Review of Byun Young-joo’s Helpless (화차, Hwacha) first published by UK Anime Network

Review of Byun Young-joo’s Helpless (화차, Hwacha) first published by UK Anime Network

Can you ever really know another person? Everything you think you know about the people closest to you is founded on your own desire to believe what they’ve told you is the fundamental truth about themselves, yet you’ll never receive direct proof one way or the other. Byun Young-joo’s Helpless is based on Miyuki Miyabe’s popular novel Kasha (available in an English translation by Alfred Birnbaum under the title All She Was Worth) which literally means “fiery chariot” and is the name given to a subset of yokai who feed on the corpses of those who have died after accumulating evil deeds, which may tell you something about the direction this story is headed. After his fiancée suddenly disappears, one man discovers the woman he loved was not who she claimed to be, but perhaps also discovers that she was exactly who he thought she was all along.

Mun-ho (Lee Sun-kyun) and Seon-young (Kim Min-hee) are newly engaged and on their way to deliver a wedding invite to his parents in person. They seem bubbly and excited, still cheerful in the middle of a long car journey. It’s doubly surprising therefore when Mun-ho returns to the car after stopping at a service station to find that Seon-young has disappeared. Seon-young is not answering her phone and has left her umbrella behind despite the pouring rain which only leaves Mun-ho feeling increasingly concerned. His only clue is her distinctive hair clip lying on the floor of the petrol station toilet. Reporting his fiancée’s disappearance to the police, Mun-ho is more or less fobbed off as they come to the obvious conclusion that the couple must have argued and Seon-young has simply left him, as is her right. Confused, hurt, and worried Mun-ho turns to his old friend, Jong-geun (Cho Seong-ha), a recently disgraced ex-policeman, to help him understand what exactly has happened to the woman he thought he loved.

Mun-ho, helpless as the title, has no idea what might have transpired – has she been abducted? Was she in trouble, was someone after her? Did she simply get cold feet as the policemen suggested? A trip to Seon-young’s apartment reveals the place has been pretty thoroughly turned over leaving little trace behind, the entire apartment has even been swept for fingerprints in chillingly methodical fashion. Another clue comes from a close friend who’d been looking into the couple’s finances and found some improprieties in Seon-young’s past which he’s surprised she wouldn’t have mentioned. Perhaps she was embarrassed or ashamed of her credit history, but running out onto the motorway in the pouring rain without even stopping to pick up an umbrella seems like a massive overreaction for such an ordinary transgression.

What transpires is a tale of identity theft, vicious loan sharks, parental neglect, and the increasingly lonely, disconnected society which opens doors for the predatory. Usurious loans become an ironic recurring theme as they ruin lives left, right and centre. Following the financial crash, a father takes out a loan from gangsters to support his business but promptly goes missing. His wife is so distraught that she becomes too depressed to care for their daughter who ends up in a catholic orphanage. Gangsters have their own rules, the debt passes to the girl, young as she is, who is then forced to pay in non-monetary services until she finally escapes only to discover the torment is not yet over. Meanwhile, another woman takes out a series of loans to cover credit card debt and is forced to declare bankruptcy, left only with a lingering sense of shame towards her ailing mother who then dies in a freak accident leaving her a windfall inheritance which she uses to buy a fancy headstone for the woman she was never able to look after whilst still alive.

The original identity theft is only made possible by this fracturing of traditional communities in favour of impersonal city life. Nobody really knows anybody anymore – Seon-young had claimed to have no family and no close friends so there was no one to vouch for her. Many other young women are in similar positions, orphaned and unmarried, living in urban isolation with only work colleagues to wonder where they’ve got to should they not arrive at the office one day. Loneliness and boredom leave the door wide open for opportunists seeking to exploit such weaknesses for their own various gains.

Byun hints that something is wrong right away by switching to anxious, canted and strange angles filled with oddly cramped compositions. The eerie score enhances the feeling of impending doom as Mun-ho continues to dig into Seong-young’s past, finding confusion and reversals each way he looks. Seong-young was not who she claimed to be, and her tragic past traumas can in no way excuse her later conduct, but even if Mun-ho’s faith in her was not justified, there is a kind of pureness in his unwavering love which adds to the ongoing tragedy. Mun-ho fell in love with the woman Seong-young would have been if life had not been so cruel, and perhaps that part of her loved him too, but life is cruel and now it’s too late. An intriguingly plotted, relentlessly tense thriller Helpless will make you question everything you ever thought you knew about your nearest and dearest, but it is worth remembering that there are some questions it is better not to ask.

Reviewed at the 2016 London Korean Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

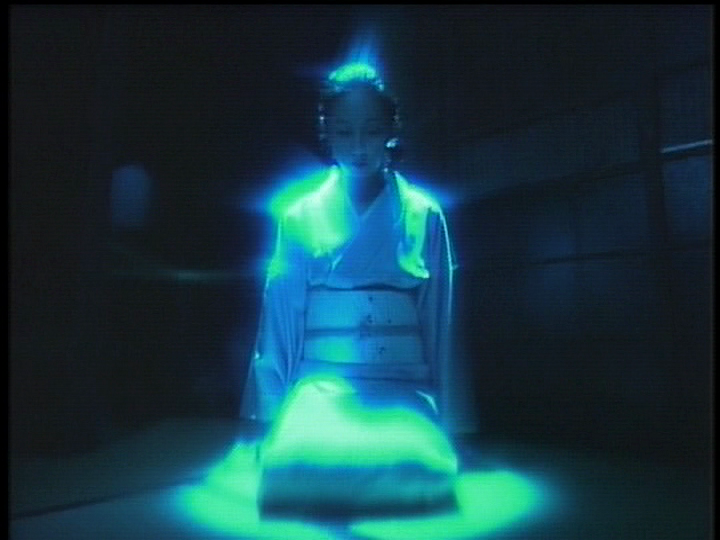

Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.

Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.

One of Japan’s best known actresses with a career spanning over forty years, Kaori Momoi is perhaps just as well known for her outspoken and refreshingly direct approach to interviews as she is for her work with such esteemed directors as Akira Kurosawa, Kon Ichikawa, Yoji Yamada, and Shohei Imamura. One of the few Japanese actors to have made a successful international career starring in Hollywood movies such as Rob Marshall’s Memoirs of a Geisha and international art house fare in Alexander Sukurov’s The Sun, Momoi currently lives in LA and is even reportedly preparing to play Scarlett Johansson’s mother in the upcoming US live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell. It’s perhaps less surprising then that in choosing to adapt a short story by one of Japan’s best young writers, Fuminori Nakamura, Momoi has chosen to shift the story to LA whilst maintaining its Japanese characters.

One of Japan’s best known actresses with a career spanning over forty years, Kaori Momoi is perhaps just as well known for her outspoken and refreshingly direct approach to interviews as she is for her work with such esteemed directors as Akira Kurosawa, Kon Ichikawa, Yoji Yamada, and Shohei Imamura. One of the few Japanese actors to have made a successful international career starring in Hollywood movies such as Rob Marshall’s Memoirs of a Geisha and international art house fare in Alexander Sukurov’s The Sun, Momoi currently lives in LA and is even reportedly preparing to play Scarlett Johansson’s mother in the upcoming US live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell. It’s perhaps less surprising then that in choosing to adapt a short story by one of Japan’s best young writers, Fuminori Nakamura, Momoi has chosen to shift the story to LA whilst maintaining its Japanese characters. The map is not the territory – as the old adage goes. There’s always a difference between the thing itself and the perception of it but, as the “hero” of The Map Against the World (고산자, 대동여지도, Gosanja, Daedongyeojido) points out, if you’re about to set off on a long journey it’s a good idea to not to rely on a linear map else you’ll run out of good shoes long before you reach your destination. Kim Jeong-ho (Cha Seung-Won) was, apparently, a real person (though little is known about him) who set out to make a proper map of the Korean peninsula after a cartographic error led to the death of his father and many other men from his village when they ran out of resources crossing what they thought was one mountain but turned out to be one mountain range.

The map is not the territory – as the old adage goes. There’s always a difference between the thing itself and the perception of it but, as the “hero” of The Map Against the World (고산자, 대동여지도, Gosanja, Daedongyeojido) points out, if you’re about to set off on a long journey it’s a good idea to not to rely on a linear map else you’ll run out of good shoes long before you reach your destination. Kim Jeong-ho (Cha Seung-Won) was, apparently, a real person (though little is known about him) who set out to make a proper map of the Korean peninsula after a cartographic error led to the death of his father and many other men from his village when they ran out of resources crossing what they thought was one mountain but turned out to be one mountain range.

The Fallen Angel (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku), based on one of the best known works of Japanese literary giant Osamu Dazai – No Longer Human, was the last in a series of commemorative film projects marking the 100th anniversary of the author’s birth in 2009. Like much of Dazai’s work, No Longer Human is semi-autobiographical, fixated on the idea of suicide, and charts the course of its protagonist as he becomes hopelessly lost in a life of dissipation, alcohol, drugs, and overwhelming depression.

The Fallen Angel (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku), based on one of the best known works of Japanese literary giant Osamu Dazai – No Longer Human, was the last in a series of commemorative film projects marking the 100th anniversary of the author’s birth in 2009. Like much of Dazai’s work, No Longer Human is semi-autobiographical, fixated on the idea of suicide, and charts the course of its protagonist as he becomes hopelessly lost in a life of dissipation, alcohol, drugs, and overwhelming depression.

How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…

How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…