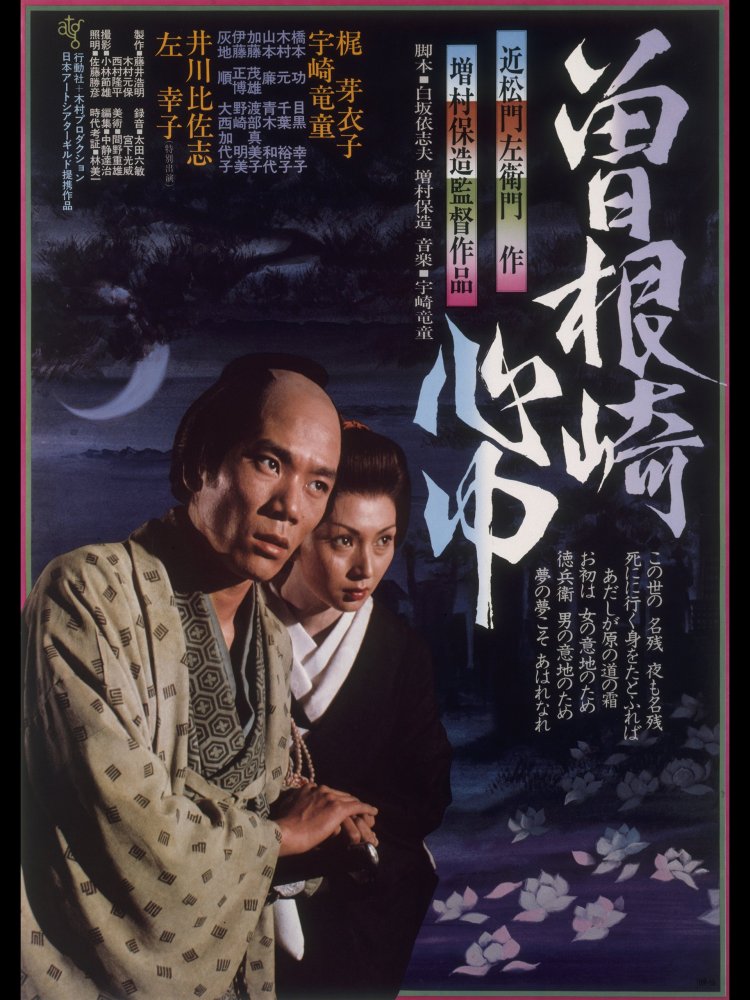

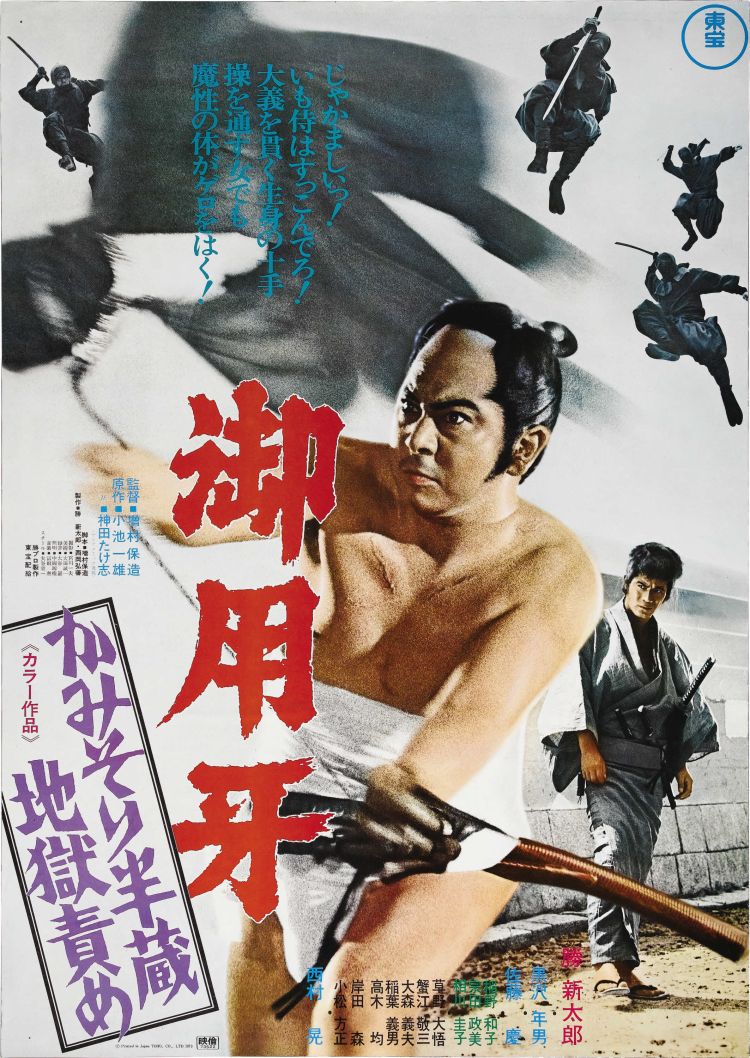

After spending the vast majority of his career at Daiei, Yasuzo Masumura found himself at something of a loose end when the studio went bankrupt in the early ‘70s. Working as a freelance director for hire he made the best of what was available to him, even contributing an instalment in former Daiei star Shinataro Katsu’s series of period exploitation films, Hanzo the Razor: The Snare. There is, however, a particular shift in the famously fearless director’s point of view in these later films as his erotically charged grotesquery begins to soften into something more like an aching sadness in the crushing sense of defeat and impossibility which seems to consume each of his heroes. Maintaining the contemporary groove of Lullaby of the Earth – an uncharacteristically new age inflected tale of a naive orphan from the mountains tricked into the sex trade through a desire to see the sea, Double Suicide at Sonezaki (曽根崎心中, Sonezaki Shinju, AKA Love Suicides at Sonezaki / Double Suicides of Sonezaki, Double Suicide in Sonezaki) is a melancholy exploration of the limitations of love as a path to freedom in which the demands of a conformist, hierarchical society erode the will of those who refuse to compromise their personal integrity on its behalf until they finally accept that there is no way in which they can possibility continue to live inside it.

After spending the vast majority of his career at Daiei, Yasuzo Masumura found himself at something of a loose end when the studio went bankrupt in the early ‘70s. Working as a freelance director for hire he made the best of what was available to him, even contributing an instalment in former Daiei star Shinataro Katsu’s series of period exploitation films, Hanzo the Razor: The Snare. There is, however, a particular shift in the famously fearless director’s point of view in these later films as his erotically charged grotesquery begins to soften into something more like an aching sadness in the crushing sense of defeat and impossibility which seems to consume each of his heroes. Maintaining the contemporary groove of Lullaby of the Earth – an uncharacteristically new age inflected tale of a naive orphan from the mountains tricked into the sex trade through a desire to see the sea, Double Suicide at Sonezaki (曽根崎心中, Sonezaki Shinju, AKA Love Suicides at Sonezaki / Double Suicides of Sonezaki, Double Suicide in Sonezaki) is a melancholy exploration of the limitations of love as a path to freedom in which the demands of a conformist, hierarchical society erode the will of those who refuse to compromise their personal integrity on its behalf until they finally accept that there is no way in which they can possibility continue to live inside it.

Ohatsu (Meiko Kaji), the geisha, has fallen in love with a client – Tokubei (Ryudo Uzaki), who is a humble man taken in by an uncle with the intention that he take over his soy-sauce shop. No longer the relationship between a prostitute and a customer, Ohatsu refuses to take Tokubei’s money which begins to cause friction with her “master” at the brothel to whom she still owes a significant debt. Tokubei does not possess the resources to redeem her, nor is he ever likely to. Matters are forced to a crisis point when each of them is offered what would usually be thought the best possible option for their respected social paths. Tokubei is offered the hand in marriage of his aunt’s niece and the chance to set up his own shop in Edo but it isn’t what he wants because he wants Ohatsu. Similarly, Ohatsu is sought by a wealthy client who wants to buy her and take her home as a mistress – she tries to refuse but has to play along given her relative lack of agency, longing to be with Tokubei or no one at all. Tokubei is thrown out by his uncle for refusing the marriage and finds himself the difficult position of having to reclaim dowry money from his greedy step-mother only to be conned out of it by an unscrupulous “friend”, Kuheiji (Isao Hashimoto), who later frames him to make it look like Tokubei cheated him. Beaten and ostracised, Tokubei sees no escape from his shame other than through an “honourable” death and Ohatsu sees no life for herself without her love.

Inspired by Chikamatsu’s world of double suicides, Masumura adopts a deliberately theatrical method of expression in which the cast perform in a heightened and rhythmic style intended to evoke the classical stage of Japan. Yet he also makes a point of scoring the film with contemporary folk and jazz as if this wasn’t such an old story after all. Times may be more permissive, but perhaps there’s no more freedom in love than there ever was and the pure dream of happiness in romantic fulfilment no more possible.

The forces that keep Tokubei and Ohatsu apart are only partly those unique to the feudal world – debt bondages and filial obligations being much weakened if not altogether absent in the post-war society, but are almost entirely due to their lack of individual agency and impossibility of freeing themselves from the various systems which oppress them. Tokubei is a poor boy from the country whose father has died. He has been taken in by an uncle and trained up as an heir – something he is grateful for and has worked hard to repay, but will not sacrifice his individual desire in order to accept the path laid down for him.

Ohatsu, in a more difficult position, is oppressed not only by her poverty but by her gender. Sold to a brothel she is subject to debt bondage and viewed only as a commodity, never as a person. When she intervenes to stop Tokubei being beaten by Kuheiji’s thugs, her patron panics but only because he will lose his money if she is “damaged”. Similarly, the brothel owner complains for the same reason after some ruckus at the inn. Neither of them are very much bothered about Ohatsu in herself but solely in her functionality as tool for making money or making merry respectively.

“Money is better, money means everything” claims Tokubei’s angry step-mother and she certainly seems to have a point as both of our lovers struggle through their lack of it. In the end it’s not so much money but “shame” which condemns them to a sad and lonely death as they realise they can no longer live with themselves in this cruel and unforgiving world which refuses them all hope or possibility for the future. An honourable man, Tokubei cannot live with such slander – men die for honour, and women for love, as Ohatsu puts it. Ironically enough there was a chance for them but it came too late as Kuheiji’s machinations begin to blow back on him and Tokubei’s uncle begins to regret his overhasty disowning of his nephew, but the world is still too impure for such pure souls and so they cannot stay.

Unlike some of Masumura’s earlier work, there’s a sadness and an innocence implicit in Double Suicide at Sonezaki that leaves defiance to one side only to pick it up again as the lovers decry their love too pure to survive in an impure world. The world does not deserve their love, and so they decide to leave it, freeing themselves from the “shame” of living through the purifying ritual of death. Softer and sadder, the message is not so far from the director’s earlier assertions save for being bleaker, leaving no space for love in an oppressive and conformist society which demands a negation of the soul as the price for acceptance into its world of cold austerity.

Opening (no subtitles)

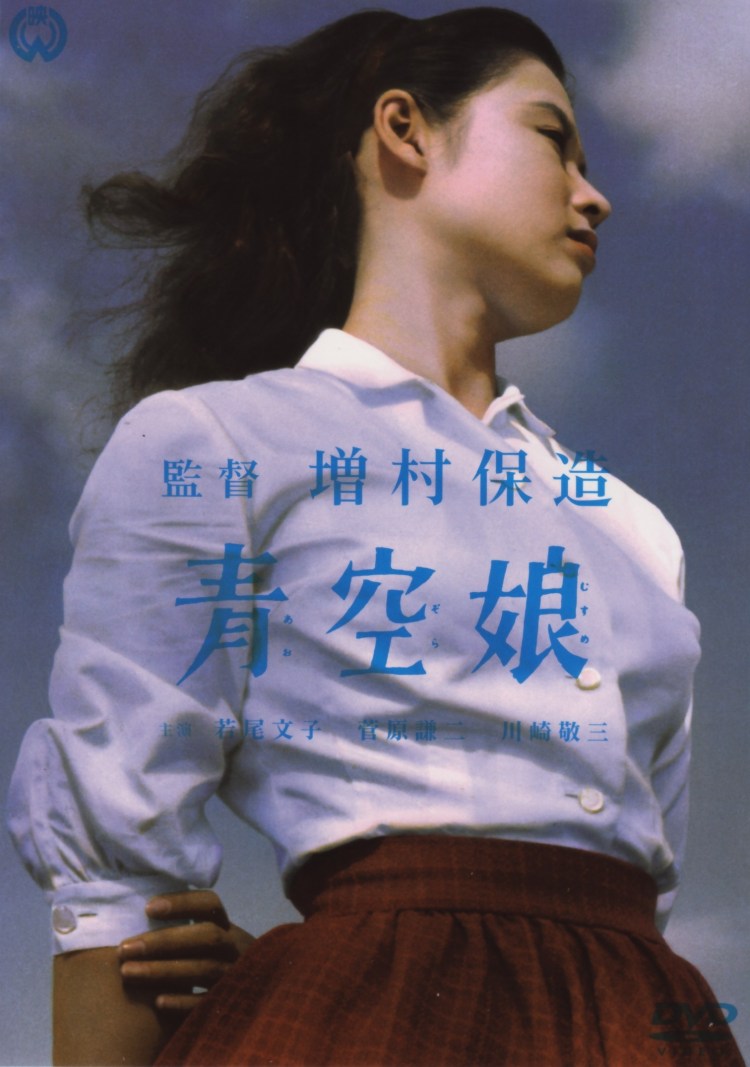

If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story

If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story

For arguably his most famous film, 1964’s Manji (卍), Masumura returns to the themes of destructive sexual obsession which recur throughout his career but this time from the slightly more unusual angle of a same sex “romance”. However, this is less a tale of lesbian true love frustrated by social mores than it is a critique of all romantic entanglements which are shown to be intensely selfish and easily manipulated. Based on Tanizaki’s 1930s novel Quicksand, Manji is the tale of four would be lovers who each vie to be sun in this complicated, desire filled galaxy.

For arguably his most famous film, 1964’s Manji (卍), Masumura returns to the themes of destructive sexual obsession which recur throughout his career but this time from the slightly more unusual angle of a same sex “romance”. However, this is less a tale of lesbian true love frustrated by social mores than it is a critique of all romantic entanglements which are shown to be intensely selfish and easily manipulated. Based on Tanizaki’s 1930s novel Quicksand, Manji is the tale of four would be lovers who each vie to be sun in this complicated, desire filled galaxy. Never one to take his foot off the accelerator, Yazuso Masumura hurtles headlong into the realms of surreal horror with 1969’s Blind Beast (盲獣, Moju). Based on a 1930s serialised novel by Japan’s master of eerie horror, Edogawa Rampo, the film has much more in common with the wilfully overwrought, post gothic European arthouse “horror” movies of period than with the Japanese. Dark, surreal and disturbing, Blind Beast is ultimately much more than the sum of its parts.

Never one to take his foot off the accelerator, Yazuso Masumura hurtles headlong into the realms of surreal horror with 1969’s Blind Beast (盲獣, Moju). Based on a 1930s serialised novel by Japan’s master of eerie horror, Edogawa Rampo, the film has much more in common with the wilfully overwrought, post gothic European arthouse “horror” movies of period than with the Japanese. Dark, surreal and disturbing, Blind Beast is ultimately much more than the sum of its parts. Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama

Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama  The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes.

The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes.