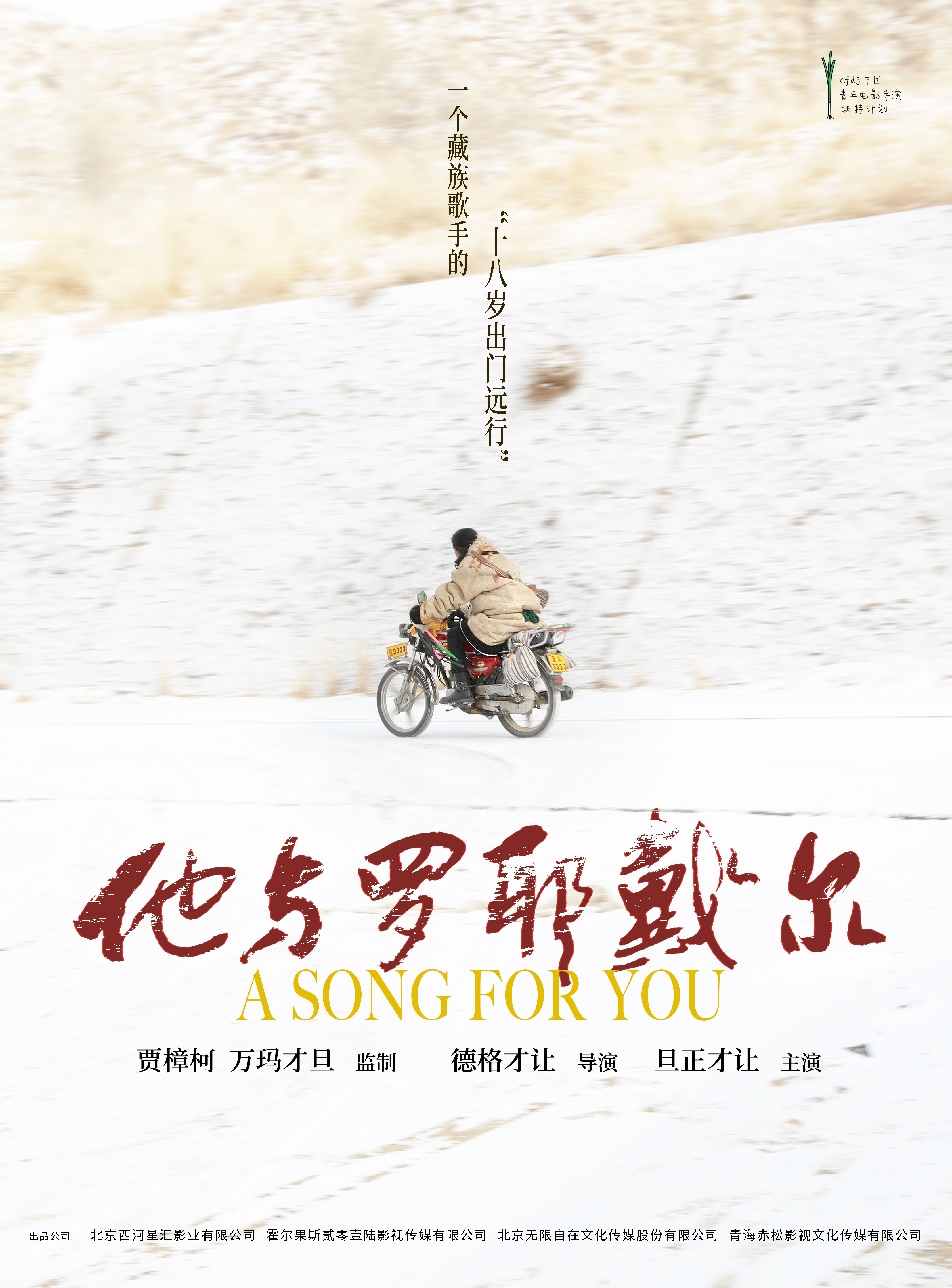

A resentful musician is confronted with the corrupting influences of modernity while trying to make it as a singer in the directorial debut from Dukar Tserang, A Song For You (他与罗耶戴尔, tā yǔ luó ye dài’ ěr) . Guided by the goddess of music, Ngawang travels from his home in the desert to the city and then still further while holding fast to the purity of his traditional art but perhaps begins to discover that evolution is not always betrayal while learning a little something from those he meets along the way even if his elliptical journey ends in its own kind of tragedy.

The son of a prominent musician in his home community, Ngawang (Damtin Tserang) longs to prove himself as a singer but is also rigid and uncompromising, getting into a fight with a friend of a friend who mocks him for stubbornly playing his traditional Zhanian zither when others have long since moved on to mandolin. Lhagyal sings the praises of popular musician Samdrup who seems to be something of a sore point to Ngawang, kickstarting a rant in which he accuses him of corrupting the art of Amdo singing with his modern evolutions such as drum machines and electronic backing. Lhagyal meanwhile argues that Samdrup has in fact saved their art and without his innovations no one would be at all interested in folk singing to begin with. The two men butt heads, but it’s Ngawang who ends up looking like a prig especially after he fails to place in the singing competition in which he’s come to perform after having arrogantly boasted of his talent.

It’s at the concert that he first lays eyes on a mysterious woman, another singer singing of the birth of Amdo music. Ngawang later comes to believe she is some kind of incarnation of the goddess of music, Loyiter, owing to the similarity she bears to an icon revealed once he accidentally breaks open a talisman his father had given him after having a tantrum that it clearly doesn’t work because he didn’t win the competition. The nameless woman advises that the reason Ngawang’s talent was not appreciated was because no one takes you seriously if you don’t have an album which is why he ropes in his feckless friend Pathar to help him get to Xining where it seems records are made.

It’s in the cities where he begins to feel his most severe pangs of culture shock, taken to a bar where he again spots the mysterious woman but this time she’s a rock singer named Yangchen who again begins helping him meet the right people to further his musical ambitions. The contrast between his songs which sing of the beauty of the natural world, and the highly corporatised, technologically advanced world of the music business couldn’t be more stark. Ngawang could not understand the words of Yangchen’s song even though he appreciated the melody because it was in Mandarin, while the design shop he uses for a poster ends up making an embarrassing typo in the Tibetan script which they are unable to read. Ngawang just wants to sing, but finds himself roped in to making a “video album” with an over zealous director who accuses him of having no presence and a lack of expression that make him unfilmable as a performer.

In any case, it isn’t just in the cities that modernity has begun to seep into the traditional. Stopping off on their road trip to deliver the sister of a man who ambushed them and then gave them a brief musical lesson to a monastery, Ngawang encounters a little boy begging in the street who seems to be homeless and alone. Noting the oversize Zhanian on his back he asks the boy for a song, which he sings in a melancholy rendition of life’s unfairness that some children have wealthy parents, some poor, and some none at all. Ngawang is embarrassed to realise he only has large notes, but the boy cheerfully pulls out a lanyard with a QR code Ngawang could have scanned to pay him via WeChat if only he had his phone. Throughout his wanderings Ngawang comes to a new understanding of the world around him which softens his rigidity while informing his music with a greater sense of openness even as he fails to notice a note of foreshadowing in Yangchen’s troubles only later realising he’s been away from home too long and there is always a price to be paid even if you serve the goddess of music. A light hearted musical odyssey and brief tour of the Tibetan plains, Dukar Tserang’s soulful road movie is an ode to singing for the love of it but also to openness and friendships, no matter how brief, made along the way.

A Song for You screened as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)