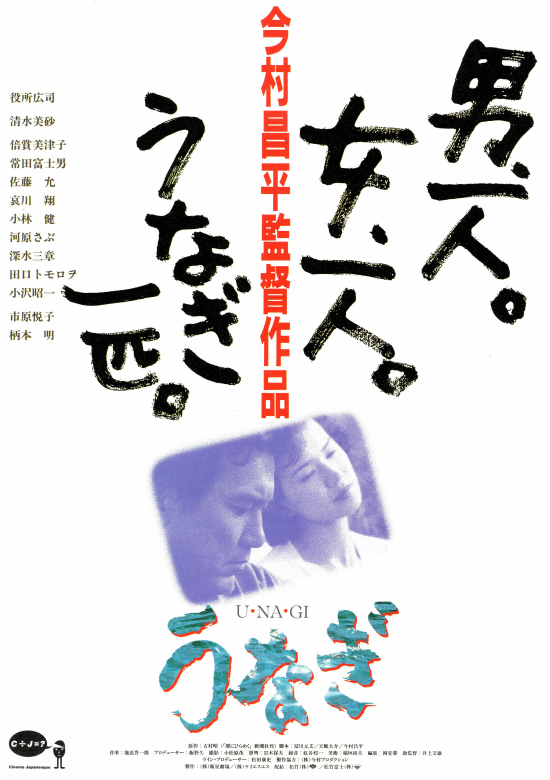

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.

Mild-mannered salary man Yamashita (Kouji Yakusho) receives a handwritten letter filled with beautiful calligraphy delivering the ugly message that his wife has been entertaining another man whilst he enjoys his weekly all night fishing trips. Confused at first, the note begins to work its way into Yamashita’s psyche and so he decides to leave his next fishing trip a little earlier than usual. Peeping through the keyhole, he finds his beloved wife enjoying energetic, passion filled sex with another man. Drawing a knife from a nearby shelf, he enters the room and attacks the pair killing the woman but letting the lover get away.

Yamashita immediately and with perfect calmness turns himself in at the local police station, still covered in his wife’s blood and carrying the murder weapon. Released on a two year probationary period after eight years in jail, there is no one to meet Yamashita when he comes out and so he remains under the guardianship of a Buddhist priest in a nearby town. Accompanied by his only friend, a pet eel, Yamashita takes possession of a local disused barbershop and sets about trying to rebuild his life.

Things change when Yamashita comes across an unconscious woman lying in the grass while he’s out looking for things to feed his eel. The strange thing is, this woman looks exactly like his wife. Eventually, Keiko (Misa Shimizu) recovers and comes to work with Yamashita in his new enterprise but as the pair grow closer the spectres of both of their troubled pasts begin to intrude.

As the small town residents of Yamashita’s new home often remark, Yamashita is a strange man. His deepest relationship is with his eel which the prison guards, who seem quite well disposed towards him, allowed him to keep in the prison pond even though pets are not generally allowed. When asked why he likes his eel so much, Yamshita replies that the eel listens to him and doesn’t tell him the things he does not wish to hear. Like Yamashita, the eel is isolated inside his tank, content to absent himself from interacting with other creatures, both protected and constrained by transparent walls.

After his release from prison, Yamashita begins to reflect on his crime which he doesn’t so much regret but has no desire to repeat. His other double arrives in the form of fellow inmate and double murderer Tamasaki (Akira Emoto) who keeps trying to convince Yamashita that he is living dishonestly by not having visited his wife’s grave or read sutras for her. Though Yamashita pays no heed to most of his advice which is more self-pity and anger than any real concern for Yamashita’s soul, some things begin to get to him, most notably that perhaps the fateful letter never existed at all and is nothing more than the manifestation of Yamashita’s jealous rage.

Though the film presents everything that happens to Yamashita as “real”, his state of mind is continually uncertain. Not only is the provenance of the letter doubted, he doubts the existence of Keiko because she looks (to him at least) like the returned ghost of the woman he killed, and even the final confrontational arguments with Tamasaki take on an unreal quality, as if Yamashita were arguing with himself rather than another man who also represents his own worst qualities – impulsivity, violence, self doubt and insecurity. The film is so deeply embedded in Yamashita’s subjective viewpoint that almost nothing can be taken at face value.

Yamashita is, in a sense, trapped in a hall of mirrors as his own faults are reflected back at him through the people that he meets. Keiko, rather than being physically murdered by a jealous lover, attempted to take her own life after being misused by a faithless (married) man. Her past troubles are, in some ways, the inverse of Yamashita’s as she finds herself at the mercy of dark forces but internalises rather than externalises her own anger. Cheerful and outgoing, she quickly turns Yamshita’s barbershop into a warm and welcoming place which the local community takes to its heart.

Yamashita, however, remains as closed off as ever though he does strike up something of a relationship with a lonely young man who wants to use his barber’s pole to try and call aliens. When Yamashita asks him what he’s going to do if the aliens actually come, the young man replies that he wants to make friends with them. Yamashita astutely remarks that the young man’s desire to meet aliens is down to a failure to connect with people from his own planet – an idea which the young man equally fairly throws back at him. Perhaps out of fear rather than atonement, Yamashita exiles himself from the world at large though gradually through continued exposure to the genial townsfolk and Keiko’s deep seated faith in him, he does begin to swim towards the surface.

Imamura adopts his usual, slightly ironic tone to lighten this otherwise heavy tale allowing the occasional comic set piece to shine through. Yakusho delivers another characteristically nuanced performance as this entirely unformed man, unsure of reality and trapped in a spiral of self doubt and confusion. His original crime of passion is at once chilling in its calmness but also messy and violent as he gives in to animalistic rage. After showing us a street lamp glowing an ominous red, Imamura steeps us in blood as his camera becomes progressively more stained making it impossible to forget the shocking betrayal of this unexpected violence.

Yamashita remarks at one point that he died that day alongside his wife. The Eel is a story of rebirth as its protagonists begin to swim towards the shore in support of each other, though like the titular marine creature there is no guarantee that they will make there alive. Yamashita is a cold blooded murderer and creature of suppressed rage yet Imamura is not interested in moral judgements as much as he is in the messier sides of human nature. A chance offering of redemption for the unredeemable, The Eel offers hope for the hopeless in a world filled with goodhearted eccentrics where all faults are forgivable once they are understood.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

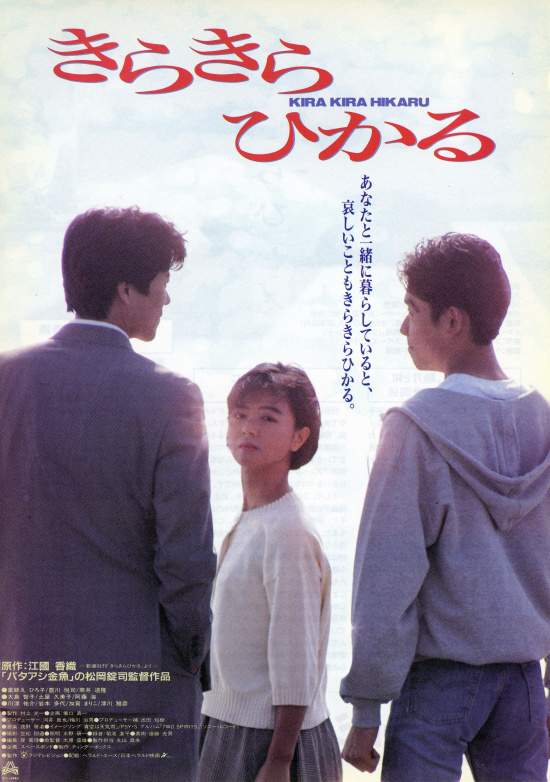

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy. The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as

The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as  If you thought idol movies were all cute and quirky stories of eccentric high school girls with pretty, poppy voices then think again because Memories of You is coming for you and your faith in idols to make everything better. Directed by

If you thought idol movies were all cute and quirky stories of eccentric high school girls with pretty, poppy voices then think again because Memories of You is coming for you and your faith in idols to make everything better. Directed by

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence.

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence. Often, people will try to convince of the merits of something or other by considerably over compensating for its faults. Therefore when you see a movie marketed as the X-ian version of X, starring just about everyone and with a budget bigger than the GDP of a small nation you should learn to be wary rather than impressed. If you’ve followed this very sage advice, you will fare better than this reviewer and not find yourself parked in front of a cinema screen for two hours of non-sensical European fantasy influenced epic adventure such as is League of Gods (3D封神榜, 3D Fēng Shén Bǎng).

Often, people will try to convince of the merits of something or other by considerably over compensating for its faults. Therefore when you see a movie marketed as the X-ian version of X, starring just about everyone and with a budget bigger than the GDP of a small nation you should learn to be wary rather than impressed. If you’ve followed this very sage advice, you will fare better than this reviewer and not find yourself parked in front of a cinema screen for two hours of non-sensical European fantasy influenced epic adventure such as is League of Gods (3D封神榜, 3D Fēng Shén Bǎng). Yoshitmitsu Morita tackled many different genres during his extremely varied career taking in everything from absurd social satire to teen idol vehicles and high art films. 1997’s Lost Paradise (失楽園, Shitsurakuen) again finds him in the art house realm as he prepares a tastefully erotic exploration of middle aged amour fou. Based on the bestselling novel by Junichi Watanabe, Lost Paradise also became a breakout box office hit as audiences were drawn by the tragic tale of doomed late love frustrated by societal expectations.

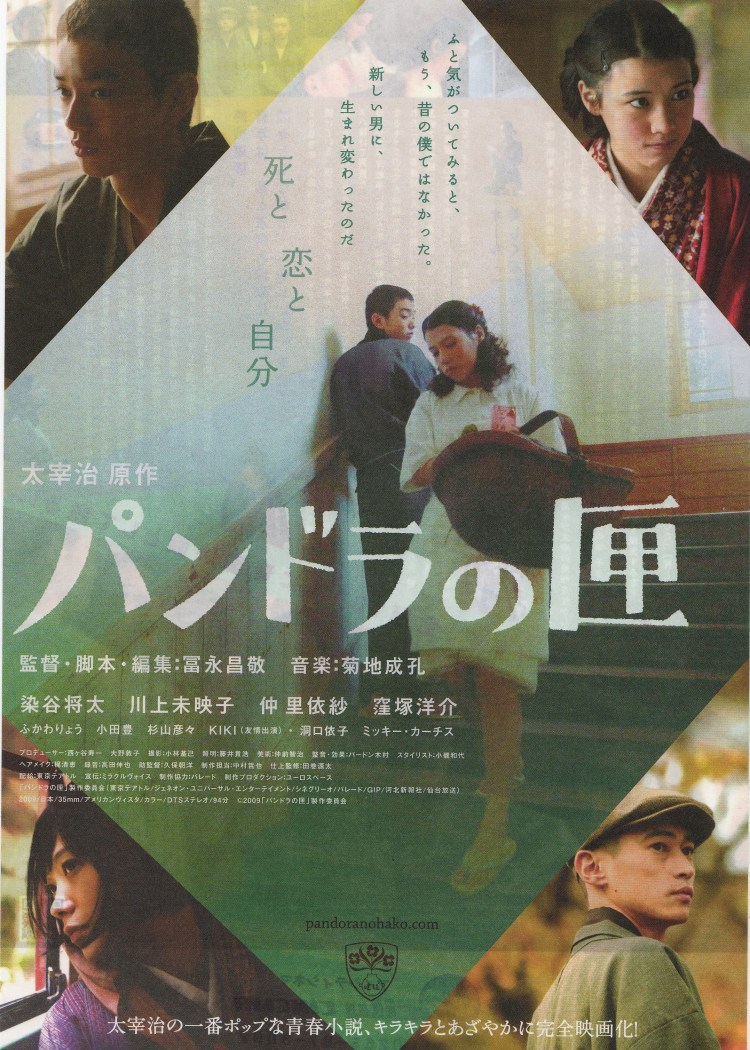

Yoshitmitsu Morita tackled many different genres during his extremely varied career taking in everything from absurd social satire to teen idol vehicles and high art films. 1997’s Lost Paradise (失楽園, Shitsurakuen) again finds him in the art house realm as he prepares a tastefully erotic exploration of middle aged amour fou. Based on the bestselling novel by Junichi Watanabe, Lost Paradise also became a breakout box office hit as audiences were drawn by the tragic tale of doomed late love frustrated by societal expectations. Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic

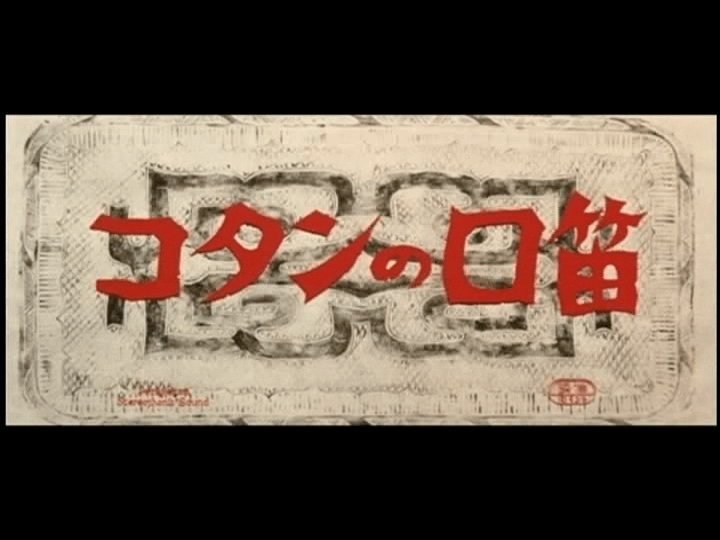

Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic  The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.