Japan was rocked by scandal in 1976 when it came to light that American aviation firm Lockheed had paid the office of then Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka three million dollars funnelled through right-wing fixer Yoshio Kodama to ensure that Japanese airlines such as ANA purchased Lockheed Lockheed L-1011 TriStar passenger jets rather than the McDonnell Douglas DC-10. The disturbing revelations deepened a sense of mistrust in the government which was shown to be inherently corrupt and in constant collusion with nationalist activists and yakuza.

This might be why the figure of the political mastermind hangs heavy over the Japanese paranoia cinema of the 1970s. The Fixer (日本の黒幕 Nihon no Fixer), however, rather ironically began as a vehicle for director Nagisa Oshima. At that time, Toei was struggling as its run of jitsuroku movies began to run out of steam. Producer Goro Kusakabe wanted to make a film about Kodama, who’d been alluded to in the Japanese Godfather series, and thought that getting Oshima to do it would take Toei in a new artistic direction, moving them away from the studio model by bringing in outside auteurist talent. But the problem with that was that an artist like Oshima did not want to work with a typical studio production model and, at the end of the day, what Toei wanted was a commercial film. It also has to be said that as a studio Toei tended to lean towards the right, and the film that was finally produced, directed by action drama specialist Yasuo Furuhata using a script by Koji Takada which Oshima had described as “boring”, was much more sympathetic towards its subject than Oshima would likely have been.

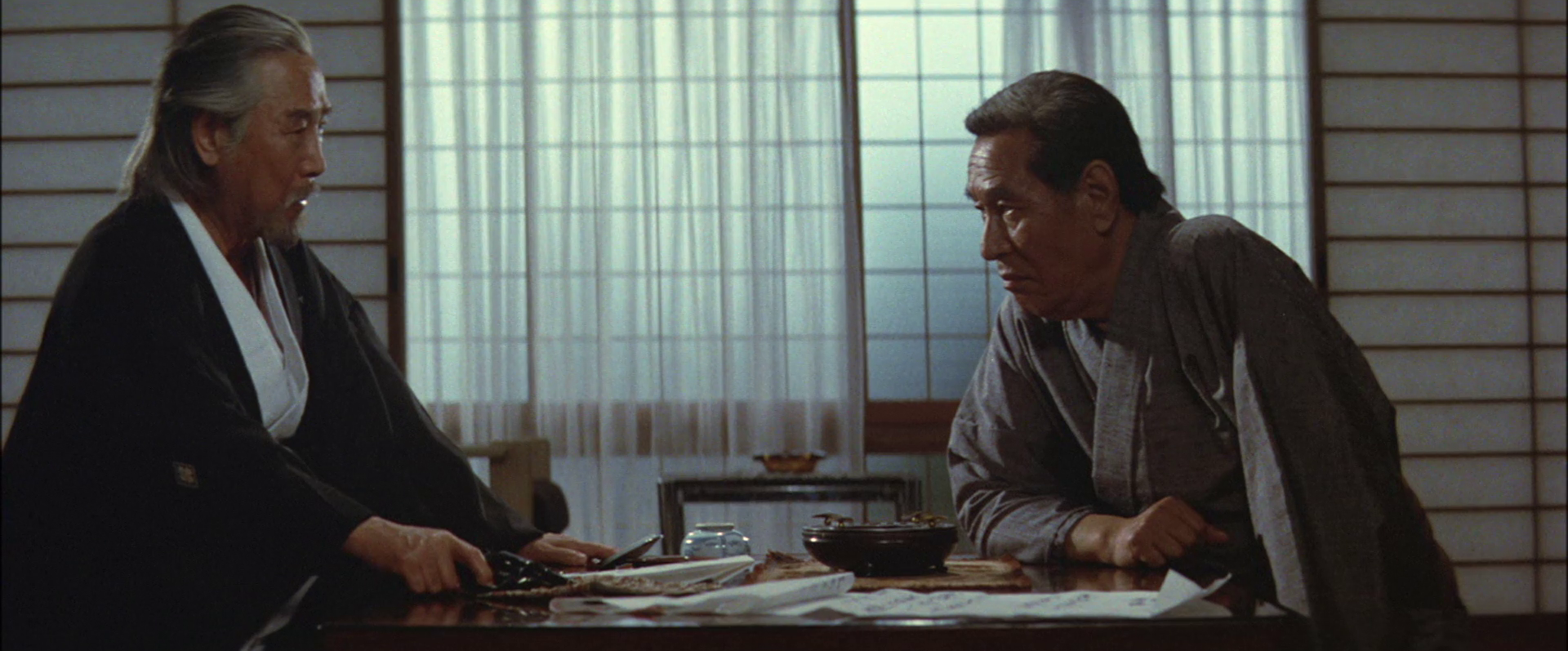

Like the Japanese Godfather, series it’s essentially a Greek tragedy retold as yakuza movie in which Kodama is brought low by a series of betrayals that prevent him realising his dream of an ideal Japan, which in effect means undoing democracy to restore the pre-war militarist regime. The true source of the corruption is then shifted to the prime minister, Hirayama (Ryunosuke Kaneda), a stand-in for Tanaka, who is brought to power by Yamaoka (Shin Saburi), a thinly veiled Kodama, but later betrays him for a shot at a political comeback following a bribery scandal during which Yamaoka is left out to dry. Yamaoka casts himself as the true patriot, and Hirayama as the greedy opportunist who only cares about his own wealth and status.

Yamaoka’s vision of himself is eventually undercut by a former ally who accuses him of being deluded by his own lust for power, placing a pistol on the table in front of him and suggesting he do the honourable thing. Yamaoka, however, does not want to do that and gives a last speech to his young men explaining that silence is his way of fighting back and that he’ll be vindicated in the end, which he eventually is when Hirayama is arrested. The drama is played out in part by the internal conflict within a young man with a bad leg who first tries to assassinate Yamaoka but is taken in by him and trained up as a potential successor only to be manipulated by his daughter who hands him the dagger Hirayama had returned to Yamaoka when he betrayed him and asks whether he wants to kill a woman or the “real villain”, by which she means Yamaoka but the boy has a different target in mind.

On the other hand, Yamaoka is exposed as having some very weird and cult-like ideas such as breeding a child that has his completely purified blood in his veins by encouraging a relationship between his legitimate daughter and a young man he brought back from China she has no idea is her half-brother born to a Chinese woman Yamaoka murdered to escape Manchuria. Brief mentions are made of Yamaoka’s Manchurian exploits though painted in a more heroic fashion that Kodama’s reality, as in a late speech about how “terrorism” has lost its meaning as some of the young men joining Yamaoka’s militia meditate on his pre-war activities in which he belonged to an organisation that assassinated politicians who advocated for peaceful coexistence with Korea and China.

That the young assassin, Ikko (Tsutomu Kariba), eventually decides to knife Hirayama as the “real” villain, suggests that the youth of Japan has chosen Yamaoka rather than simply being sick of the political corruption he in effect represents even as others quickly, and perhaps uncritically, leap to his defence buying his claims of having been targeted due to “internal infighting”. While those around him are driven towards their deaths, Yamaoka survives muttering that it’s all for Japan even while finding himself cut loose as rival yakuza factions vie over territory and political influence. Lighting candles at his altar, it’s almost as if these men are human sacrifices designed to bring about his vision of a “better” Japan and chillingly it seems he has no shortage of willing victims.

Trailer (no subtitles)