In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support.

In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support.

Haruhiko (Joe Odagiri), Himiko’s much younger lover and the manager of the home, is determined to reunite his boss with his estranged daughter, Saori (Kou Shibasaki), before it’s too late. Saori is a rather sour faced and sullen woman carrying a decades long grudge against the father who abandoned her as a child and consigned her mother to a life of misery and heartbreak, so Haruhiko’s invitations are not warmly received. Haruhiko is not the giving up type and manages to sweet talk Saori’s colleague into revealing her desperate financial situation which has her already working two jobs with a part-time stint in a combini on top of her regular work during which she finds herself looking at lucrative ads for work on sex lines. When Haruhiko offers her a well paying gig helping out at the home, she has no choice but to put her pride aside.

The exclusively male residents of La Maison de Himiko lived their lives during a time when it was almost impossible to be openly gay. Consequently many of them have been married and had children but later left their families to live a more authentic life. Unfortunately, times being what they were, this often meant that they lost contact with their sons or daughters, even if they were able to keep in touch with their ex-wives or other family members for updates. For these reasons, La Maison de Himiko provides an invaluable refuge for older men who have nowhere else to go as they enter the later stages of their lives. The home provides not only a safe space where everybody is free to be themselves but also a sense of community and interdependence.

Though the situation is much improved, it is still imperfect as the home and its residents continue to face prejudice from the outside world. Saori, still carrying the pain of her father’s rejection, views his choice as a selfish one which placed his own desires above the duty he should have felt towards his wife and child. Partly driven by her resentment, Saori has a somewhat negative view of homosexuality on arriving at the home, offering up a selection of homophobic slurs, and is slow to warm to the residents. Gradually getting to know her father again and through her experiences at the home, her attitude slowly changes until she finds herself physically defending her new found friend when he’s set upon by a drunken former colleague who publicly shames him in a nightclub.

The home is also plagued by a gang of bratty kids who often leave homophobic graffiti scrawled across the front wall. One of their early tricks involves throwing a bunch of firecrackers under a parked car to stun Saori so they can hold her captive for a bit because they have really a lot of questions about lesbians and they wondered if she was one, though one wonders what they’d do if someone answered them seriously. Predictably, the leader of the bratty kids may be engaging in these kinds of behaviours because he’s confused himself. Thankfully La Maison de Himiko is an open and forgiving place, welcoming the boy inside to offer support to a young man still trying to figure himself out.

This is not a coming out story, but it is a plea for tolerance and acceptance through which Saori herself begins to blossom, easing her anger and resentment and sending her trademark scowl away with them. One of her closest friends at the home is a shy man who lived most of his life in the closet but makes the most beautiful embroidered clothes and elegant dresses. Sadly, the most lovely of them is reserved for his funeral – he’s too ashamed to wear it alive because he doesn’t like the way he looks in the mirror. Eventually he and Saori end up having an unconventional fancy dress party in which they both break out of their self imposed prisons culminating in a joyous group dance routine in a local nightclub.

Joe Odagiri turns in another nuanced, conflicted performance as the increasingly confused Haruhiko who finds himself oddly drawn to Saori’s sullen charms though the film thankfully avoids “turning” its male lead for an uncomfortable romantic conclusion. A young man among old ones, Haruhiko is somewhat out of place but has his own empty spaces. Revealing to Saori that he lives only for desire he betrays a nagging fear of his own emptiness and journey into a possibly lonely old age. Nevertheless, La Maison de Himiko is generally bright and cheerful despite some of the pain and sadness which also reside there. A warm and friendly tribute to the power of community, La Maison de Himiko is a hymn in praise of tolerance and inclusivity which, as it makes plain, bloom from the inside out.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

And the fantastic dance sequence from the film

Plus the original version of the song (Mata Au Hi Made) by Kiyohiko Ozaki

Do you know Hong Sang-soo? So asks the heroine of Miss Ex (비치온더비치, Bitch on the Beach) as part of her nefarious mission to win back her childhood sweetheart. Unfortunately, his reply is to ask if he directed The Host, so Ga-young (Jeong Ga-young) is out of luck with her Dark Knight loving former love, but possibly in luck with us as her movie obsessed ramblings and strange stories about accidental AIDS tests during wisdom tooth extractions continue to dominate the screen for the next 90 minutes. Divided into three chapters and filmed in an oddly colourful black and white, director and leading actress’ Jeong Ga-young’s debut feature channels Hong Sang-soo by way of Woody Allen and the French New Wave but may prove funnier than all three put together.

Do you know Hong Sang-soo? So asks the heroine of Miss Ex (비치온더비치, Bitch on the Beach) as part of her nefarious mission to win back her childhood sweetheart. Unfortunately, his reply is to ask if he directed The Host, so Ga-young (Jeong Ga-young) is out of luck with her Dark Knight loving former love, but possibly in luck with us as her movie obsessed ramblings and strange stories about accidental AIDS tests during wisdom tooth extractions continue to dominate the screen for the next 90 minutes. Divided into three chapters and filmed in an oddly colourful black and white, director and leading actress’ Jeong Ga-young’s debut feature channels Hong Sang-soo by way of Woody Allen and the French New Wave but may prove funnier than all three put together. Anyone who follows Korean cinema will have noticed that Korean films often have a much bleaker point of view than those of other countries. Nevertheless it would be difficult to find one quite as unrelentingly dismal as A Mere Life (벌거숭이, Beolgeosungi). Encompassing all of human misery from the false support of family, marital discord, money worries, and the heartlessness of con men, A Mere Life throws just about everything it can at its everyman protagonist who finds himself trapped in a well of despair that not even death can save him from.

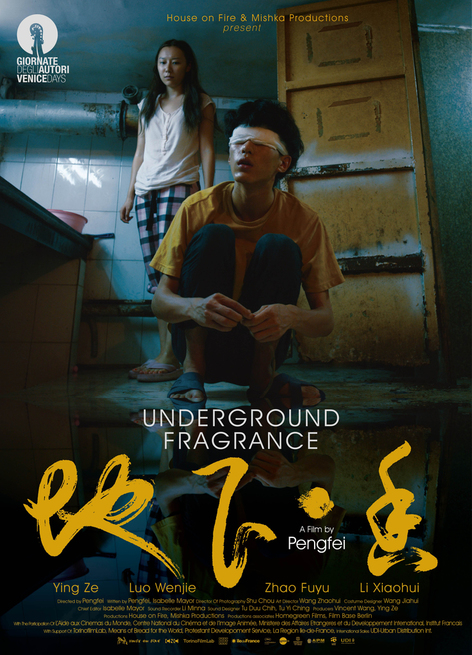

Anyone who follows Korean cinema will have noticed that Korean films often have a much bleaker point of view than those of other countries. Nevertheless it would be difficult to find one quite as unrelentingly dismal as A Mere Life (벌거숭이, Beolgeosungi). Encompassing all of human misery from the false support of family, marital discord, money worries, and the heartlessness of con men, A Mere Life throws just about everything it can at its everyman protagonist who finds himself trapped in a well of despair that not even death can save him from. The original Chinese title of recent Tsai Ming-liang collaborator (Song) Pengfei’s debut feature 地下・香 (dìxìa・xiāng) has an intriguing full stop in the middle which the English version loses, but nevertheless these two concepts “underground” and “fragance” become inextricably linked as the four similarly trapped protagonists desperately try to fight their way to better kind of life. Recalling Tsai’s dreamy symbolism, Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s romantic melancholy, and Jia Zhangke’s lament for the working man lost in China’s rapidly changing landscape, Pengfei’s film is nevertheless resolutely his own as it chases the ever elusive Chinese dream all the way from dank basements and ruined villages to the shiny high rise cities which promise a tomorrow they may never be able to deliver.

The original Chinese title of recent Tsai Ming-liang collaborator (Song) Pengfei’s debut feature 地下・香 (dìxìa・xiāng) has an intriguing full stop in the middle which the English version loses, but nevertheless these two concepts “underground” and “fragance” become inextricably linked as the four similarly trapped protagonists desperately try to fight their way to better kind of life. Recalling Tsai’s dreamy symbolism, Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s romantic melancholy, and Jia Zhangke’s lament for the working man lost in China’s rapidly changing landscape, Pengfei’s film is nevertheless resolutely his own as it chases the ever elusive Chinese dream all the way from dank basements and ruined villages to the shiny high rise cities which promise a tomorrow they may never be able to deliver. The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.

The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.

Review of Byun Young-joo’s Helpless (화차, Hwacha) first published by

Review of Byun Young-joo’s Helpless (화차, Hwacha) first published by  All those songs and rhymes you learnt as a child, somehow it’s strange to think that someone must have written them once, they seem to just exist independently. In Japan, the name behind many of these familiar tunes is Rentaro Taki – the first composer to set Japanese lyrics to European style “classical” music. It’s important to remember that even classical music was once contemporary, and along with the opening up of the nation during the Meiji era came a desire to engage with the “high culture” of other developed nations. The Tokyo Music School was founded in 1887 and Taki graduated from it just four years later in 1901. However, his career was to be a short one as his health gradually declined until he passed away of tuberculosis at just 23 years old. Bloom in the Moonlight (わが愛の譜 滝廉太郎物語, Waga Ai no Uta: Taki Rentaro Monogatari), also the title of one of his most well known and poignant songs, is the story of his musical career but also of the history of early classic music in Japan as the country found itself in a moment of extreme cultural shift.

All those songs and rhymes you learnt as a child, somehow it’s strange to think that someone must have written them once, they seem to just exist independently. In Japan, the name behind many of these familiar tunes is Rentaro Taki – the first composer to set Japanese lyrics to European style “classical” music. It’s important to remember that even classical music was once contemporary, and along with the opening up of the nation during the Meiji era came a desire to engage with the “high culture” of other developed nations. The Tokyo Music School was founded in 1887 and Taki graduated from it just four years later in 1901. However, his career was to be a short one as his health gradually declined until he passed away of tuberculosis at just 23 years old. Bloom in the Moonlight (わが愛の譜 滝廉太郎物語, Waga Ai no Uta: Taki Rentaro Monogatari), also the title of one of his most well known and poignant songs, is the story of his musical career but also of the history of early classic music in Japan as the country found itself in a moment of extreme cultural shift. Review of Jo Sung-hee’s The Phantom Detective (탐정 홍길동: 사라진 마을, Tamjung Honggildong: Sarajin Maeul) first published by

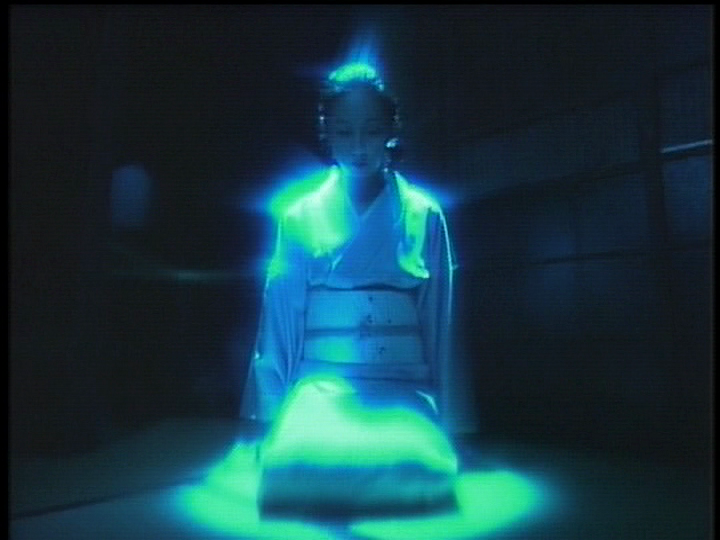

Review of Jo Sung-hee’s The Phantom Detective (탐정 홍길동: 사라진 마을, Tamjung Honggildong: Sarajin Maeul) first published by  Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.

Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.