himself caught between two worlds in attempting to enforce the law through methods more familiar to yakuza. Soon after he’s had his gun taken away for exercising excessive force on a suspect he’d been independently tailing in the street on whom he’d found bullets designed to be used with a remodelled toy gun, Kuroiwa is pulled aside by another senior officer, Akama (Nobuo Kaneko) who takes him to a meeting with local yakuza boss Sugi (Takuya Fujioka). It seems obvious that Akama has cultivated a relationship with the Nishida gang which may not be strictly ethical for a law enforcement officer and hopes to bring Kuroiwa on board as a potential asset. They attempt to bribe him in return for information on the Yamashiro clan, the dominant organised crime association in the area, which has been hassling Nishida in an attempt to take over their territory. But Kuroiwa ironically tells them that they should “act like yakuza” and sort out their own problems rather than relying on the police before dramatically walking out much to to the consternation of everyone else present.

Nevertheless, he eventually comes to sympathise with them as a symbol of the little guy increasingly crushed by corporate and authoritarian forces outside of their control. He finds out from a briefing that the police’s goal is the disbandment of the Nishida gang but when he asks why they aren’t going after the Yamashiro too he’s told to mind his own business and begins to realise that the police are in cahoots with organised crime. Whether they justify themselves that managing the Yamashiro to prevent a turf war is the best way to protect the public or are simply corrupt and in the pocket of big business, Kuroiwa can’t help but balk at the blatant hypocrisy of the law enforcement authorities.

Later Kuroiwa reveals that he became a police officer after being bullied as a child in order to exert power over his life, or perhaps becoming an oppressor in order to avoid being oppressed. He was bullied because he had been born in Manchuria and even years later remains a displaced person at least on a psychological level. It’s this sense of displacement which allows him to bond with the Nishida gang’s accountant, Keiko (Meiko Kaji), whose father was Korean. Kuroiwa agrees to accompany Keiko to visit her husband (Kenji Imai) who is serving a lengthy prison term in order to tell him that the gang want to promote someone else to a position he viewed as his by right. The husband explodes in rage and uses a word some would regard as a slur to reference Keiko’s Korean heritage while she later attempts to walk into the sea feeling that there really is no place for her in the contemporary society.

Just as she claims that she is neither Korean nor Japanese or much of anything at all, Kuroiwa is neither cop nor thug and similarly excluded from society at large. He ends up bonding with old school Nishida footsoldier Iwata (Tatsuo Umemiya), who is also ethnically Korean, for many of the same reasons and attempts to mount a doomed rebellion against their mutual oppression, but is hamstrung by his otherness which is only deepened when he’s taken prisoner by loan shark Teramitsu (Kei Sato) and given a mysterious truth drug developed by the nazis later becoming a user of heroin. Already marginalised, forced into crime by economic necessity and social prejudice, Iwata and Keiko like Kuroiwa himself struggle to escape their displacement while pushed still further out by systemic corruption and the amoral capitalism of an era of high prosperity. Shot with jitsuroku-esque realism and characteristically canted angles, Fukasaku injects a note of futility even within the hero’s tragic victory as he quite literally sticks two fingers up to the corrupted “brotherhood” that has already betrayed him.

Yakuza Graveyard is released on blu-ray on 16th May courtesy of Radiance Films. On disc extras include an in-depth appreciation of the film and the work of screenwriter Kazuo Kasahara from Blood of Wolves director Kazuya Shiraishi, and an informative video essay from Tom Mes on the collaborations of Meiko Kaji and Kinji Fukasaku. The limited edition also comes with a 32-page booklet featuring new writing by Miko Ko plus translations of a contemporary review and writing by Kasahara.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Robbing a bank is harder than it looks but if it does all go very wrong, escaping by bus is not an ideal solution. Sadao Nakajima is best known for his gritty yakuza movies but Kurutta Yaju ( 狂った野獣, Crazed Beast/Savage Beast Goes Mad) takes him in a slightly different direction with its strangely comic tale of bus hijacking, counter hijacking, inept police, and fretting mothers. If it can go wrong it will go wrong, and for a busload of people in Kyoto one sunny morning, it’s going to be a very strange day indeed.

Robbing a bank is harder than it looks but if it does all go very wrong, escaping by bus is not an ideal solution. Sadao Nakajima is best known for his gritty yakuza movies but Kurutta Yaju ( 狂った野獣, Crazed Beast/Savage Beast Goes Mad) takes him in a slightly different direction with its strangely comic tale of bus hijacking, counter hijacking, inept police, and fretting mothers. If it can go wrong it will go wrong, and for a busload of people in Kyoto one sunny morning, it’s going to be a very strange day indeed. All things considered, a live pig is a rather insensitive gift to present to your local police station, though any gift at all might be considered in appropriate even if offered by a well meaning colleague keen to help out when a horrific murder may be connected to his missing person case. By 1977 Kinji Fukasaku had made a name for himself through the wildly successful “jitsuroku” or “true record” genre of yakuza movies kickstarted by his own

All things considered, a live pig is a rather insensitive gift to present to your local police station, though any gift at all might be considered in appropriate even if offered by a well meaning colleague keen to help out when a horrific murder may be connected to his missing person case. By 1977 Kinji Fukasaku had made a name for himself through the wildly successful “jitsuroku” or “true record” genre of yakuza movies kickstarted by his own  Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first  Hideo Gosha had something of a turbulent career, beginning with a series of films about male chivalry and the way that men work out all their personal issues through violence, but owing to the changing nature of cinematic tastes, he found himself at a loose end towards the end of the ‘70s. Things picked up for him in the ‘80s but the altered times brought with them a slightly different approach as Gosha’s films took on an increasingly female focus in which he reflected on how the themes he explored so fully with his male characters might also affect women. In part prompted by his divorce which apparently gave him the view that women were just as capable of deviousness as men are, and by a renewed relationship with his daughter, Gosha overcame the problem of his chanbara stars ageing beyond his demands of them by allowing his actresses to lead.

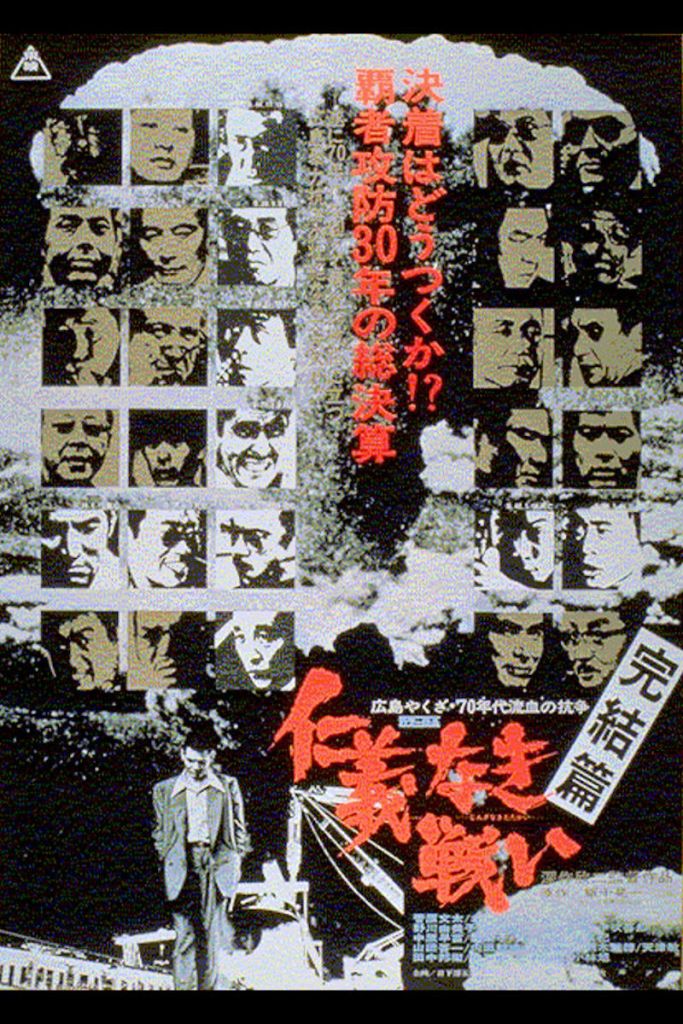

Hideo Gosha had something of a turbulent career, beginning with a series of films about male chivalry and the way that men work out all their personal issues through violence, but owing to the changing nature of cinematic tastes, he found himself at a loose end towards the end of the ‘70s. Things picked up for him in the ‘80s but the altered times brought with them a slightly different approach as Gosha’s films took on an increasingly female focus in which he reflected on how the themes he explored so fully with his male characters might also affect women. In part prompted by his divorce which apparently gave him the view that women were just as capable of deviousness as men are, and by a renewed relationship with his daughter, Gosha overcame the problem of his chanbara stars ageing beyond his demands of them by allowing his actresses to lead. And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best.

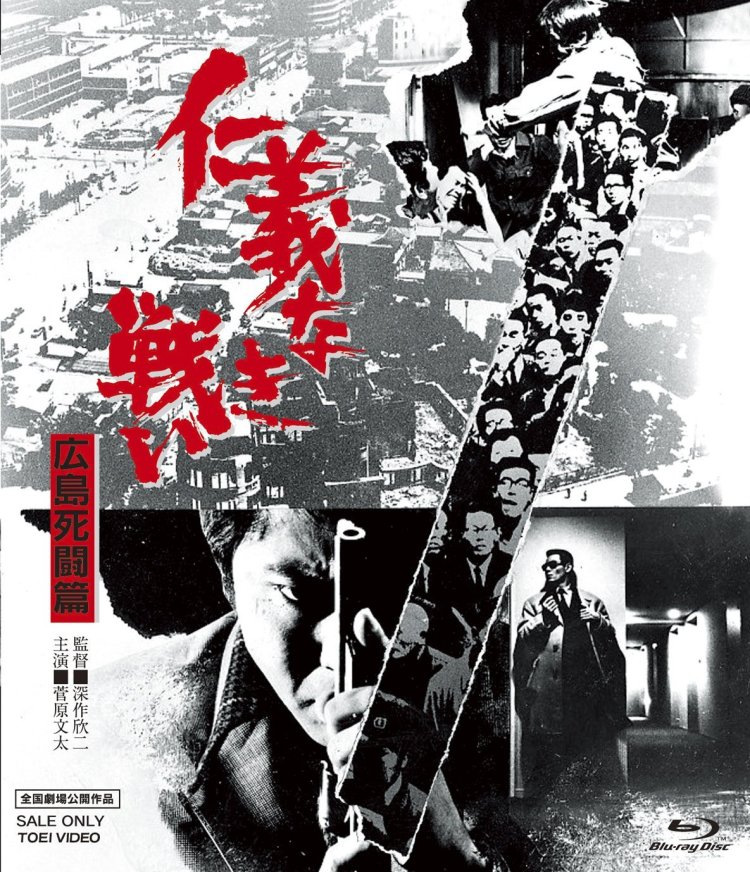

And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best. Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.

Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly. If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of

If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of