In some ways consciously and others not, we behave differently if we have an expectation of being observed than if we are confident we are alone. But the line between actions we think of as private and others public is often thinner than we assume and sometimes broken in moments of heightened emotion. A man sits and cries on a park bench, but he does so because he does not think anyone’s looking and feels himself alone though actually someone is watching. They often are, silently and at a distance that can itself be painful.

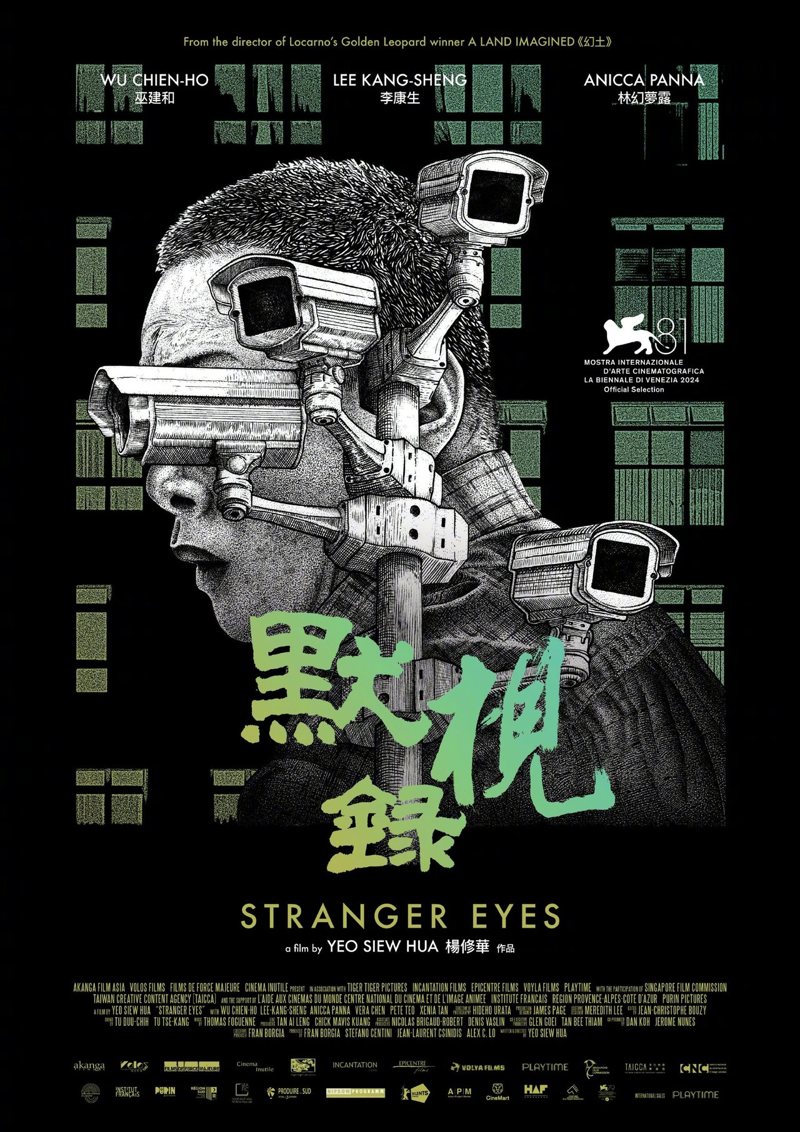

But then Yeo Siew Hua’s elliptical drama eventually suggests we are watched most by no stranger eyes than our own. Its “stalker”, Wu (Lee Kang-sheng), remarks that sometimes he feels as if he only watches himself an idea reinforced by the film’s continual doubling that suggests that we are in some ways caught between a series of overlapping timezones or entering a space of interactive memory. With echoes of Rear Window, the police accompany Shuping (Vera Chen), grandmother of a missing child, as she runs a pair of binoculars over the windows of her apartment block as seen from the balcony opposite while putting herself in the shoes of her observer. She stops on a young girl staring sadly from her window before beginning a strange dance that makes us wonder if Shuping is actually observing her younger self or if her own interiority simply colours what she is seeing.

Shuping, along with her son Juyang (Wu Chien-ho) and his wife Peiying (Anicca Panna), is scanning the horizon for traces of their missing child, Little Bo, while closely examining old videos looking for signs of anything untoward. The ubiquitous presence of these cameras reminds us that we are often being observed if accidentally and the use of these images could put us at risk. Shuping wants to put a video of the family at the park online but Peiying objects, insisting Bo should have the right to decide when she’s older though the implication is that someone could have seen Bo there and been minded to take her. In any case, the irony is there’s nothing useful either in the videos or, the family initially thinks, in the vast networks of CCTV cameras that exchange our privacy for supposed safety.

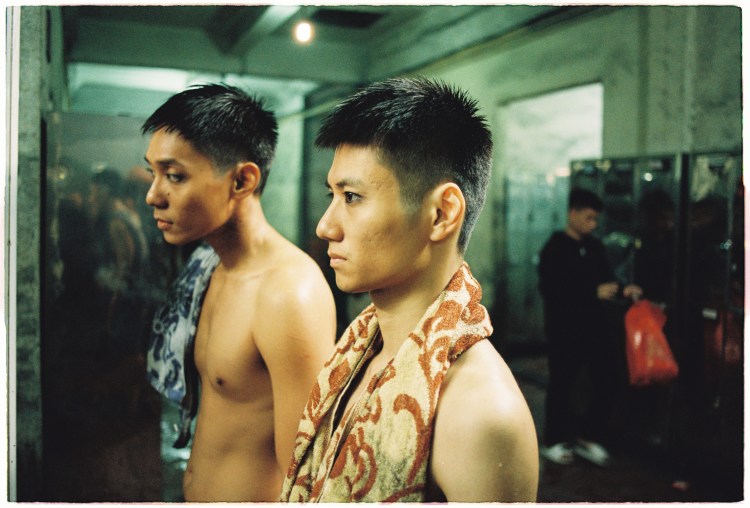

Wu relies firstly on his naked eyes, but then starts sending the family DVDs of videos he’s taken of them for unclear reasons but confronting Juyang and Peiying with the cracks in the foundations of their marriage along with the implication they are unfit parents. Juyang at one point simply walks off and leaves Bo sitting in a supermarket trolley while she cries her head off as if he were half hoping to be free of her. He in turn stalks another woman with a baby in a pushchair who turns to the side for a moment to help a man whose baby is crying, taking her eyes off her daughter long enough for Juyang to pick her up without her noticing. He could have easily have walked off with her, though you could hardly criticise this woman for simply having a chat with her daughter sitting just off to the side technically but perhaps not emotionally out of sight. Peiying meanwhile frets that Bo has been taken from her by some cosmic force because she didn’t love her enough and had considered an abortion before she was born again hinting at the fragility of the relationship between the parents who rarely occupy the same space and seem to live very parallel lives.

Ironically Peiying feels as if it is only Wu who has truly seen her for everything she is rather than solely as a mother or the persona she adopts as a live-streaming DJ. She says she feels as if Juyang only sees her as air, as if he looks right through her while he looks at other women and seems to feel trapped by domesticity or perhaps by Shuping whose obsessive love for Bo and occasionally overbearing grandmothering seems to annoy both parents in overstepping their boundaries. We observe them just as Wu does, making our judgements in our silence though in this case confident they do not see us and that we are not ourselves currently being observed. But this confidence may also be painful to an observer such as Wu who wants to penetrate the screen while also interacting with his own sense of regret and is unable to make himself visible or express what he feels outside outside of the ghostly act of observation. The watchful soul observes itself as reflected in others who exist only in a world lost to them.

Stranger Eyes screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival

Original trailer (English subtitles)