Japanese cinema of the 1980s is marked by an increasing desire to interrogate the idea of “the family” in an atmosphere of individualist consumerism. Yoshimitsu’s Morita’s The Family Game had blown the traditional ideas of filial piety and the primacy of the patriarch wide open in exposing his ordinary middle-class family as little more than a simulacrum as its various members sleepwalked through life playing the roles expected of them free of the true feeling one would expect to define familial bonds. A year later, Sogo Ishii’s The Crazy Family took a different, perhaps more positive approach, in depicting a family descending into madness through the various social pressures of maintaining a conventional middle-class life in the cramped environment of frenetic Tokyo. Masaki Kobayashi, unlike many of his contemporaries, was not so much interested in families as in individuals whose struggles to assert themselves in a conformist society became his major focus. The Empty Table (食卓のない家, Shokutaku no nai Ie) is not perhaps “a family drama” but it is, if indirectly, a drama about family and the ways in which the wider familial context of society at large often seeks to misuse it.

Japanese cinema of the 1980s is marked by an increasing desire to interrogate the idea of “the family” in an atmosphere of individualist consumerism. Yoshimitsu’s Morita’s The Family Game had blown the traditional ideas of filial piety and the primacy of the patriarch wide open in exposing his ordinary middle-class family as little more than a simulacrum as its various members sleepwalked through life playing the roles expected of them free of the true feeling one would expect to define familial bonds. A year later, Sogo Ishii’s The Crazy Family took a different, perhaps more positive approach, in depicting a family descending into madness through the various social pressures of maintaining a conventional middle-class life in the cramped environment of frenetic Tokyo. Masaki Kobayashi, unlike many of his contemporaries, was not so much interested in families as in individuals whose struggles to assert themselves in a conformist society became his major focus. The Empty Table (食卓のない家, Shokutaku no nai Ie) is not perhaps “a family drama” but it is, if indirectly, a drama about family and the ways in which the wider familial context of society at large often seeks to misuse it.

Set in 1973, The Empty Table is also among the earliest films to tackle the aftermath of the 1972 Asama-Sanso Incident. For ten days in February, the nation watched live as the police found themselves in a stand off with five United Red Army former student radicals who had taken the wife of an innkeeper hostage and holed up in a mountain lodge, refusing to give themselves up to the police. The discoveries surrounding the conduct of the United Red Army which had descended into a cult-like madness involving several murders of its members (including one of a heavily pregnant woman) shocked the nation and finally ended the student movement in Japan.

Kidoji (Tatsuya Nakadai) is the father of one of the student radicals, Otohiko (Kiichi Nakai), who took part in the siege. In Japanese culture, it’s usual for the parents of a person involved in a scandal to come forward and offer an official apology to the nation on behalf of the their children. During the siege itself the family had also been weaponised as mothers, particularly, were enlisted to shout from outside the inn, offering poignant messages intended to get their sons to give themselves up and come home. Kidoji, unlike the other fathers (one of whom hanged himself in shame), refuses his social obligation on the grounds that the actions of his grownup son are no longer his responsibility.

As a scientist, Kidoji is used to thinking things through in rational terms and outside of Japan his logic may seem unassailable – after all, it is unreasonable to hold the conduct of a family member against an otherwise upright and obedient citizen. In Japan however his actions make him seem cold and unfeeling, as if he has disowned both his son and his position as the father of a family with whom rests ultimate responsibility for those listed on his family register. This way of thinking may be very feudal, but it is the way things work not just in the late 20th century, but even in the early 21st.

Kidoji’s refusal to do what is expected of him eventually leads to the crumbling of the family unit. Far from the cheerful scene we see of Kidoji, his wife, and their three children seated around a dinner table in celebration, the family now eat separately and Kidoji returns home to cold meals and an empty table. Kidoji’s wife, Yumiko (Mayumi Ogawa), has had a breakdown and had to be hospitalised, while his daughter Tamae (Kie Nakai) is forced to break off her engagement only to resort to underhanded methods to be allowed to marry the man she loves. While Otohiko languishes in prison, only his younger brother Osamu (Takayuki Takemoto) remains at home.

Kobayashi’s central concern is the conflict in Kidoji’s heart as he faces a choice between maintaining his principles and saving his family pain. It’s not that Kidoji feels nothing – on the contrary, he is profoundly wounded by all that has happened to him, but ironically enough, puts on the face society expects but does not want in maintaining his composure in a situation of extreme difficulty. Kidoji’s deepest anxieties rest in the need to “take responsibility”, something he must do in acknowledging that it’s not his son’s disgrace which has destroyed his family but his own rigidity in refusing to bend his principles and obey social convention. What Kidoji wants is for his son to take responsibility for his own choices as an individual rather than expecting his family to carry his load for him. He must, however, also take responsibility for the effect his choices have had on others, including on his family, and accept his role both as an individual and as a member of a society with rights and obligations.

Kidoji’s refusal to apologise on behalf of his son looks to the rest of society like an abnegation of his paternal authority, and without paternal authority the family unit crumbles like a feudal household whose lord has been murdered. Yet Kidoji, like many of Kobayashi’s heroes, refuses to compromise his principals no matter how much personal pain they eventually cause him. Where the rules of society make no sense to him, he will ignore (if not quite oppose) them, remaining true to his own notions of moral righteousness.

In many ways, Kidoji is the archetypal Kobayashi hero – standing up to social oppression and refusing to simply give in even when he knows how beneficial that may be to all concerned. He is also, however, just as problematic in allowing his family to continue suffering in preservation of his personal beliefs. Kobayashi’s final feature film, The Empty Table is extremely dated in terms of shooting style with its overly theatrical dialogue and frequent use of voice over and monologue which were long out of fashion by the mid-1980s. Kobayashi does, however, return to the more expressionist style of his earlier career, moving towards an etherial sense of poetry as his hero contemplates his place in a society which often asks him to behave in ways which compromise his essential value system. The family, broken as it is, is also (partly) mended once again as Kidoji begins to reconcile his various “responsibilities” into a more comprehensive whole as he prepares to welcome a new generation seemingly as determined to live in as principled and unorthodox a way as he himself has.

Shiro Toyoda, despite being among the most successful directors of Japan’s golden age, is also among the most neglected when it comes to overseas exposure. Best known for literary adaptations, Toyoda’s laid back lensing and elegant restraint have perhaps attracted less attention than some of his flashier contemporaries but he was often at his best in allowing his material to take centre stage. Though his trademark style might not necessarily lend itself well to horror, Toyoda had made other successful forays into the genre before being tasked with directing yet another take on the classic ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談) but, hampered by poor production values and an overly simplistic script, Toyoda never succeeds in capturing the deep-seated dread which defines the tale of maddening ambition followed by ruinous guilt.

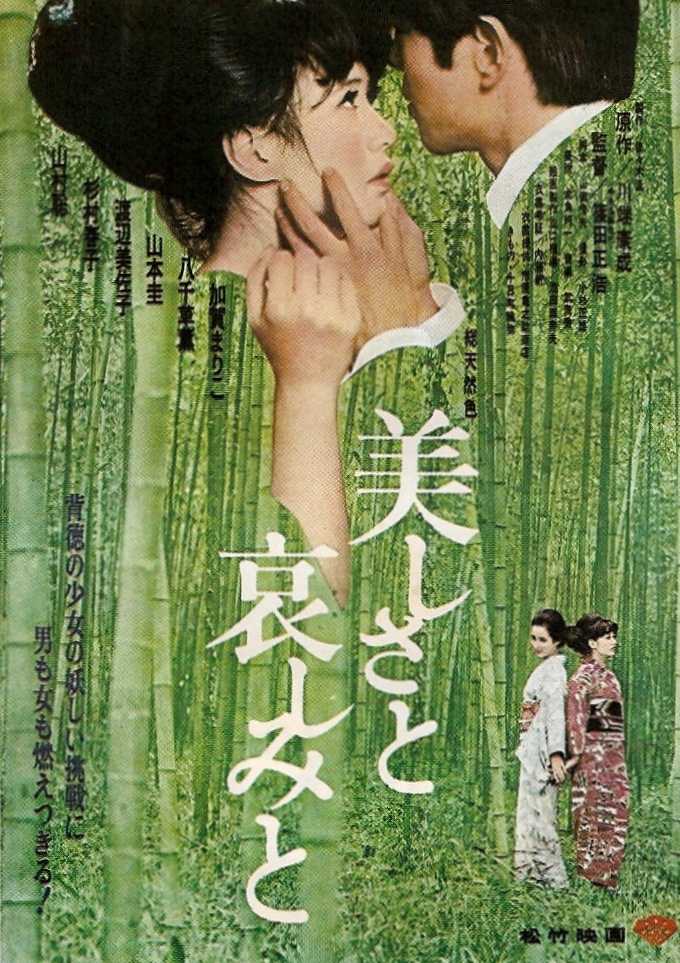

Shiro Toyoda, despite being among the most successful directors of Japan’s golden age, is also among the most neglected when it comes to overseas exposure. Best known for literary adaptations, Toyoda’s laid back lensing and elegant restraint have perhaps attracted less attention than some of his flashier contemporaries but he was often at his best in allowing his material to take centre stage. Though his trademark style might not necessarily lend itself well to horror, Toyoda had made other successful forays into the genre before being tasked with directing yet another take on the classic ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談) but, hampered by poor production values and an overly simplistic script, Toyoda never succeeds in capturing the deep-seated dread which defines the tale of maddening ambition followed by ruinous guilt. Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession.

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession. Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus,

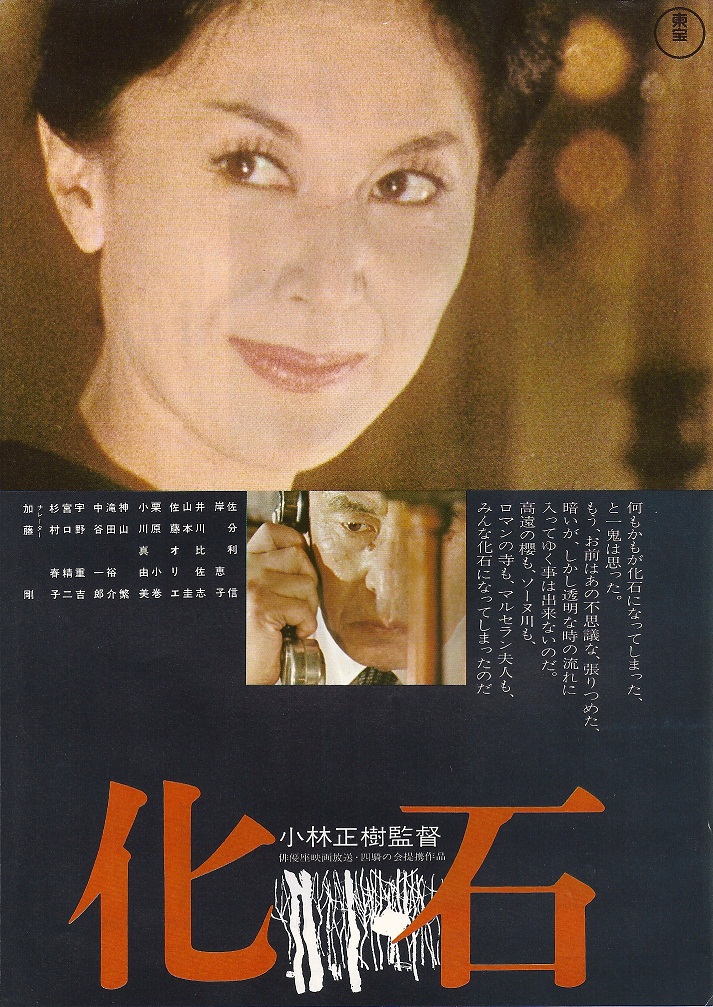

Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus,  “Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period.

“Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period. Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon.

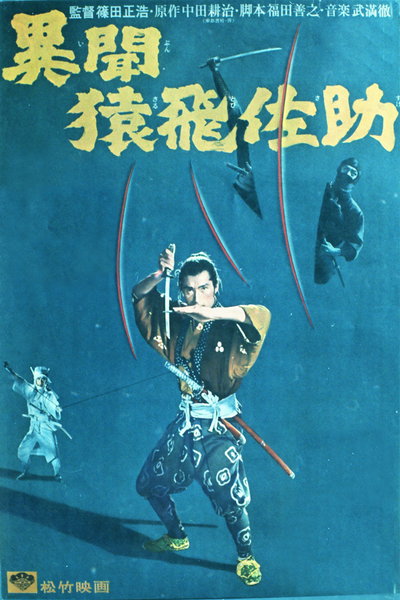

Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon. Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?