Back in the 1980s, you could make a film that’s actually no good at all but because of its fluffy, non-sensical cheesiness still manages to salvage something and capture the viewer’s good will in the process. In the intervening thirty years, this is a skill that seems to have been lost but at least we have films like Taylor Wong’s Behind the Yellow Line (緣份, Yuan Fen) to remind us this kind of disposable mainstream youth comedy was once possible. Starring three youngsters who would go on to become some of Hong Kong’s biggest stars over the next two decades, Behind the Yellow Line is no lost classic but is an enjoyable time capsule of its mid-80s setting.

Back in the 1980s, you could make a film that’s actually no good at all but because of its fluffy, non-sensical cheesiness still manages to salvage something and capture the viewer’s good will in the process. In the intervening thirty years, this is a skill that seems to have been lost but at least we have films like Taylor Wong’s Behind the Yellow Line (緣份, Yuan Fen) to remind us this kind of disposable mainstream youth comedy was once possible. Starring three youngsters who would go on to become some of Hong Kong’s biggest stars over the next two decades, Behind the Yellow Line is no lost classic but is an enjoyable time capsule of its mid-80s setting.

Paul (Leslie Cheung) is a mild mannered guy trying to get to work on time and make a good impression on his first day on the job but after having a taxi stolen out from under him and having to run some of the way, he rushes onto the underground where he has a meet cute with Monica (Maggie Cheung) – a sad looking lady who barely notices his presence. Paul is smitten and follows her onto the train where she continues to ignore him. Despite his best efforts he makes more of an impression on Anita (Anita Mui) – a wealthy and extremely fashionably dressed woman with giant 80s hair! Anita makes a play for Paul but he only has eyes for Monica. Monica is just getting over a failed affair with a married man and isn’t really sure of anything anymore. It’s all in the hands of fate and the mass transit authority but will true love really run its course?

Behind the Yellow Line (presumably so named for its train station setting, the chinese title is simply “fate”) is meandering mess of a picture though very much typical of its time. Paul and Monica get together but she’s still torn over her married lover who resurfaces at the most inconvenient moment whilst also fighting off the attentions of her flirtatious boss causing Paul to overreact in fit of jealously and almost ruin everything in the process. Eventually they decide to sort things out with a game of fate as Monica hides on the MTR expecting Paul to successfully pin point her location before the last train rolls so that she knows they are truly destined to be together.

This central spine of the film works well enough as Paul and Monica tempt fate with their true love romance but where does Anita fit into all this? Popping up now and then almost at random, Anita seems like a strange after thought or a refugee from another film. A stock ‘80s style kooky character, she’s all big hair and bold makeup but she’s also a wealthy woman trying to buy Paul (or more particularly his parents) with the promise of material security. ‘80s setting aside, consumerism is only a mild bi-product and neither Paul nor Monica is particularly pressed over material concerns – all that matters here is true love destiny and the successful resolution of their romantic difficulties. Anita becomes a kind of cupid, forsaking her own feelings in order to satisfy Paul’s in gesture of true love that also recognises having lost out in the great game of fate as her feelings are not returned. Or, there are things money cannot fix (at least, not in the way you want it to).

In this way Behind the Yellow line becomes more interesting as it’s Anita and Monica who begin to move the plot. Monica is quick to remind us that she’s a single woman and she has the right to choose – in this case, she feels sorry for both of her potential partners (whilst completely disinterested in her boss) and so is inclined to decide to remain alone. The film obviously doesn’t go this way, but it does present her choice as a perfectly valid one whilst also affording her the agency to choose her own destiny right the way through. Anita largely wields her power through her money (which appears to be inherited, the gang of other young people she hangs round with seem to be wealthy too making her choice of Paul a relatively strange one), but she exercises her individuality through her unconventional behaviour and bold fashion choices, refusing to give in to social norms but submitting to “destiny” in acknowledging that her feelings are unrequited.

Very much of its time, Behind the Yellow Line is an obvious piece of disposable entertainment designed to appeal to a very specific audience. Filled with cheerful ‘80s cantopop and bright neon lighting there’s relatively little angst in this tale of youthful romance. Everything bounces along much as one would expect with no melodramatic intrusions save Monica’s sometimes melancholy indecisiveness and Paul’s diffidence. Structurally the film is riddled with problems not least with its use of Anita who seems to appear and disappear as needed with no clear indication of her precise function yet it provides enough silly humour and good natured drama to coast though without too many problems. No great lost classic but enjoyable enough, Behind the Yellow is worth seeking out if only to witness the genesis of these three soon to be giants of the entertainment world whose careers became curiously intertwined before ending much too soon in the early years of the following century.

2003 Celestial Pictures trailer (English subtitles)

Original 1984 Cantonese trailer (English subtitles for onscreen text only, no subtitles for dialogue)

Johnnie To is best known as a purveyor of intricately plotted gangster thrillers in which tough guys outsmart and then later outshoot each other. However, To is a veritable Jack of all trades when it comes to genre and has tackled just about everything from action packed crime stories to frothy romantic comedies and even a musical. This time he’s back in world of the medical drama as an improbable farce develops driven by the three central cogs who precede to drive this particular crazy train all the way to its final destination.

Johnnie To is best known as a purveyor of intricately plotted gangster thrillers in which tough guys outsmart and then later outshoot each other. However, To is a veritable Jack of all trades when it comes to genre and has tackled just about everything from action packed crime stories to frothy romantic comedies and even a musical. This time he’s back in world of the medical drama as an improbable farce develops driven by the three central cogs who precede to drive this particular crazy train all the way to its final destination. It’s become almost a cliché to describe a sequel as “unnecessary”, but then assessing how any sequel or, indeed, any film might be deemed “necessary” (for what or whom?) proves more fraught than one might originally think. It might, then, be better to think of certain sequels as “unwise” – S Storm (S風暴), a followup to the similarly named Z Storm is just one such film. Z Storm’s critical reception was, shall we say, lukewarm and did not exactly inspire a burning desire to return to its world of corporate corruption vs different kinds of bickering policemen but, nevertheless, here we are.

It’s become almost a cliché to describe a sequel as “unnecessary”, but then assessing how any sequel or, indeed, any film might be deemed “necessary” (for what or whom?) proves more fraught than one might originally think. It might, then, be better to think of certain sequels as “unwise” – S Storm (S風暴), a followup to the similarly named Z Storm is just one such film. Z Storm’s critical reception was, shall we say, lukewarm and did not exactly inspire a burning desire to return to its world of corporate corruption vs different kinds of bickering policemen but, nevertheless, here we are.

Cold War 2 (寒戰II) arrives a whole four years after the original

Cold War 2 (寒戰II) arrives a whole four years after the original

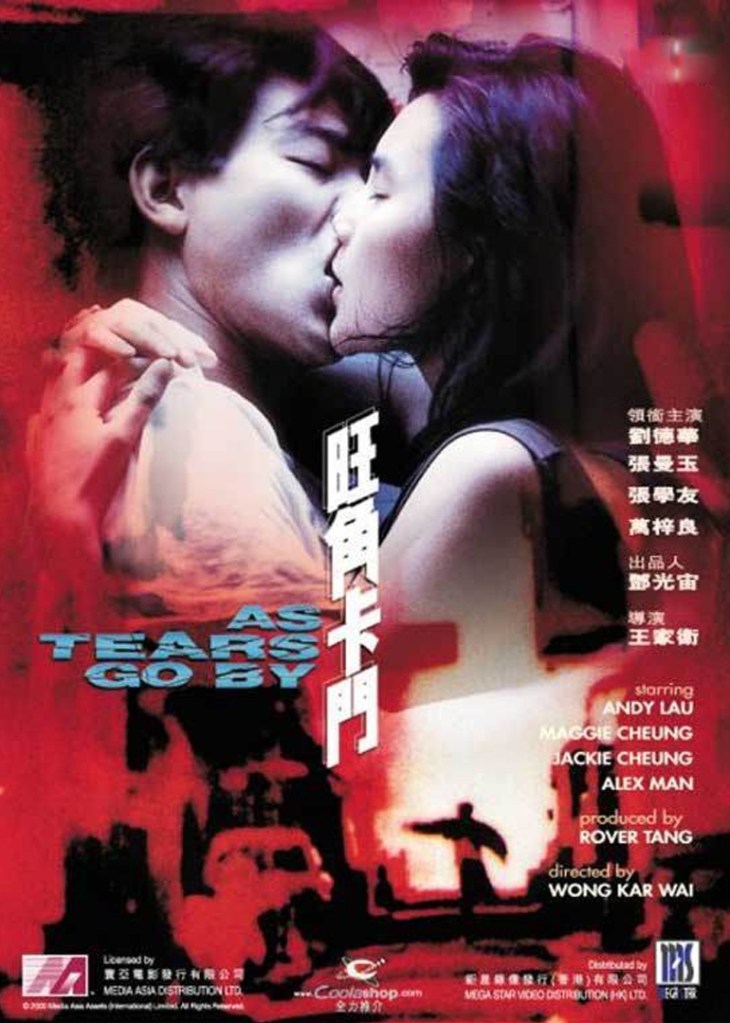

These days, Wong Kar-wai is an international auteur famous for his stories of lovelorn heroes trapped inside their memories, endlessly yearning in vain for the unattainable. In many ways his debut feature, As Tears Go By (旺角卡門, Mongkok Carmen) is little different save that it owes more to its vague heroic bloodshed, gangster inspiration and is less about memory than inevitability and a man abandoning his dreams of a better life with a woman he loves out of mistaken loyalty to his loose cannon friend.

These days, Wong Kar-wai is an international auteur famous for his stories of lovelorn heroes trapped inside their memories, endlessly yearning in vain for the unattainable. In many ways his debut feature, As Tears Go By (旺角卡門, Mongkok Carmen) is little different save that it owes more to its vague heroic bloodshed, gangster inspiration and is less about memory than inevitability and a man abandoning his dreams of a better life with a woman he loves out of mistaken loyalty to his loose cannon friend. Where oh where are the put upon citizens of martial arts movies supposed to grab a quiet cup of tea and some dim sum? Definitely not at Boss Cheng’s teahouse as all hell is about to break loose in there when it becomes the centre of a turf war in gloomy director Kuei Chih-Hung’s social minded modern day kung-fu movie The Teahouse (成記茶樓, Cheng Ji Cha Lou).

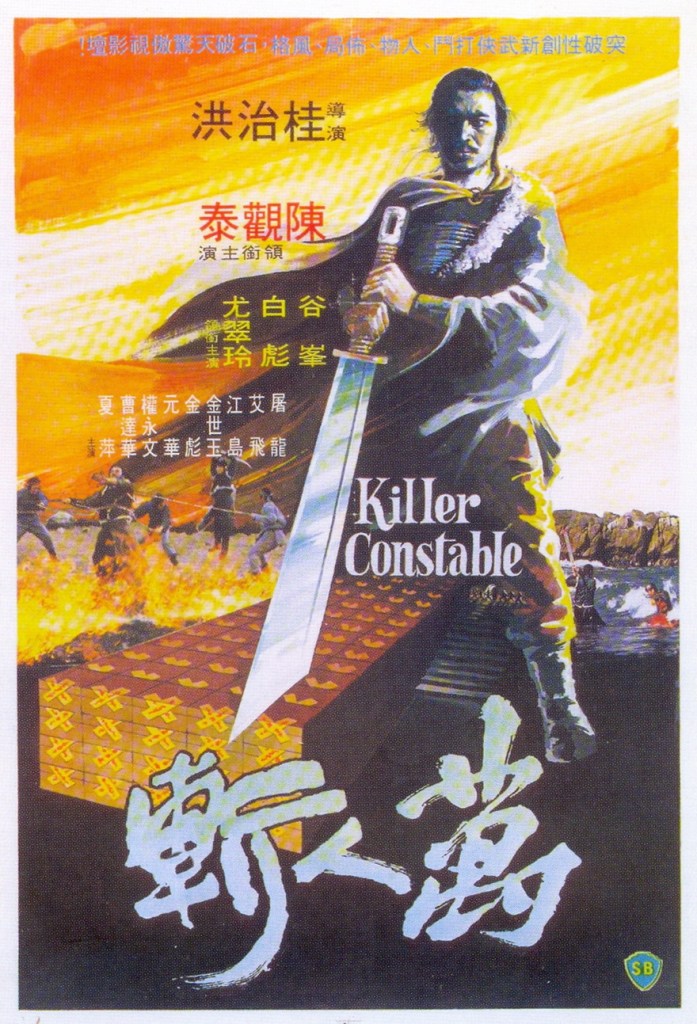

Where oh where are the put upon citizens of martial arts movies supposed to grab a quiet cup of tea and some dim sum? Definitely not at Boss Cheng’s teahouse as all hell is about to break loose in there when it becomes the centre of a turf war in gloomy director Kuei Chih-Hung’s social minded modern day kung-fu movie The Teahouse (成記茶樓, Cheng Ji Cha Lou). Every sovereign needs that one ultra reliable and supremely talented servant who can be called upon in desperate times. For the Dowager Empress of the Qing Empire, that man is Leng Tien-Ying – otherwise known as the Killer Constable. When a sizeable amount of gold goes missing from the Imperial Vaults, it’s Leng they call to try and get it back. However, what Leng doesn’t know is that there’s far more going on here than he could possibly have imagined and he’s about to wade into a trap so deep that you never even see the bottom.

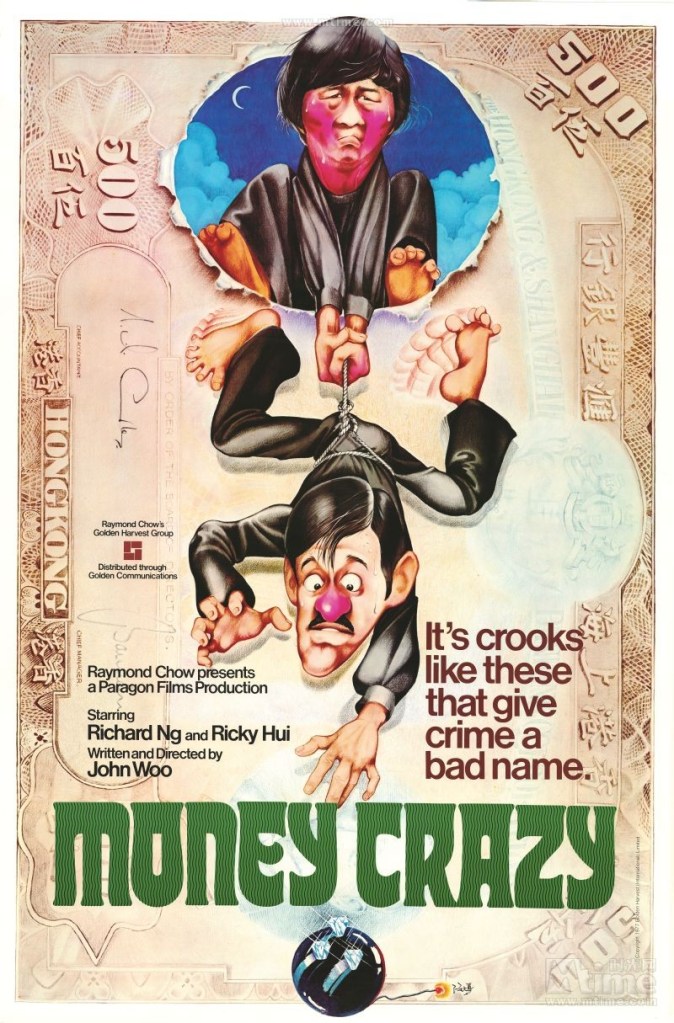

Every sovereign needs that one ultra reliable and supremely talented servant who can be called upon in desperate times. For the Dowager Empress of the Qing Empire, that man is Leng Tien-Ying – otherwise known as the Killer Constable. When a sizeable amount of gold goes missing from the Imperial Vaults, it’s Leng they call to try and get it back. However, what Leng doesn’t know is that there’s far more going on here than he could possibly have imagined and he’s about to wade into a trap so deep that you never even see the bottom. John Woo is best known in the West for his “heroic bloodshed” movies from the ‘80s in which melancholy tough guys shoot bullets at each other in beautiful ways. However, he had a long and varied career even before which began with Shaw Brothers and a stint in traditional martial arts movies. What often gets over looked outside of Woo’s native Hong Kong is his many comedies, of which The Pilferer’s Progress (AKA Money Crazy, 发钱寒, Fa Qian Han) is one of his most successful.

John Woo is best known in the West for his “heroic bloodshed” movies from the ‘80s in which melancholy tough guys shoot bullets at each other in beautiful ways. However, he had a long and varied career even before which began with Shaw Brothers and a stint in traditional martial arts movies. What often gets over looked outside of Woo’s native Hong Kong is his many comedies, of which The Pilferer’s Progress (AKA Money Crazy, 发钱寒, Fa Qian Han) is one of his most successful.