It’s a strange thing to say, but no two people can ever know the same person in the same way. We’re all, in a sense, in between each other, only holding some of the pieces in the puzzle of other people’s lives. Lee Dong-eun’s debut feature, In Between Seasons (환절기, Hwanjeolgi), is the story of three people who love each other deeply but find that love tested by secrets, resentments, cultural taboos and a kind of unwilling selfishness.

It’s a strange thing to say, but no two people can ever know the same person in the same way. We’re all, in a sense, in between each other, only holding some of the pieces in the puzzle of other people’s lives. Lee Dong-eun’s debut feature, In Between Seasons (환절기, Hwanjeolgi), is the story of three people who love each other deeply but find that love tested by secrets, resentments, cultural taboos and a kind of unwilling selfishness.

Beginning at the mid-point with a violent car crash, Lee then flashes back four years perviously as Soo-hyun (Ji Yun-ho) introduces his new friend, Yong-joon (Lee Won-gun), to his mother, Mi-keyong (Bae Jong-ok). Soo-hyun’s father has been living abroad in the Philippines for some time and so it’s just the two of them, while Yong-joon’s uneasy sadness is easily explained away on learning that his mother recently committed suicide. Thankful that her son has finally made a friend and feeling sorry for Yong-joon, Mi-kyeong practically adopts him, welcoming him into their home where he becomes a more or less permanent fixture until the boys leave high school.

Four years later, Soo-hyun and Yong-joon are both involved in the car crash which opened the film. Yong-joon has only minor injuries, but Soo-hyun is in a deep coma with possibly irreversible brain damage. It’s at this point that Mi-kyeong finally realises the true nature of the relationship between her son and his friend – that they had been close, inseparable lovers, and that she had never known about it.

When Mi-kyeong receives the phone call to tell her that her son has been in an accident, her friends are joking about their own terrible boys. As one puts it, there are three things a son should never tell his mother – the first being that he’s going to become a monk, the second that he’s going to buy a motorcycle, and the third is something so terrible they can’t even say it out loud. Mi-kyeong’s reaction to discovering her son is gay is predictably negative. Despite having cared for Yong-joon as a mother all these years, she can no longer bear to look at him and tells him on no uncertain terms not come visiting again. Yet for all that her reaction is only half informed by prevailing cultural norms, it’s not so much shame or disgust that she feels as resentment. Here is a man who loves her son, only differently than she does, and therefore knows things about him she never will or could hope to. She is forced to realise that the image she had of Soo-hyun is largely self created and the realisation leaves her feeling betrayed, let down, and rejected.

Both Mi-kyeong and Yong-joon ask the question “What have I done wrong?” at several points in the film – Yong-joon most notably when he’s rejected by Mi-kyeong without explanation, and Mi-kyeong when she’s considering why she’s not been included in the wedding plans for a friend’s daughter. Both Mi-kyeong and Yong-joon are made to feel excluded because they make people “uncomfortable” – Yong-joon because of his sexuality (which he continues to keep secret from his colleagues at work), and Mi-kyeong because of her grief-stricken purgatory. No one quite knows what to say to her, or wants to think about the pain and suffering she must be experiencing. They may claim they don’t want to upset her with something as joyous as a wedding but really it’s more that they don’t want her sadness to cast a shadow over the occasion.

Gradually the ice begins to thaw as Mi-kyeong allows Yong-joon back into her life again even if she can’t quite come to terms with his feelings for her son, describing him as a “friend” and embarrassed by his presence in front of her sister and other visitors. Soo-hyun’s illness and subsequent dependency ironically enough push Mi-kyeong towards the kind of independence she had always rejected – finally learning to drive, sorting out her difficult marital circumstances, and starting to live for herself as well as for her son. Yong-joon remains stubborn and in love, refusing to be shut out of Soo-hyun’s life even whilst considering the best way to live his own. Beautifully composed in all senses of the word, Lee’s frames are filled with anxious longing and inexpressible sadness tempered with occasional joy. Too astute to opt for a crowd pleasing victory, Lee ends on a more realistic note of hopeful ambiguity with anxiety seemingly exorcised and replaced with tranquil, easy sleep.

Screened at the London Korean Film Festival 2017. In Between Seasons will also be screened at the Broadway Cinema in Nottingham on 11th November.

Trailer/behind the scenes EPK (no subtitles)

Interview with director Lee Dong-eun conducted during the film’s screening at the Busan International Film Festival in 2016.

Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

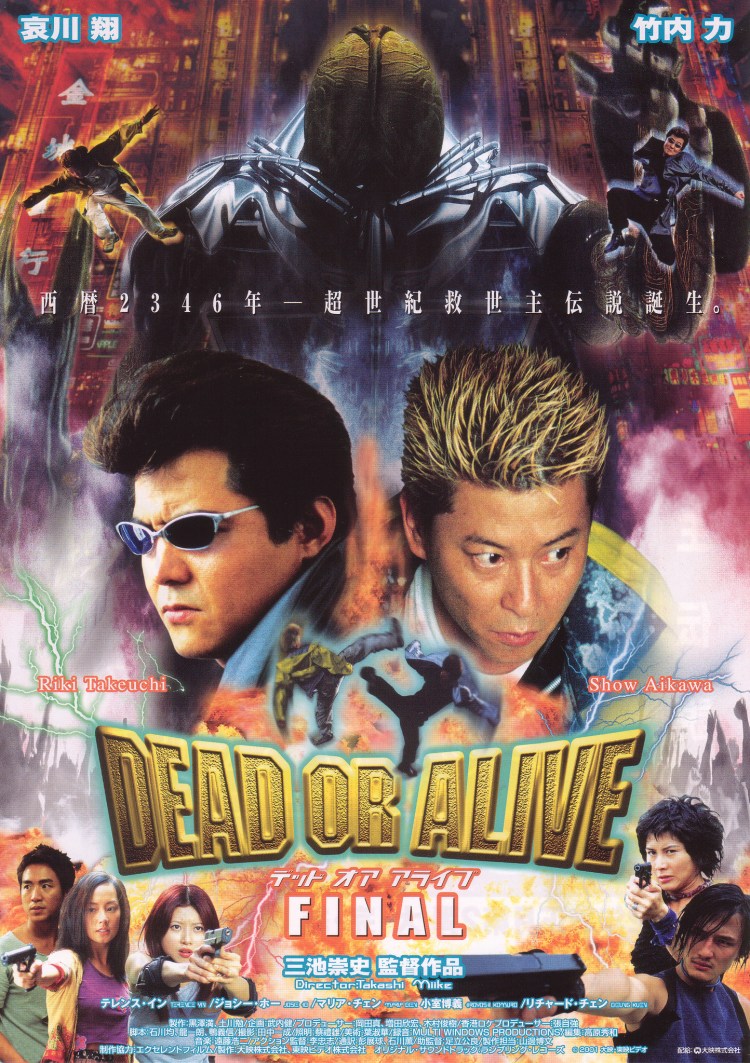

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of  In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support.

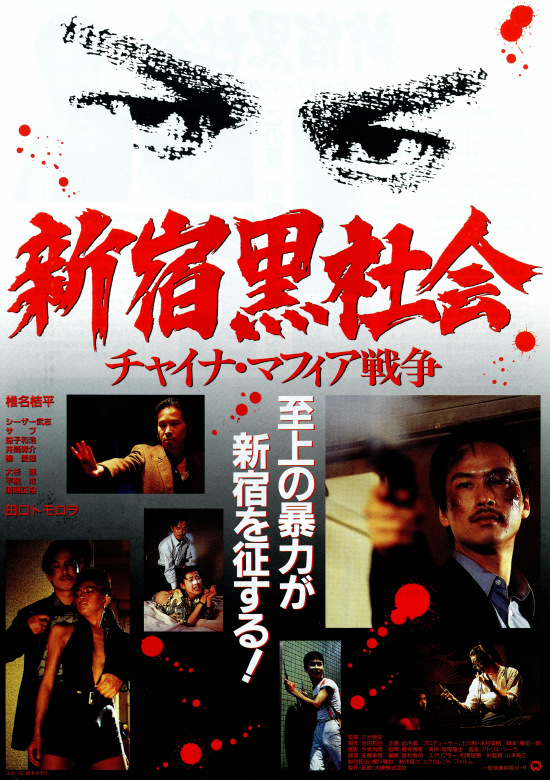

In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support. The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as

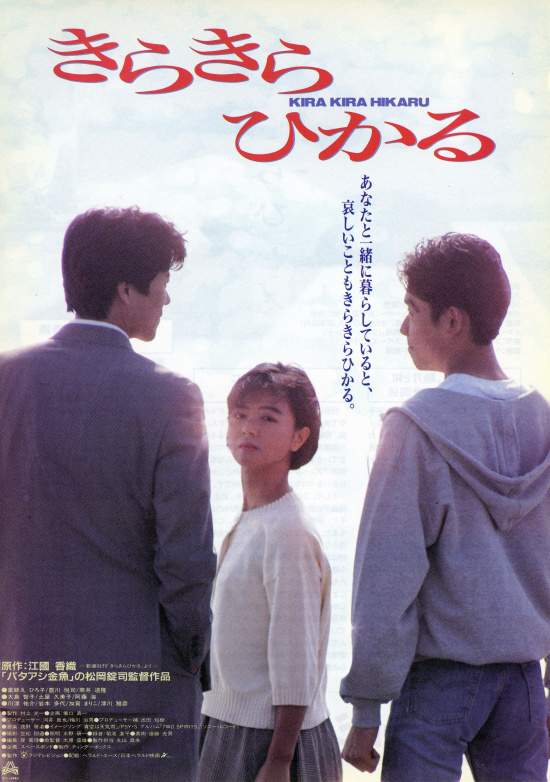

The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as  The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics. Yusaku Matsuda may have been the coolest action star of the ‘70s but by the end of the decade he was getting bored with his tough guy persona and looked to diversify his range a little further than his recent vehicles had allowed him. Matsuda had already embarked on a singing career some years before but in Eiichi Kudo’s Yokohama BJ Blues (ヨコハマBJブルース), he was finally allowed to display some of his musical talents on screen as a blues singer and ex-cop who makes ends meet through his work as a detective for hire.

Yusaku Matsuda may have been the coolest action star of the ‘70s but by the end of the decade he was getting bored with his tough guy persona and looked to diversify his range a little further than his recent vehicles had allowed him. Matsuda had already embarked on a singing career some years before but in Eiichi Kudo’s Yokohama BJ Blues (ヨコハマBJブルース), he was finally allowed to display some of his musical talents on screen as a blues singer and ex-cop who makes ends meet through his work as a detective for hire.