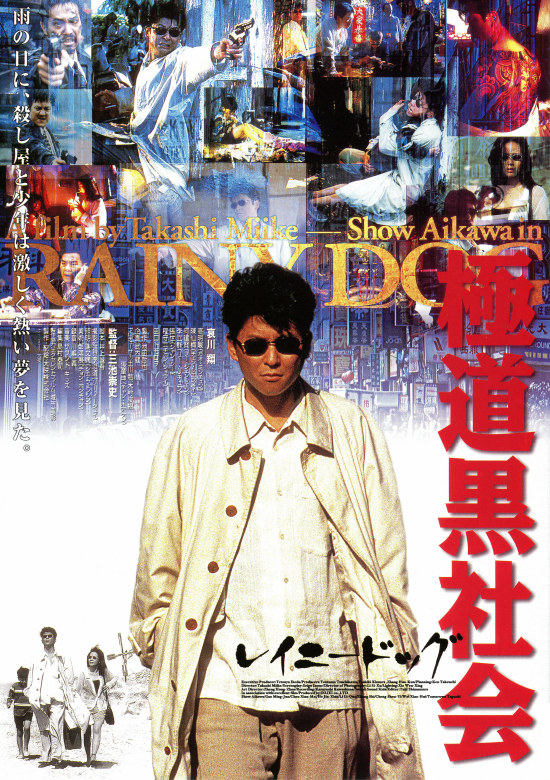

They say dogs get disorientated by the rain, all those useful smells they use to navigate the world get washed away as if someone had suddenly crumpled up their internal maps and thrown them in the waste paper bin. Yuji (Show Aikawa), the hero of Rainy Dog (極道黒社会, Gokudo Kuroshakai) – the second instalment in what is loosely thought of as Takashi Miike’s Black Society Trilogy, appears to be in a similar position as he hides out in Taipei only to find himself with no home to return to. Miike is not generally known for contemplative mood pieces, but Rainy Dog finds him feeling introspective. A noir inflected, western inspired tale of existential reckoning, this is Miike at his most melancholy but perhaps also at his most forgiving as his weary hitman lays down his burdens to open his heart only to embrace the cold steel of his destiny rather than the warmth of his redemption.

They say dogs get disorientated by the rain, all those useful smells they use to navigate the world get washed away as if someone had suddenly crumpled up their internal maps and thrown them in the waste paper bin. Yuji (Show Aikawa), the hero of Rainy Dog (極道黒社会, Gokudo Kuroshakai) – the second instalment in what is loosely thought of as Takashi Miike’s Black Society Trilogy, appears to be in a similar position as he hides out in Taipei only to find himself with no home to return to. Miike is not generally known for contemplative mood pieces, but Rainy Dog finds him feeling introspective. A noir inflected, western inspired tale of existential reckoning, this is Miike at his most melancholy but perhaps also at his most forgiving as his weary hitman lays down his burdens to open his heart only to embrace the cold steel of his destiny rather than the warmth of his redemption.

Yuji’s day job seems to be hulking pig carcasses around at the meat market but he’s also still acting as a button man for the local Taiwanese mob while he lies low and avoids trouble in Taipei following some kind of incident with his clan in Japan. Receiving a call to the effect that following a change of management it will never be safe for him to go home, Yuji is as lost as a dog after the rain but if there’s one thing he hadn’t banked on it was the appearance of a rather sharp Taiwanese woman who suddenly introduces him to a mute little boy who is supposedly his son. Yuji is not the fatherly type and does not exactly take to his new responsibilities. He half remembers the woman, but can’t place her name and isn’t even sure he ever slept with her in the first place. Nevertheless, Ah Chen follows Yuji around like a lost little puppy.

Two more meetings will conspire to change Yuji’s life – firstly a strange, besuited Japanese man (Tomorowo Taguchi) who seems to snooze on rooftops in a sleeping bag and is intent on getting the drop of Yuji for undisclosed reasons, and the proverbial hooker with a heart of gold (and a fancy computer for running an internet blog) with whom he will form a temporary makeshift family. Getting mixed up in something he shouldn’t Yuji’s cards are numbered, but then it couldn’t have been any other way.

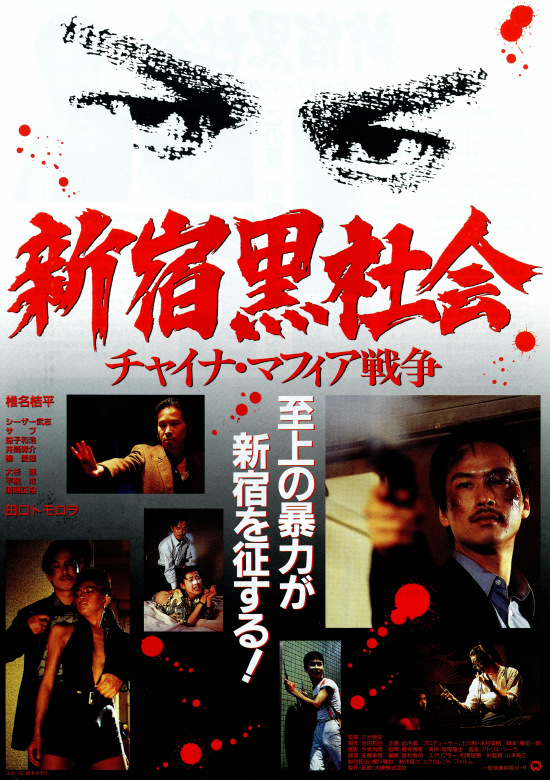

As in Shinjuku Triad Society, Miike returns to the nature of family and of the tentative bonds which emerge between people who have been rejected from mainstream society. Yuji is a displaced person, forced out of his homeland and lost in a foreign city. Though he appears to have a good grasp of the local language, the landscape confuses him as he wanders through it like the man with no name, adrift and permanently shielded by his sunglasses. The Taiwanese gangster he’s been freelancing for repeatedly describes him as “like a son” despite the fact that they seem to be around the same age but it’s clear that he could have Yuji eliminated in a heartbeat if he found he’d outlived his usefulness.

Similarly, Yuji does not immediately jump into a paternal mindset when presented with this strangely cheerful young boy. Eventually he lets him come out of the rain and presents him with a towel, greeting him with the words “you’re not a dog” but subsequently abandons him for what seems like ages during his time with the prostitute, Lily, who describes his tattoos as beautiful and shares his dislike of the intense Taipei rain. Asked if she’s ever considered going somewhere sunnier, Lily admits that she has but the fear that perhaps it would all be the same (only less wet) has put her off. Perhaps it’s better to live in hope, than test it and find out it was misplaced.

Gradually, Yuji begins to a least develop a protective instinct for Ah Chen as well as some kind of feeling for Lily which leads him to carry out another hit in order to give her the money to escape on the condition that she take Ah Chen with her. However the trio get ambushed on their way out ending up at a beach leaving them with nowhere left to run, signalling the impossibility of getting off this inescapable island. Just when it seems all hope is lost, Ah Chen finds a buried scooter which he and Lilly begin to dig up. Eventually, Yuji joins them, fully confirming his commitment to the mini family they’ve accidentally formed as they work together to build themselves a way out. Yuji’s decision separate from them and return to the world of crime, albeit temporary, will be a final one in which he, by accident or design, rejects the possibility of a more conventional family life with Ah Chen and Lilly for the destiny which has been dogging him all along.

Birth and death become one as Yuji regains his humanity only to have it taken from him by a man exactly mirroring his journey. There are no theatrics here, this is Miike in paired down, naturalistic mode willing to let this classic story play out for all that it is. Working with a Taiwanese crew and capturing the depressed backstreet world of our three outcasts trapped by a Taipei typhoon for all of its existential angst, Rainy Dog is Miike at his most melancholic, ending on a note of futility in which all hope for any kind of change or salvation has been well and truly extinguished.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of  You might think there could be no more diametrically opposed directors than Akira Kurosawa – best known for his naturalistic (by jidaigeki standards anyway) three hour epic Seven Samurai, and Nobuhiko Obayashi whose madcap, psychedelic, horror musical Hausu continues to over shadow a far less strange career than might be expected. However,

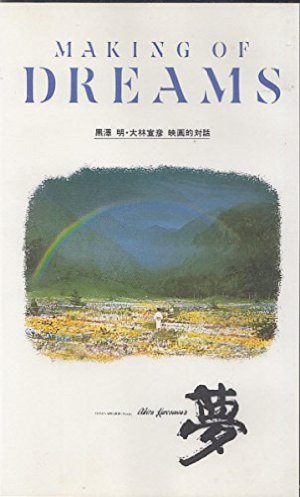

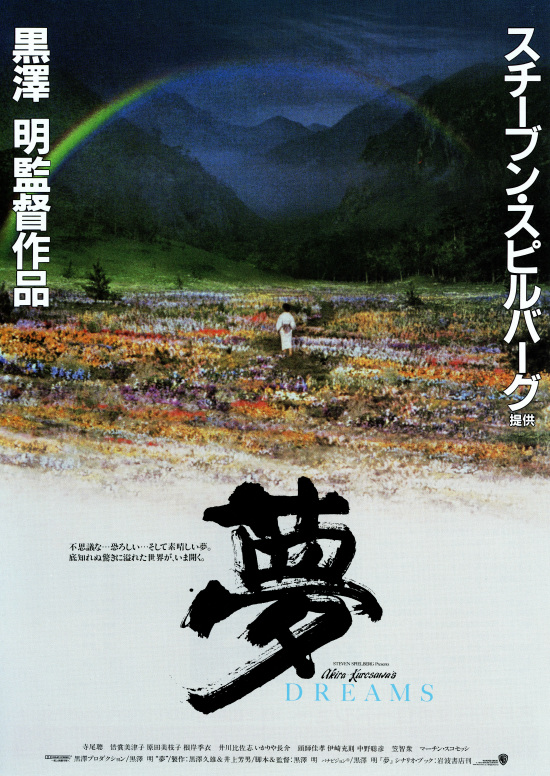

You might think there could be no more diametrically opposed directors than Akira Kurosawa – best known for his naturalistic (by jidaigeki standards anyway) three hour epic Seven Samurai, and Nobuhiko Obayashi whose madcap, psychedelic, horror musical Hausu continues to over shadow a far less strange career than might be expected. However,  Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced.

Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced. Looking back, at least to those of us of a certain age, the late ‘90s seem like a kind of golden era, largely free from the economic and political strife of the current world, but the cinema of that time is filled with the anxiety of the young – particularly in Japan, still mired in the wake of the post-bubble depression. Toshiaki Toyoda’s Pornostar (ポルノスター, retitled Tokyo Rampage for the US release) (not quite what it sounds like), is just such a story. Its protagonist, Arano (Chihara Junia, unnamed until the closing credits), stalks angrily through the busy city streets which remain as indifferent to him as he is to them. Though his wandering appears to have no especial purpose, Arano seethes with barely suppressed rage, nursing sharpened daggers waiting to plunge into the hearts of “unnecessary” yakuza.

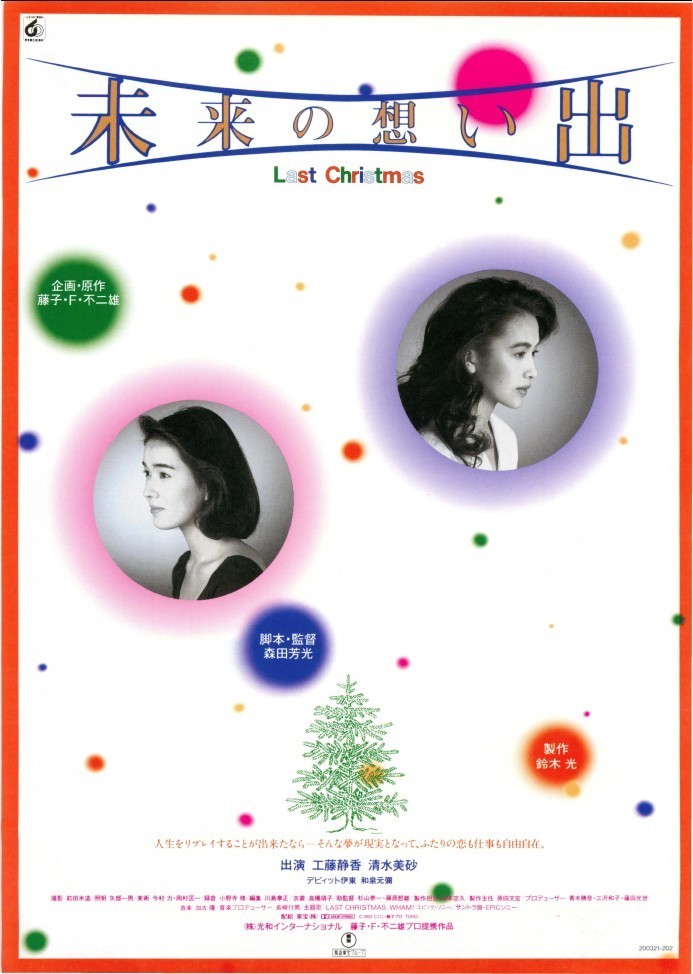

Looking back, at least to those of us of a certain age, the late ‘90s seem like a kind of golden era, largely free from the economic and political strife of the current world, but the cinema of that time is filled with the anxiety of the young – particularly in Japan, still mired in the wake of the post-bubble depression. Toshiaki Toyoda’s Pornostar (ポルノスター, retitled Tokyo Rampage for the US release) (not quite what it sounds like), is just such a story. Its protagonist, Arano (Chihara Junia, unnamed until the closing credits), stalks angrily through the busy city streets which remain as indifferent to him as he is to them. Though his wandering appears to have no especial purpose, Arano seethes with barely suppressed rage, nursing sharpened daggers waiting to plunge into the hearts of “unnecessary” yakuza. Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era. All those songs and rhymes you learnt as a child, somehow it’s strange to think that someone must have written them once, they seem to just exist independently. In Japan, the name behind many of these familiar tunes is Rentaro Taki – the first composer to set Japanese lyrics to European style “classical” music. It’s important to remember that even classical music was once contemporary, and along with the opening up of the nation during the Meiji era came a desire to engage with the “high culture” of other developed nations. The Tokyo Music School was founded in 1887 and Taki graduated from it just four years later in 1901. However, his career was to be a short one as his health gradually declined until he passed away of tuberculosis at just 23 years old. Bloom in the Moonlight (わが愛の譜 滝廉太郎物語, Waga Ai no Uta: Taki Rentaro Monogatari), also the title of one of his most well known and poignant songs, is the story of his musical career but also of the history of early classic music in Japan as the country found itself in a moment of extreme cultural shift.

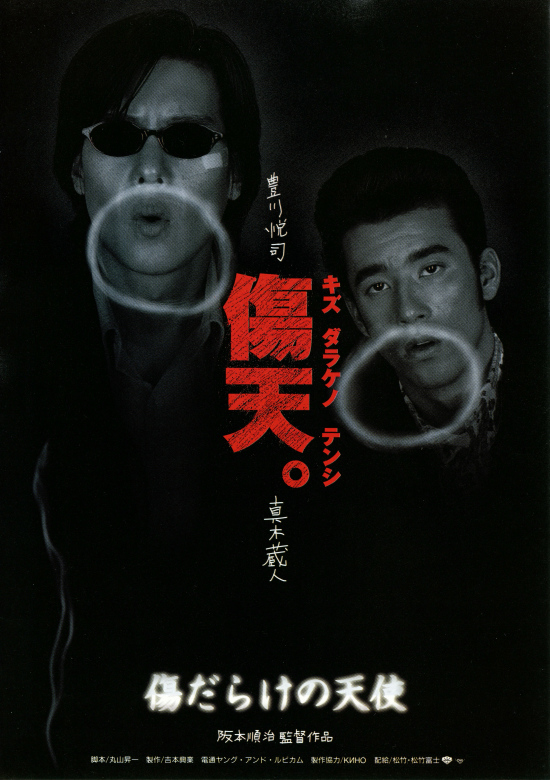

All those songs and rhymes you learnt as a child, somehow it’s strange to think that someone must have written them once, they seem to just exist independently. In Japan, the name behind many of these familiar tunes is Rentaro Taki – the first composer to set Japanese lyrics to European style “classical” music. It’s important to remember that even classical music was once contemporary, and along with the opening up of the nation during the Meiji era came a desire to engage with the “high culture” of other developed nations. The Tokyo Music School was founded in 1887 and Taki graduated from it just four years later in 1901. However, his career was to be a short one as his health gradually declined until he passed away of tuberculosis at just 23 years old. Bloom in the Moonlight (わが愛の譜 滝廉太郎物語, Waga Ai no Uta: Taki Rentaro Monogatari), also the title of one of his most well known and poignant songs, is the story of his musical career but also of the history of early classic music in Japan as the country found itself in a moment of extreme cultural shift. Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture

Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture  Review of Kitano’s Kids Return first published by

Review of Kitano’s Kids Return first published by  Review of Takeshi Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea – first published by

Review of Takeshi Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea – first published by