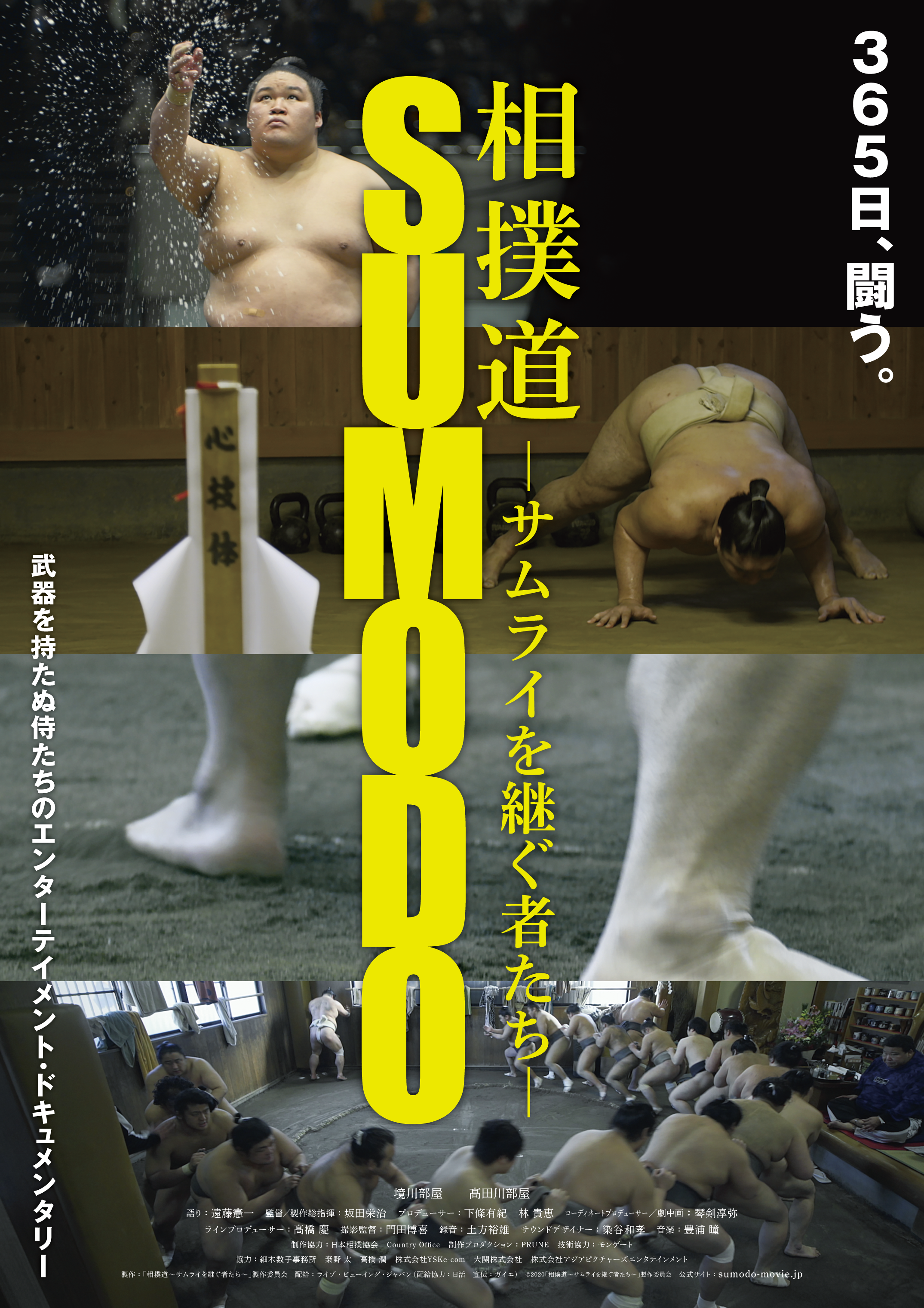

“Every day is a traffic accident” according to a sumo wrestler describing the motion of two men colliding each trying to shove the other out of a protected area. Often regarded as a quintessentially Japanese combat sport, sumo has also come in for its share of misconceptions sometimes mocked or dismissed as a pastime popular mainly among the elderly or else a source of comedy in which in two large men clumsily grapple with each other. It’s precisely these unfair stereotypes that Eiji Sakata’s documentary SUMODO ~The Successors Of Samurai~ (相撲道~サムライを継ぐ者たち~, Sumodo ~Samurai o tsugu monotachi~) hopes to correct in gaining unprecedented access to the usually secretive world of professional sumo.

He does this largely through focussing on two very different sumo stables and two key tournaments, one at New Year and the other in May. Though he interviews several of the rikishi at each, he adopts two main subjects who eventually clash in the ring but otherwise avoids clear narrative for an overview of what it’s like to live as a professional sumo wrestler in the present day which is to say a lifestyle that is largely unchanged over hundreds of years. Perhaps surprisingly, he even stops to appreciate the way in which a sumo tournament has also become something of a fashion show in which an audience comes expressly to appreciate the traditional kimono modelled by the rikishi as they make their way towards the auditorium. Living communally at the stable where they train, sumo wrestlers are expected to dress in traditional clothing at all times and wear their hair in a traditional style.

Their diet is of course strictly monitored in order to help them maintain their weight. At the second of the stables, Takadagawa, food is a particular issue one rikishi stating that the high quality of the cuisine is one reason he chose to train there and while the chef explains that he keeps the vegetable content high and is keen to encourage healthy, nutritious eating the stable master is also determined that the meals be tasty rather than an austere exercise in body building. Sumo wrestlers do nevertheless eat quite a lot, the director perhaps regretting his decision to take the rikishi from the first stable Sakaigawa out for Korean barbecue when they literally eat the place out of its entire stock of meat generating a bill for US$8000 for under 50 people.

Even so, despite their size the sumo wrestlers are necessarily extremely fit and spend much of their time deliberately building muscle. Whereas Sakaigawa is more traditional in its rather austere outlook, the master at Takadagawa, a former rikishi himself, explains that the sport has in a sense changed in keeping with the modern society in that he’s moved away from an aggressive coaching style that some might regard as bullying or harassment towards something kinder that values endurance and perseverance. The contrast is also visible in the choice of the two protagonists, Goeido being much more the traditional image of a sumo wrestler with his rather intense demeanour and emphasis on manly stoicism, whereas Ryuden is a surprisingly cheerful man with a joyful laugh and aura of serenity.

Yet even Goeido describes the tournament process as mentally and physically exhausting despite fighting only one bout a day. At one particular tournament he tears a muscle in his upper arm but refuses to have it strapped unwilling to expose his area of weakness to an opponent later criticising younger wrestlers for making too much fuss over injury advising them that they should remain stoical without complaint like “true men”. Despite his more progressive coaching style, the master of Takadagawa says something similar in regarding injuries as tests from god or else a clear sign that more training is necessary. Ryuden himself suffered recurrent problems from a broken pelvis that saw him temporarily demoted but worked his way back to health by concentrating on “the basics”, later advising younger rikishi that there’s no hurry what’s important is to keep pushing through and avoid giving up too easily. The spirit of sumo, however, never changes at least according to the closing text. Illuminating the sport’s ancient history and ties to shinto ritual through a brief animated sequence, Sakata is most interested in the everyday lives of sumo wrestlers and the physical, emotional toll the sport can take on their lives as they push their bodies to the absolute limit of their capabilities.

SUMODO ~The Successors Of Samurai~ screens in Canberra (Oct. 31), Perth (Nov. 7), Brisbane (Nov. 14), Melbourne (Nov. 20/23) and Sydney (Nov. 26/28) as part of this year’s Japanese Film Festival Australia.

Original trailer (English subtitles)