Throughout the Angel Guts series, a woman named Nami and a man called Muraki somehow come together and explore the complex interplay between men and women. In his first directorial effort adapting his own source material Takashi Ishii takes the series in a dreamlike and melancholic direction, shaving off some of its harsh edges but also fully indulging in a nourish sense of fatalistic nihilism. They may not know it, but these are of course two people dancing on the edge of an abyss with no place to go back to.

In fact, the very nature of sleeping and waking has become blurred for exhausted nurse Nami (Mayako Katsuragi) despite the heart monitors bleeping all around her. She thinks of her boyfriend, Kenji (Hirofumi Kobayashi), who takes erotic photographs he claims are all of her, but doesn’t seem altogether sincere under the red lights of his darkroom as he repeatedly asks Nami to pose for him. Her patients, meanwhile, often call her for reasons that aren’t strictly medical. Trying to stay awake on her rounds, she’s violently accosted by two men only for her supervisor to insist that the room is currently vacant. Perhaps Nami dreamed it, though the experience is traumatic enough for her to go home early and inadvertently catch Kenji with one of his models in their apartment. He tells the model that he’s not interested in marriage, though she asks about his “wife”, adding to Nami’s pain and confusion on hearing him describe their relationship so casually.

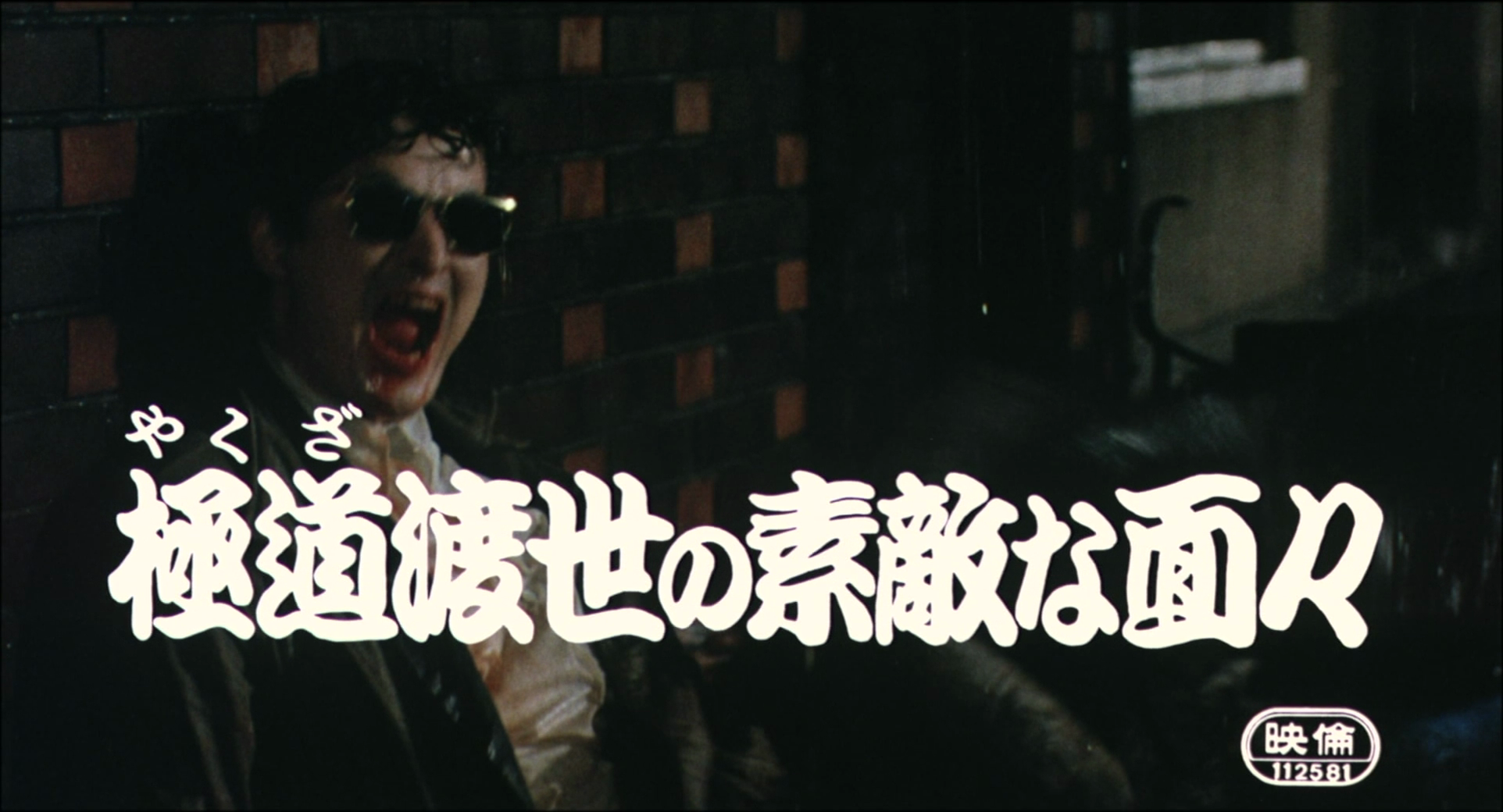

Meanwhile, Muraki is dreaming more literally. He imagines himself fondling a woman who runs a bar before being coaxed towards an ominous-looking bath that presages his visit to the love hotel with Nami. We hear that his wife has left him, and that he’s being hounded by debt collectors while on the run after embezzling a large amount of money from his company believing it was “easy” and that no one would really notice or care. This is, after all, an age of excess that would only later become known as the Bubble era, though the bubble has certainly burst for Muraki. Ironically enough, he’ll meet a sticky end after getting on the wrong side of a man driving a Mercedes (Akira Emoto) as if he were literally gunned down by a rampant status-driven consumerism. The man looks and behaves like a yakuza, but is unusually reckless even if hotheaded in believing he’s been treated with an insufficient amount of respect for a man with a fancy ride.

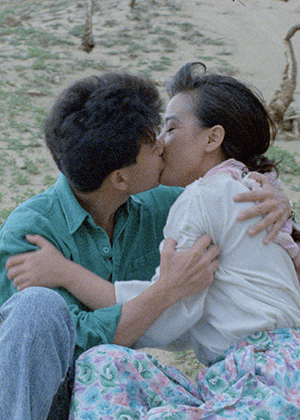

Nami too is hit by a car, literally colliding with Muraki who first thinks he’s killed her and somehow made his situation even worse. On realising she’s still alive, though having measured her pulse with his thumb which proves nothing other than his own heart is still beating, he decides to assault her instead later explaining that he just wanted warmth which only makes him seem even more pathetic. Nami, however, fights back wielding a plank like a phallic object and taking back control only for Muraki to keep her prisoner in an abandoned building. There is, however, something that develops between the pair with the rain beating down and isolating them from the outside world. Stuck in this liminal place, they each accept that they have no place to go back to and therefore have only each other.

But there is really no salvation in this harsh world and nowhere to go which is why Muraki is stopped in his tracks and Nami condemned to a perpetual waiting even if she’s found a kind of freedom dancing alone in her limbo state and under the colourful neon lights of the abandoned warehouse. Asked what he most feared in this world, a character in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks replied “the possibility that love is not enough,” an idea which seems to echo through Ishii’s melancholy urban landscapes, all garish neon offering the semblance of warmth but always drenched in rain. Even interior spaces seem misty and uncertain, leading us into a kind of dream space otherwise indistinguishable from waking life. Muraki and Nami are, however, evidently on different paths and unlikely to find their way back to each other even if either of them manage to break free of their respective dead ends.

Angel Guts: Red Vertigo is available as part of The Angel Guts Collection released on blu-ray 23rd February courtesy of Third Window Films.