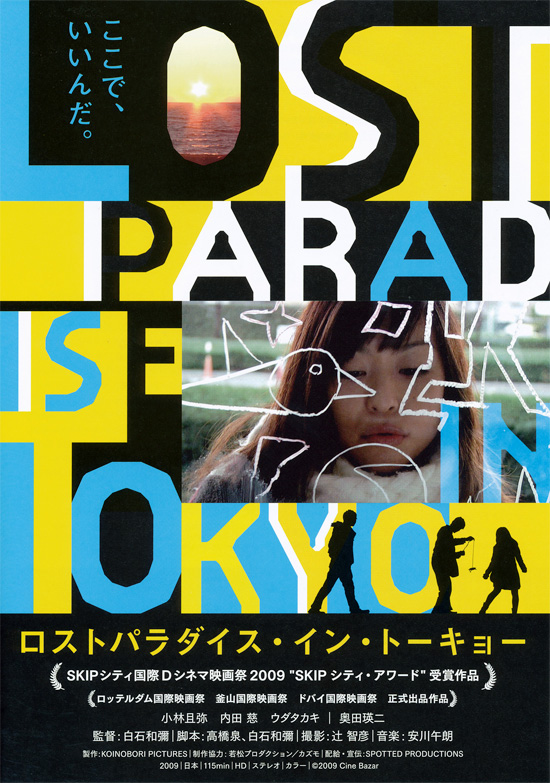

Happiness seems an elusive concept for a group of three Tokyoites each chasing unattainable dreams of freedom in a constraining society. The debut feature from Kazuya Shiraishi, Lost Paradise in Tokyo (ロストパラダイス・イン・トーキョー) is much more forgiving of its central trio than many an indie foray into the forlorn hopes of modern youth but neither does it deny the difficulty of living in such frustrating circumstances.

Happiness seems an elusive concept for a group of three Tokyoites each chasing unattainable dreams of freedom in a constraining society. The debut feature from Kazuya Shiraishi, Lost Paradise in Tokyo (ロストパラダイス・イン・トーキョー) is much more forgiving of its central trio than many an indie foray into the forlorn hopes of modern youth but neither does it deny the difficulty of living in such frustrating circumstances.

Mikio (Katsuya Kobayashi) has a soul crushing job as a telephone real estate salesman at which he’s not particularly good and is often subject to trite rebukes from a patronising boss who breaks off from the morning mantra to enquire how the funeral went for Mikio’s recently deceased father only to then remark that Mikio’s dad won’t be able to rest in peace unless Mikio bucks up at work. At home, Mikio has just become the sole carer for his older brother, Saneo (Takaki Uda), who has severe learning difficulties and has been kept a virtual prisoner at home for the last few years. Saneo, however, is still a middle-aged man with a middle-aged man’s desires and so Mikio decides to hire a prostitute to help meet his sexual needs.

“Morin-chan” (Chika Uchida) as she lists herself, is also an aspiring “underground idol” known as Fala who makes ends meet through sex work. Depite Mikio’s distaste for the arrangement, Morin is a good companion to Saneo, calming him down and helping to look after him while Mikio is at work. In her life as Fala, Morin is also the subject of a documentary about underground idols and when the documentarians stumble over her double life they make her a surprising offer – allow herself to be filmed and they will give her a vast amount of money which might enable her to achieve her dream of buying a paradise island.

Mikio is doing the best he can but is as guilty of societal stigma relating to the disabled as anyone else and his guilt in feeling this way about his own brother coupled with the resentment of being obliged to care for him has left him an angry, frustrated man. Asked at work if he has any siblings Mikio lies and says he’s an only child, denying his brother’s existence rather than risk being associated with disability. At home he can’t deny him but neither can he be around to keep an eye on him all day and so there have been times when he’s had to literally (rather than metaphorically) lock his brother away.

Longing for freedom, Mikio wants out of his stressful, soul destroying job and the responsibility of caring for his brother while Morin is trapped in the world of “underground idols” who are still subject to the same constraints as the big studio stars only without the fame, money, or opportunities. As one of the documentarians points out, Morin (or Fala) is really a little old for the underground idol scene, her days limited and dreams of mainstream success probably unattainable. For as long as she can remember she’s dreamed of a paradise “island” where she can she live freely away from social constraints and other people’s disapproval.

Mikio had got used to thinking of his brother as a simple creature whose life consisted of needs and satisfactions but the entry of Morin into their lives forces him to consider what it is that his brother might regard as “happiness” and if such a thing can ever exist for him. Morin wants the three of them to go her paradise island where Saneo can live his life freely away from the unforgiving eyes of society but unbeknownst to any of them they may have already found a kind of paradise without realising.

Later Mikio admits that he and his father were content to lock Saneo away because they feared they wouldn’t understand him. Once Saneo hurt someone, not deliberately, but through being unable to express himself in the normal way and not fully understanding that his actions would cause someone else pain. Rather than deal with the problem, Mikio’s father decided to hide his son away – less to protect Saneo from himself, than in wanting to avoid the stigma resulting from his existence. Saneo, however, may not be able to express himself in ways that others will understand but is still his own person with his own hopes and ideas as his final actions demonstrate. Only once each has come to a true understanding of themselves and an abandonment of fantasy can there be a hope of forward motion, finally rediscovering the “lost paradise” that the city afforded them but they were too blind to see.

Available to stream in most territories via FilmDoo.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

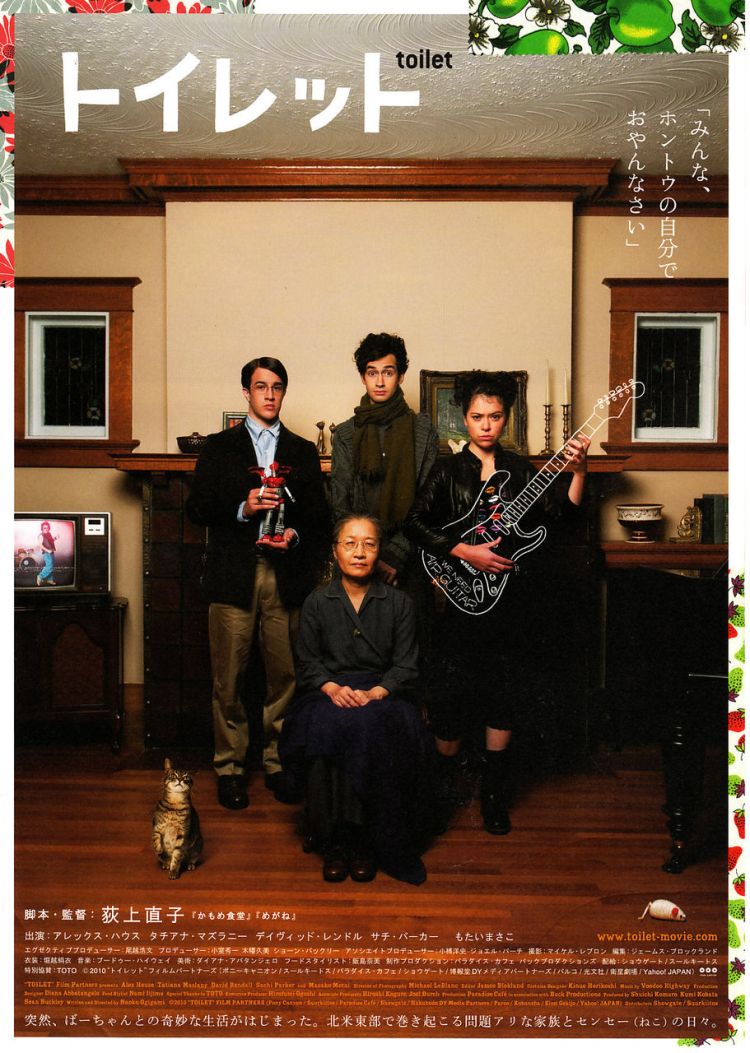

Yasushi Sato, a Hakodate native, has provided the source material for some of the best films of recent times including Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There and Nobuhiro Yamashita’s

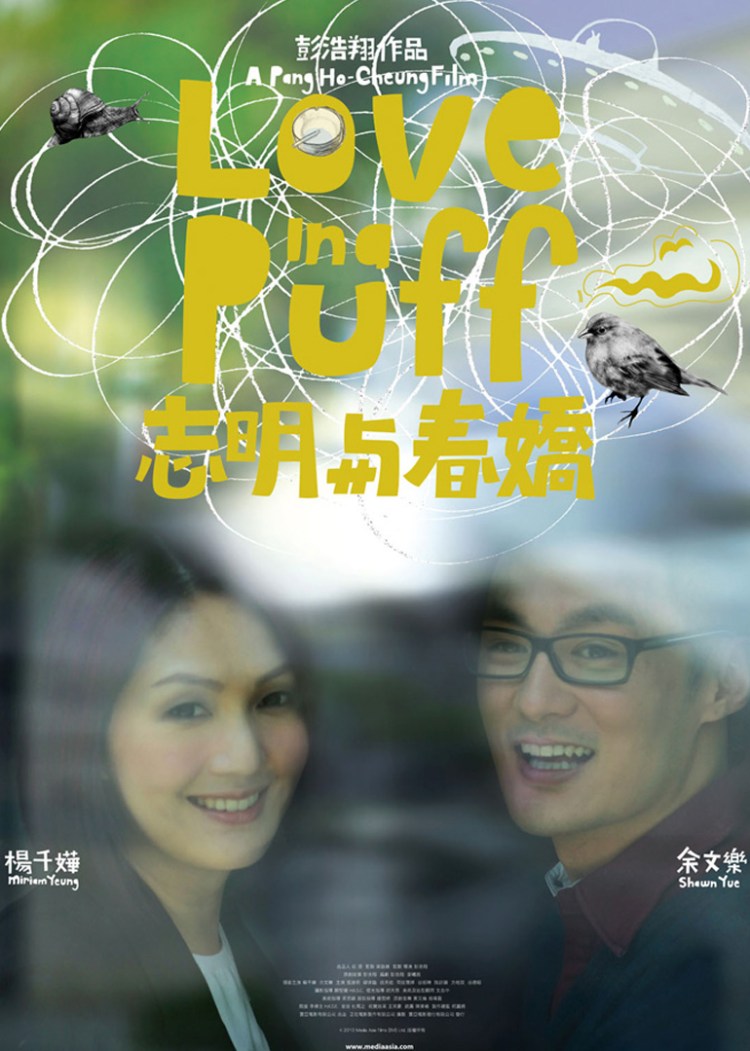

Yasushi Sato, a Hakodate native, has provided the source material for some of the best films of recent times including Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There and Nobuhiro Yamashita’s  Smokers. Is there a more maligned, ostracised group in the modern world? Considering the rapid pace at which their “harmless” pastime has become unacceptable, you can understand why they might feel particularly put out – literally, as they find themselves taking refuge in designated smoking areas or perhaps back allies where it seems no one’s looking. For all the nostalgia about how easy it was to strike up a friendship with a stranger just by asking for a light, it is also important to remember that smoking is not so “harmless” after all and there are reasons why smokers are asked to keep their activities amongst those who’ve also decided to ignore the warnings. The Smoking Ordinance, oddly enough, may have accidentally boosted the social potential of a smoke as those eager for a puff are given additional reasons to spend time together in an enclosed space, building a sense of community through nicotine addiction.

Smokers. Is there a more maligned, ostracised group in the modern world? Considering the rapid pace at which their “harmless” pastime has become unacceptable, you can understand why they might feel particularly put out – literally, as they find themselves taking refuge in designated smoking areas or perhaps back allies where it seems no one’s looking. For all the nostalgia about how easy it was to strike up a friendship with a stranger just by asking for a light, it is also important to remember that smoking is not so “harmless” after all and there are reasons why smokers are asked to keep their activities amongst those who’ve also decided to ignore the warnings. The Smoking Ordinance, oddly enough, may have accidentally boosted the social potential of a smoke as those eager for a puff are given additional reasons to spend time together in an enclosed space, building a sense of community through nicotine addiction. Koji Wakamatsu made his name in the pink genre where artistic flair and political messages mingled with softcore pornography and the rigorous formula of the genre. Wakamatsu rarely abandoned this aspect of his work but in adapting a well known story by Japan’s master of the grotesque Edogawa Rampo, Wakamatsu redefines his key concern as sex becomes currency, a kind of trade and power game between husband and wife. Caterpillar (キャタピラー), aside from its psychological questioning of marital relations, is a clear anti-war rallying call as a small Japanese village finds itself brainwashed into sacrificing its sons for the Emperor, never suspecting all their sacrifices will have been in vain when the war is lost and wounded men only a painful reminder of wartime folly.

Koji Wakamatsu made his name in the pink genre where artistic flair and political messages mingled with softcore pornography and the rigorous formula of the genre. Wakamatsu rarely abandoned this aspect of his work but in adapting a well known story by Japan’s master of the grotesque Edogawa Rampo, Wakamatsu redefines his key concern as sex becomes currency, a kind of trade and power game between husband and wife. Caterpillar (キャタピラー), aside from its psychological questioning of marital relations, is a clear anti-war rallying call as a small Japanese village finds itself brainwashed into sacrificing its sons for the Emperor, never suspecting all their sacrifices will have been in vain when the war is lost and wounded men only a painful reminder of wartime folly. Japan was a strange place in the early ‘90s. The bubble burst and everything changed leaving nothing but confusion and uncertainty in its place. Tokyo, like many cities, however, also had a fairly active indie music scene in part driven by the stringency of the times and representing the last vestiges of an underground art world about to be eclipsed by the resurgence of studio driven idol pop. Bandage (Bandage バンデイジ) is the story of one ordinary girl and her journey of self discovery among the struggling artists and the corporate suits desperate to exploit them. One of the many projects scripted and produced by Shunji Iwai during his lengthy break from the director’s chair, Bandage is also the only film to date directed by well known musician and Iwai collaborator Takeshi Kobayashi who evidently draws inspiration from his mentor but adds his own particular touches to the material.

Japan was a strange place in the early ‘90s. The bubble burst and everything changed leaving nothing but confusion and uncertainty in its place. Tokyo, like many cities, however, also had a fairly active indie music scene in part driven by the stringency of the times and representing the last vestiges of an underground art world about to be eclipsed by the resurgence of studio driven idol pop. Bandage (Bandage バンデイジ) is the story of one ordinary girl and her journey of self discovery among the struggling artists and the corporate suits desperate to exploit them. One of the many projects scripted and produced by Shunji Iwai during his lengthy break from the director’s chair, Bandage is also the only film to date directed by well known musician and Iwai collaborator Takeshi Kobayashi who evidently draws inspiration from his mentor but adds his own particular touches to the material. The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point.

The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point.