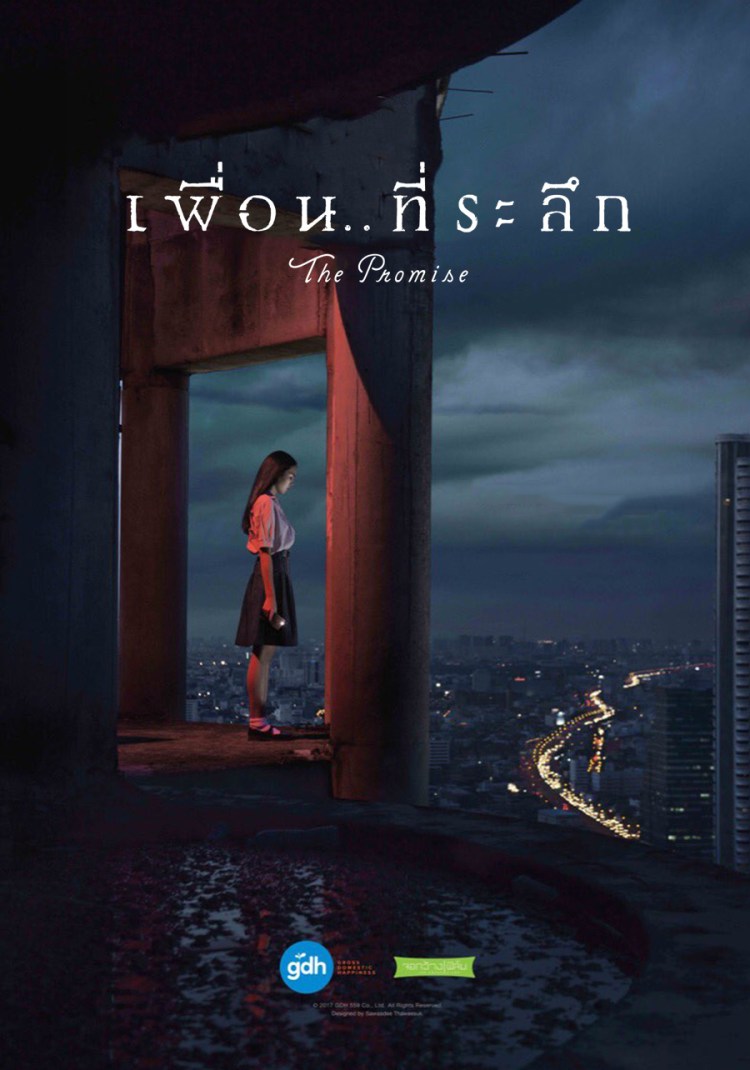

20 years on the Asian financial crisis continues to loom large over the region’s cinema, providing fertile ground for extreme acts of transgression born of desperation in the wake of such a speedy decline. Sophon Sakdaphisit’s ghost story The Promise (เพื่อน..ที่ระลึก, Puen Tee Raluek) places the financial crisis at its centre in its cyclical tales of betrayed youth who find themselves paying heavily for their parents’ mistakes through no fault of their own. Yet there is a fault involved in the betraying of a sacred promise between two vulnerable young people made half in jest in a fit of pique but provoking tragic consequences all the same. Sometimes lonely death chases the young too, trapping them in solitary limbo growing ever more resentful of their heinous betrayal.

20 years on the Asian financial crisis continues to loom large over the region’s cinema, providing fertile ground for extreme acts of transgression born of desperation in the wake of such a speedy decline. Sophon Sakdaphisit’s ghost story The Promise (เพื่อน..ที่ระลึก, Puen Tee Raluek) places the financial crisis at its centre in its cyclical tales of betrayed youth who find themselves paying heavily for their parents’ mistakes through no fault of their own. Yet there is a fault involved in the betraying of a sacred promise between two vulnerable young people made half in jest in a fit of pique but provoking tragic consequences all the same. Sometimes lonely death chases the young too, trapping them in solitary limbo growing ever more resentful of their heinous betrayal.

In 1997, Ib (Panisara Rikulsurakan) and Boum (Thunyaphat Pattarateerachaicharoen) are best friends. Daughters of wealthy industrialists making an ill fated move into real estate with the building of a luxury tower block destined never to be completed, Boum and Ib may have been separated by being sent to different schools, but they spend all of their free time together, often hiding out on the construction site fantasising about sharing an apartment there and listening to sad songs on Ib’s ever present Discman.

When the crisis hits and their fathers are ruined, the girls pay the price. Not only are they left feeling betrayed and humiliated in being so abruptly ejected from their privileged world of mansions and horse riding, but also suffer at the hands of the fathers they now despite – Ib more literally as she is physically beaten by her strung out, frustrated dad. Already depressed, Ib talks ominously about a gun her mother has hidden in fear her father may use it to kill himself. When Boum falls out with her mum, she gives the go ahead for a double suicide but can’t go through with it after watching the twitching body of her friend, lying in a pool of blood after firing a bullet up through her chin.

20 years later, Boum (Numthip Jongrachatawiboon) is a successful industrialist herself, apparently having taken over her father’s company and turned it around. The economy is, however, once again in a precarious position and Boum’s business is floundering thanks to a set back on a high profile project. The idea is floated to finish the tower left incomplete by the ’97 crisis to which Boum reluctantly agrees. Meanwhile, Boum’s daughter Bell (Apichaya Thongkham) is about to turn 15 – the same age as she was when she agreed to die with Ib, and has recently started sleepwalking in ominous fashion.

Sophon Sakdaphisit neatly compares and contrasts the teenagers of 20 years ago and those of today and finds them not altogether different. In 1997, Boum and Ib keep in touch with pagers and visit photo sticker booths in the mall, splitting earphones to listen to a Discman while they take solitary refuge at the top of a half completed tower. In 2017, Bell never sees her friend in person but keeps in touch via video messaging, posting photos on instagram, and sending each other songs over instant messenger. Yet Bell, in an ominous touch, still graffitis walls to make her presence felt just as her mother had done even if she fetishises the retro tech of her mother’s youth, picking up an abandoned pager just because it looks “cool”.

In 2017, the now widowed Boum appears to have no close friends though her relationship with her daughter is tight and loving. A “modern” woman, Boum dismisses the idea that a malevolent spirit could be behind her daughter’s increasingly strange behaviour but finds it hard to argue with the CCTV footage which seems almost filled with the invisible presence of something dark and angry. Realising that the circumstances have converged to bring her teenage trauma back to haunt her – Ib’s suicide, the tower, her daughter’s impending birthday, Boum is terrified that Ib has come back to claim what she was promised and plans to take her daughter in her place in revenge for her betrayal all those years ago.

Bell is made to pay the price for her mother’s mistakes, as she and Ib were made to pay for their fathers’. Motivated by intense maternal love, Boum nevertheless is quick to bring other people’s children into the chain of suffering when she forces a terrified little boy who has the ability to see ghosts to help her locate the frightening vision of her late friend as she darts all over the dank and spooky tower block, threatening the financial security of his family all of whom work for her company and are dependent on her for their livelihoods.

In order to move forward, Boum needs to address her longstanding feelings of guilt regarding her broken promise – the suicide was, after all, her idea even if she was never really serious and after witnessing her friend die in such a violent way, she simply ran away and left her there all alone and bleeding. Yet rather than attempting to keep her original promise Boum makes a new one with her imperilled daughter – that she will keep on living, no matter what. The slightly clumsy message being that commitment to forward motion is the only way to leave the past behind, accepting your feelings of guilt and regret but learning to let them go and the ghosts dissipate. Sophon Sakdaphisit makes use of the notorious, believed haunted Bangkok tower to create an eerie, supernaturally charged atmosphere of malevolence but the ghosts are in a sense very real, recalling the turbulence of two decades past in which fear and hysteria ruled and young lives were cut short by a nihilistic despair that even friendship could not ease.

Screened at the 20th Udine Far East Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Finding the sinister in the commonplace is the key to creating a chilling horror experience, but “finding” it is the key. Attempting to graft something untoward onto a place it can’t take hold is more likely to raise eyebrows than hair or goosebumps. The creators of Korean horror exercise Manhole (맨홀) have decided to make those ubiquitous round discs the subject of their enquiries. They are kind of worrying really aren’t they? Where do they go, what are they for? Only the municipal authorities really know. In this case they go to the lair of a weird serial killer who lives in the shadows and occasionally pulls in pretty girls from above like one of those itazura bank cats after your loose change.

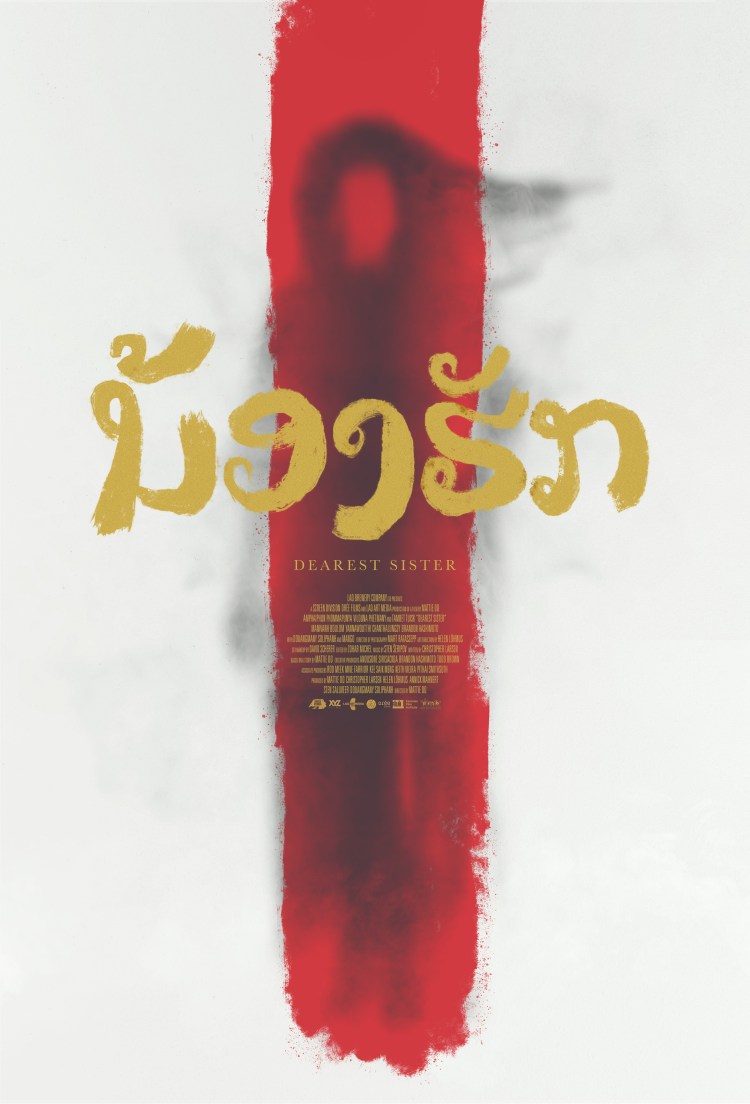

Finding the sinister in the commonplace is the key to creating a chilling horror experience, but “finding” it is the key. Attempting to graft something untoward onto a place it can’t take hold is more likely to raise eyebrows than hair or goosebumps. The creators of Korean horror exercise Manhole (맨홀) have decided to make those ubiquitous round discs the subject of their enquiries. They are kind of worrying really aren’t they? Where do they go, what are they for? Only the municipal authorities really know. In this case they go to the lair of a weird serial killer who lives in the shadows and occasionally pulls in pretty girls from above like one of those itazura bank cats after your loose change. Marxist countries and horror movies often do not mix. Laos has only a fledgling cinema industry and Mattie Do, returning with her second film Dearest Sister (ນ້ອງຮັກ, Nong hak), is its only female filmmaker even if she finds herself a member of an extremely small group. Set in Laos it may be, but Dearest Sister also has something of the European gothic in its instantly recognisable tale of a good country girl fetching up in the city only to be treated like a poor relation and eventually corrupted by its dubious charms. Dearest Sister is a horror movie but one which places very real fears, albeit ones imbued with superstition, at the forefront of its tragedy.

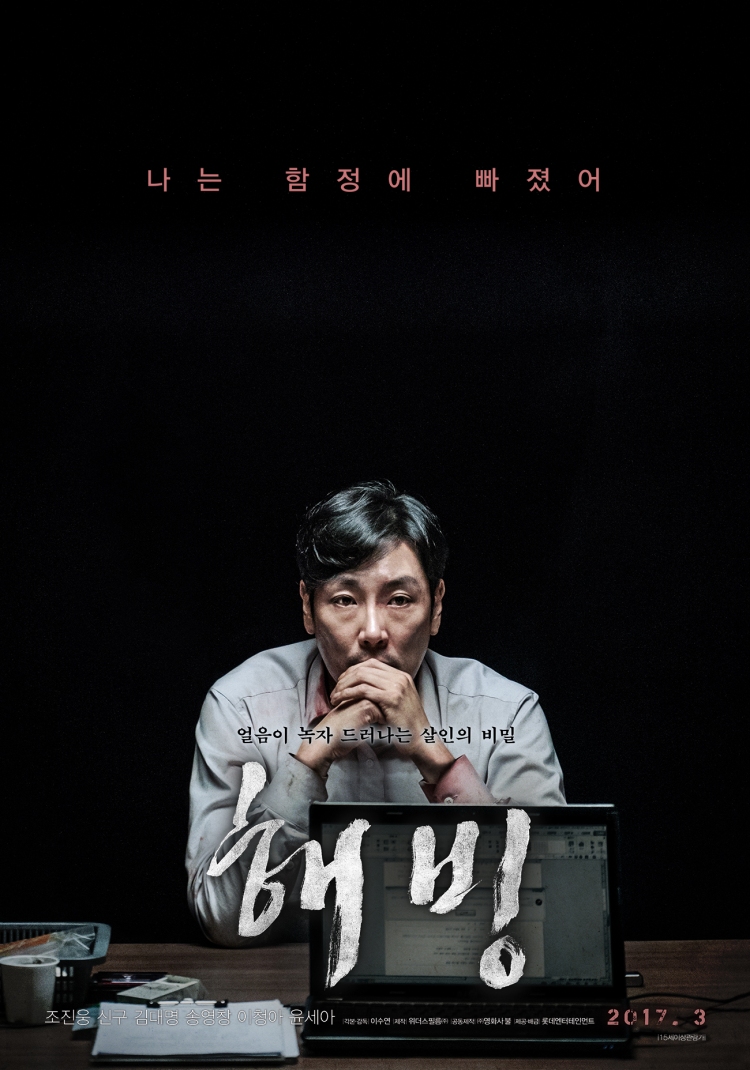

Marxist countries and horror movies often do not mix. Laos has only a fledgling cinema industry and Mattie Do, returning with her second film Dearest Sister (ນ້ອງຮັກ, Nong hak), is its only female filmmaker even if she finds herself a member of an extremely small group. Set in Laos it may be, but Dearest Sister also has something of the European gothic in its instantly recognisable tale of a good country girl fetching up in the city only to be treated like a poor relation and eventually corrupted by its dubious charms. Dearest Sister is a horror movie but one which places very real fears, albeit ones imbued with superstition, at the forefront of its tragedy. If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects.

If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects. Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from

Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from  No ghosts! That’s one of the big rules when it comes to the Chinese censors, but then these “ghosts” are not quite what they seem and belong to the pre-communist era when the people were far less enlightened than they are now. One of the few directors brave enough to tackle horror in China, Raymond Yip Wai-man goes for the gothic in this Phantom of the Opera inspired tale of love and the supernatural set in bohemian ‘30s Shanghai, Phantom of the Theatre (魔宫魅影, Mó Gōng Mèi Yǐng). As expected, the thrills and chills remain mild as the ghostly threat edges closer to its true role as metaphor in a revenge tale that is in perfect keeping with the melodrama inherent in the genre, but the full force of its tragic inevitability gets lost in the miasma of awkward CGI and theatrical artifice.

No ghosts! That’s one of the big rules when it comes to the Chinese censors, but then these “ghosts” are not quite what they seem and belong to the pre-communist era when the people were far less enlightened than they are now. One of the few directors brave enough to tackle horror in China, Raymond Yip Wai-man goes for the gothic in this Phantom of the Opera inspired tale of love and the supernatural set in bohemian ‘30s Shanghai, Phantom of the Theatre (魔宫魅影, Mó Gōng Mèi Yǐng). As expected, the thrills and chills remain mild as the ghostly threat edges closer to its true role as metaphor in a revenge tale that is in perfect keeping with the melodrama inherent in the genre, but the full force of its tragic inevitability gets lost in the miasma of awkward CGI and theatrical artifice. Walk a mile in a man’s shoes, they say, if you really want to understand him. If Kim Yong-gyun’s The Red Shoes (분홍신, Bunhongsin, 2005) is anything to go by, you’d better make sure you ask first and return them to their rightful owner afterwards without fear or covetousness. Loosely based on the classic Hans Christian Andersen tale this Korean take replaces dancing with murder and also mixes in elements from other popular Asian horror movies of the day, most notably

Walk a mile in a man’s shoes, they say, if you really want to understand him. If Kim Yong-gyun’s The Red Shoes (분홍신, Bunhongsin, 2005) is anything to go by, you’d better make sure you ask first and return them to their rightful owner afterwards without fear or covetousness. Loosely based on the classic Hans Christian Andersen tale this Korean take replaces dancing with murder and also mixes in elements from other popular Asian horror movies of the day, most notably