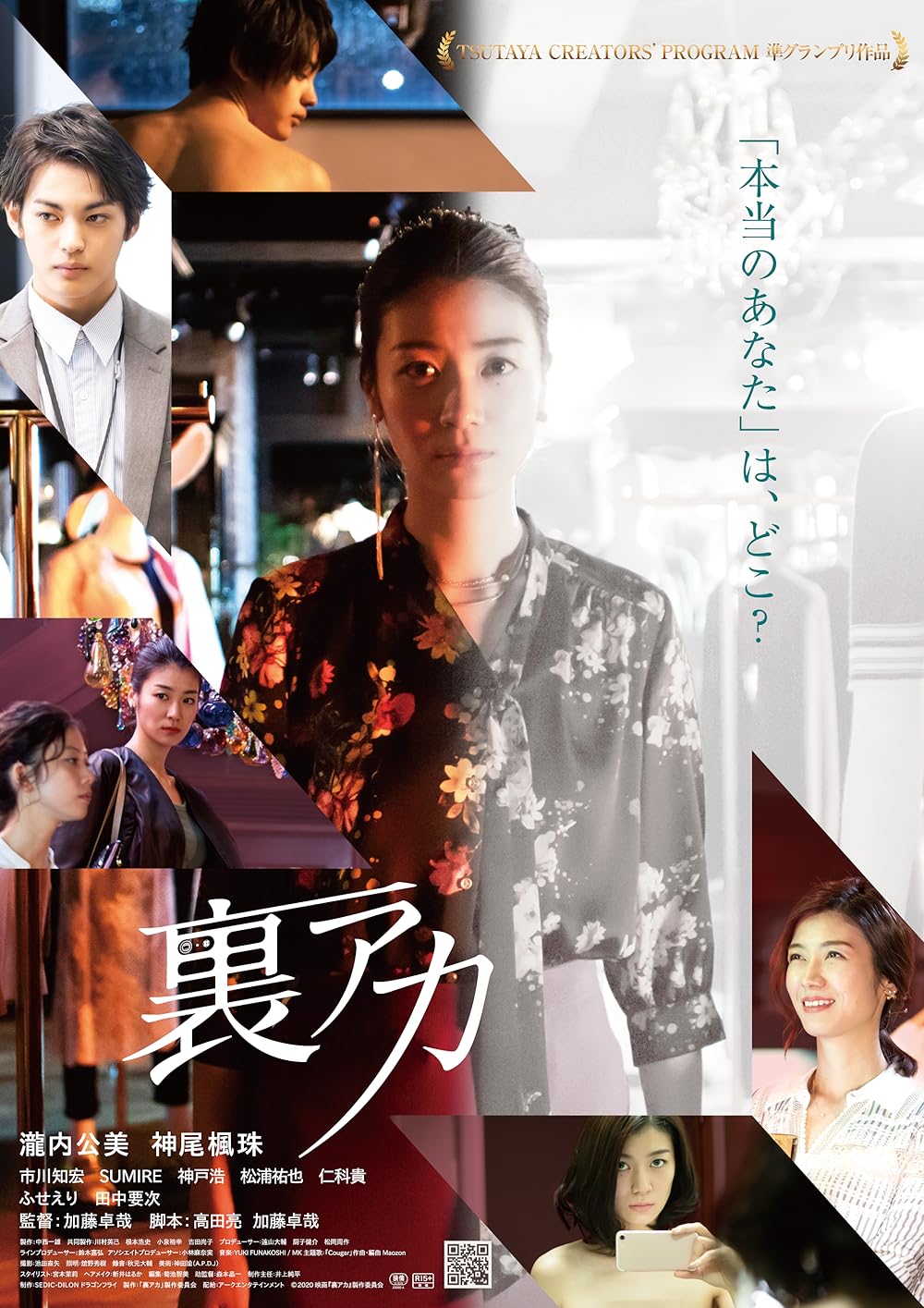

Frustrated by career setbacks and loneliness in her personal life, 34-year-old boutique store manager Machiko (Kumi Takiuchi) decides to open a secret Twitter account to rival a younger colleague’s Instagram success. To boost her follower count, she starts posting photos of her breasts which become increasingly explicit as if she were stripping herself bare as pathway towards liberation. When a random man contacts her, she eventually agrees to meet and has a torrid night of steamy sex she had not intended as a one night stand though her much younger date, Yuto (Fuju Kamio), had other ideas.

In her voiceover, Machiko recounts that there was a kind of excitement she felt on her first night in Tokyo that she evidently no longer feels. We see her pick out clothing from a dumpster we later infer to be from stock she bought as a buyer for the store that didn’t sell and intuit that it stands in for Machiko herself who also feels as if she’s been thrown away and abandoned by her workplace. After making a loss on the clothes, they demoted her to manager and now ignore her warnings that the new designs they’re going for are too safe. Her colleague agrees with her and calls them boring but soon changes her tune when the new buyer shows up, telling him she thinks they’re great and wants to buy some herself.

Walking through the store in a daze, Machiko becomes increasingly obsessed with her secret account and is dependent on the sense of validation she gets from skeevy men liking her posts and expressing a desire to sleep with her. She later confesses that she started the account out of a sense of loneliness and a desire to be wanted, but also because she realised that her life was empty and she had nothing at all to show for her work. Though she’d devoted herself to her career, she’s not been rewarded and her bosses are sidelining her because of her age and gender while she’s forgone personal relationships and is perhaps romantically naive and lonely.

Sex with random men which they video and she posts on her channel provokes a kind of liberation but also deepens her sense of loneliness. Yuto, the man she met who originally reignited a spark she thought had gone out, makes a habit of approaching women on social media and having sex with them which he videos as a kind of trophy. When he crassly shows her the tapes believing her to be a kind of ally after an unexpected reunion, she remarks that all the women are her as if seeing herself for the first time. Yuto, meanwhile, suggests that he did out of a sense of nihilism that his life had been too easy and its lack of imperfection was too difficult to bear.

The new clothing line Machiko suggests to save the failing store is ironically to be called “The Real You,” though that’s something she’s perhaps lost sight of after splitting her persona in two with the secret account making it impossible to see who the “real” Machiko might be. Nevertheless, newfound confidence does seem to improve her working life even as she’s sucked into the potential danger of Yuto’s nihilistic existence. He takes her to a working-class eatery, spinning a tale of small town upbringings and factory closures that may or may not be true but in any case expresses his own loneliness in his potentially self-destructive tale of big city success.

Yuto’s motto, which turns out to be not entirely his own, is to have fun in world which isn’t bearing out his dissatisfaction with the contemporary society even if it turns out his issue is ennui rather than a genuine reaction to the kind of issues that colour Machiko’s existence like ageism, sexism, and the vagaries of the fashion industry. Seemingly informed by Roman Porno, Kato shoots the city with moody melancholy but finally allows Machiko to begin reintegrating herself though throwing away her phone and everything that comes with it. Detaching from the urban environment, she begins to run as if reclaiming her physicality and desire for forward motion before finally arriving at the dawn suggesting that her long night of the soul is finally over and a new life awaits.

Ura Aka: L’Aventure screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (no subtitles)

Images: © 2020 Ura-Aka L’Aventure Production Committee