Yoshihiro Nakamura has made a name for himself as a master of fiendishly intricate, warm and quirky mysteries in which seemingly random events each radiate out from a single interconnected focus point. Golden Slumber (ゴールデンスランバー), like The Foreign Duck, the Native Duck and God in a Coin Locker, and Fish Story, is based on a novel by Kotaro Isaka and shares something of the same structure but is far less interested in the mystery itself rather than the man who finds himself caught up in it.

Yoshihiro Nakamura has made a name for himself as a master of fiendishly intricate, warm and quirky mysteries in which seemingly random events each radiate out from a single interconnected focus point. Golden Slumber (ゴールデンスランバー), like The Foreign Duck, the Native Duck and God in a Coin Locker, and Fish Story, is based on a novel by Kotaro Isaka and shares something of the same structure but is far less interested in the mystery itself rather than the man who finds himself caught up in it.

30 year old delivery driver Aoyagi (Masato Sakai) is all set for a nice day out fishing with an old college buddy, Morita (Hidetaka Yoshioka), but he’s about to discover that it’s he’s been hooked and reeled in as the patsy in someone else’s elaborate assassination plot. After grabbing some fast food, Morita takes Aoyagi to a parked car near the closed off area through which the Prime Minster is due to be paraded in an open topped car. Waking up after a brief period of drug induced sedation, Aoyagi is made aware that this has all been a trick – badly in debt thanks to his wife’s pachinko addiction, Morita has betrayed him to a set of undisclosed bad guys with unclear motives and is taking this brief opportunity to give him as much warning as he can. Sure enough, a bomb goes off at the parade and Aoyagi just manages to escape before Morita too is the victim of an explosion.

Aoyagi is now very confused and on the run. Inexplicably, the police seem to have CCTV footage of him in places he’s never been and doing things he’s never done. If he’s going to survive any of this, he’s going to need some help but caught between old friends and new, trust has just become his most valuable commodity.

At heart, Golden Slumber is a classic Wrong Man narrative yet it refuses to follow the well trodden formula in that it isn’t so much interested in restoring the protagonist to his former life unblemished as it is in giving him a new one. The well known Beatles song Golden Slumber which runs throughout the film plays into its neatly nostalgic atmosphere as each of the now 30 year old college friends find themselves looking back into those care free, joyous days before of the enormity of their adult responsibilities took hold. That is to say, aside from Aoyagi himself who seems to have been muddling along amiably before all of this happened to him, unmarried and working a dead end delivery job.

As Morita tells him in the car, it’s all about image. The nature of the conspiracy and the identity of the perpetrators is not the main the main thrust of the film, but the only possible motive suggested for why Aoyagi has been chosen stems back to his unexpected fifteen minutes of fame two years previously when he saved a pop idol from an intruder with a nifty judo move (taught to him by Morita in uni) after fortuitously arriving with a delivery. Those behind the conspiracy intend to harness his still vaguely current profile to grab even more media attention with a local hero turned national villain spin. The Prime Minister, it seems, was a constantly controversial, extreme right wing demagogue with a tendency for making off the cuff offensive statements so there are those who’d rather congratulate Aoyagi than bring him to justice, but anyone who’s ever met him knows none of this can really be true despite the overwhelming video evidence.

Throughout his long odyssey looking for “the way back home” as the song puts it, Aoyagi begins to remember relevant episodes from his life which may feed back into his current circumstances. Although it seems as if Aoyagi had not seen Morita in some time (he knew nothing of his family circumstances, for example) his college friends with whom he wasted time “reviewing” junk food restaurants and chatting about conspiracy theories are still the most important people in his life. Not least among them is former girlfriend Haruko (Yuko Takeuchi), now married and the mother of a little daughter, who seems to still be carrying a torch for her old flame and is willing to go to great lengths to help him in his current predicament.

The film seems mixed on whether these hazy college days are the “golden slumber”, a beautiful dream time enhanced by memory to which it is not possible to return, or whether it refers to Aoyagi’s post college life which impinges on the narrative only slightly when he asks an unreliable colleague for help, aside from an accidental moment of heroic celebrity. It could even refer to the film’s conclusion which, departing from the genre norms, resolves almost nothing save for the hero’s neat evasion of the trap (aided by the vexed conspirators who eventually opt for a plan B). Once there might have been a road home – a way back to the past and the renewing of old friendships, but this road seems closed now, severed by the new beginning promised to Aoyagi who has been robbed of his entire identity and all but the memory of his past. Whether this means that the golden slumber has ended and Aoyagi, along with each of the other nostalgia bound protagonists, must now wake up and start living the life he’s been given, or that the old Aoyagi has been consigned to the realm of golden slumbers, may be a matter for debate.

Though the resolution may appear ultimately unsatisfying, the preceding events provide just enough interconnected absurdity to guide it through. During his long journey, Aoyagi is aided not just by his old friends but new ones too including a very strange young serial killer (Gaku Hamada) and a hospital malingerer with one foot in the “underworld” (Akira Emoto). It speaks to Aoyagi’s character that all of those who know him trust him implicitly and are ready to help without even being asked (even if they occasionally waver under pressure), and even those who are meeting him for the first time are compelled to come to his defence. An elliptical, roundabout tale of the weight of nostalgia and inescapability of regret, Golden Slumber is the story of a man on the run from his future which eventually becomes a net he cannot escape.

Original trailer (English subtitles – select via menu)

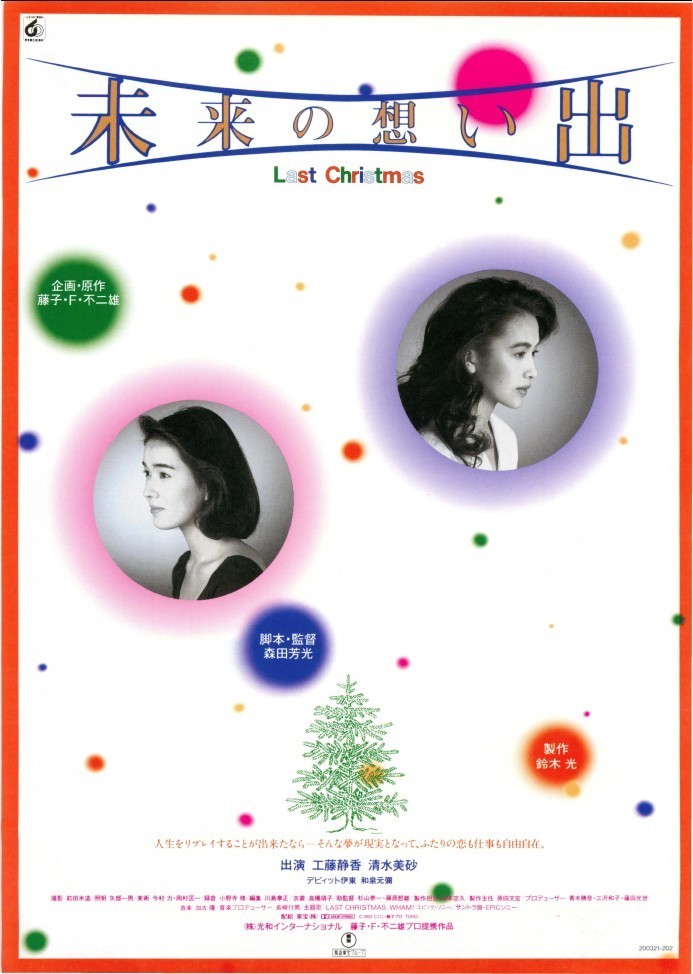

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era. “Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period.

“Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period. When

When

When it comes to tragic romances, no one does them better than Japan. Adapted from a best selling novel by Takuji Ichikawa, Be With You (いま、会いにゆきます, Ima, ai ni Yukimasu) is very much part of the “Jun-ai” or “pure love” boom kickstarted by

When it comes to tragic romances, no one does them better than Japan. Adapted from a best selling novel by Takuji Ichikawa, Be With You (いま、会いにゆきます, Ima, ai ni Yukimasu) is very much part of the “Jun-ai” or “pure love” boom kickstarted by

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate.

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate.

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process.

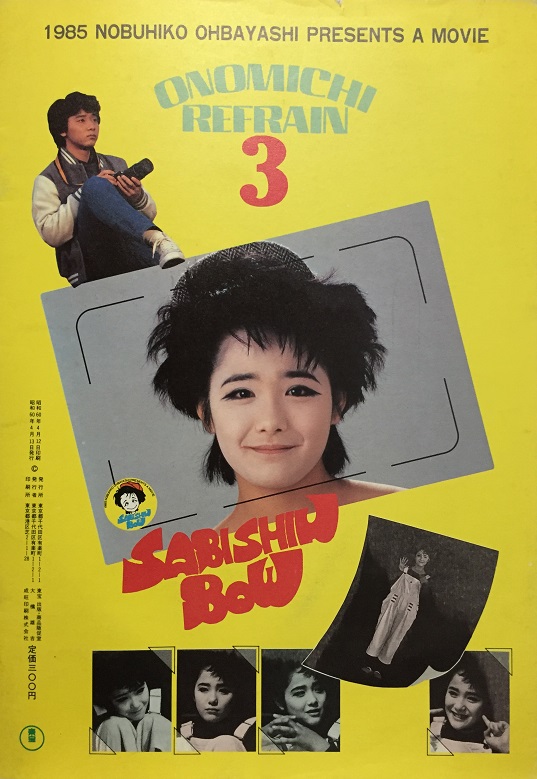

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process. Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long standing commitment to creating “populist” mainstream cinema but, perversely, he liked to spice it with a layer of arthouse inspired style. 2002’s Copycat Killer(模倣犯, Mohouhan) finds him back in the realm of literary adaptations with a crime thriller inspired by Miyuki Miyabe’s book in which the media becomes an accessory in the crazed culprit’s elaborate bid for eternal fame through fear driven notoriety.

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long standing commitment to creating “populist” mainstream cinema but, perversely, he liked to spice it with a layer of arthouse inspired style. 2002’s Copycat Killer(模倣犯, Mohouhan) finds him back in the realm of literary adaptations with a crime thriller inspired by Miyuki Miyabe’s book in which the media becomes an accessory in the crazed culprit’s elaborate bid for eternal fame through fear driven notoriety.