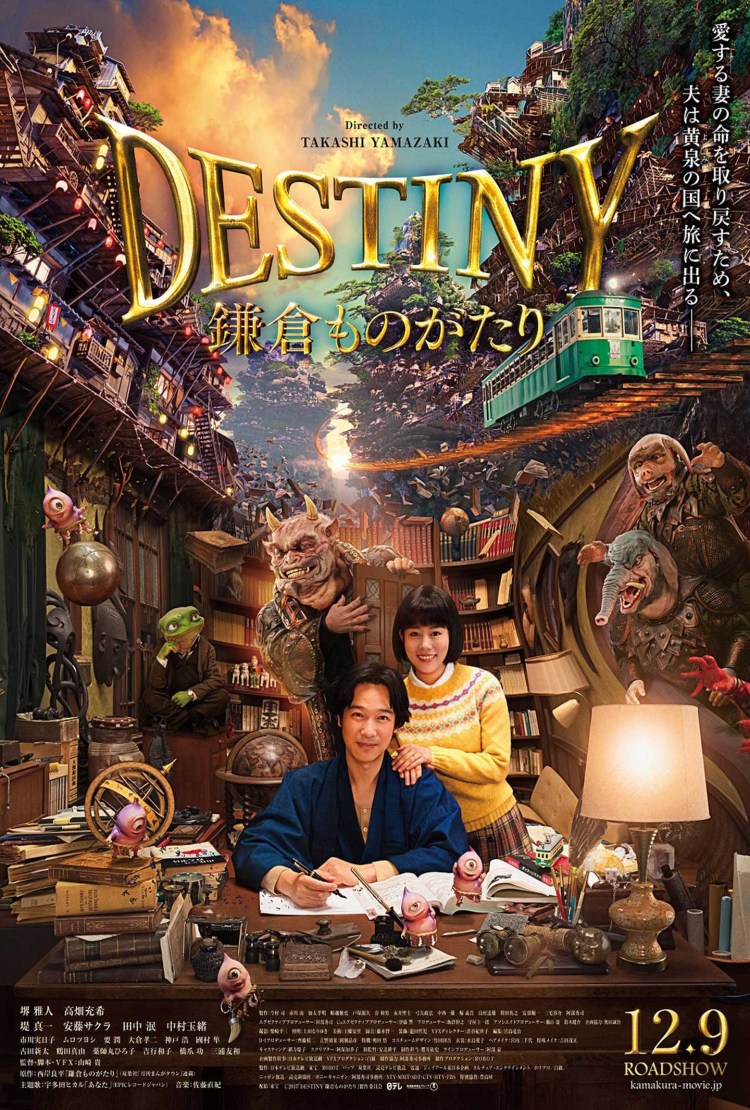

Japanese literature has its fair share of eccentric detectives and sometimes they even end up as romantic heroes, only to have seemingly forgotten the current love interest by the time the next case rolls around. This is very much not true of Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura (DESTINY 鎌倉ものがたり, Destiny: Kamakura Monogatari) which is an exciting adventure featuring true love, supernatural creatures, and a visit to the afterlife all spinning around a central crime mystery. Blockbuster master Takashi Yamazaki brings his visual expertise to the fore in adapting the popular ‘80s manga by Ryohei Saigan in which the human and supernatural worlds overlap in the quaint little town of Kamakura which itself seems to exist somewhere out of time.

Japanese literature has its fair share of eccentric detectives and sometimes they even end up as romantic heroes, only to have seemingly forgotten the current love interest by the time the next case rolls around. This is very much not true of Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura (DESTINY 鎌倉ものがたり, Destiny: Kamakura Monogatari) which is an exciting adventure featuring true love, supernatural creatures, and a visit to the afterlife all spinning around a central crime mystery. Blockbuster master Takashi Yamazaki brings his visual expertise to the fore in adapting the popular ‘80s manga by Ryohei Saigan in which the human and supernatural worlds overlap in the quaint little town of Kamakura which itself seems to exist somewhere out of time.

Our hero, Masakazu Isshiki (Masato Sakai), is a best selling author, occasional consulting detective, and befuddled newlywed. He’s just returned from honeymoon with his lovely new wife and former editorial assistant, Akiko (Mitsuki Takahata), but there are a few things he’s neglected to explain to her about her new home. To wit, Kamakura is a place where humans, supernatural creatures, and wandering spirits all mingle freely though those not familiar with the place may assume the tales to be mere legends. To her credit, Akiko is a warm and welcoming person who can’t help being “surprised” by the strange creatures she begins to encounter but does her best to get used to their presence and learn about the ancient culture of the town in which she intends to spend her life. Unfortunately, she still has a lot to learn and an “incident” with a strange mushroom and a naughty monster eventually leads to her soul being accidentally sent off to the afterworld by a very sympathetic death god (Sakura Ando) who is equal parts apologetic about and confused by what seems to be a bizarre clerical error.

Destiny’s Kamakura is a strange place which seems to exist partly in the past. At least, though you can catch a glimpse of people in more modern clothing in the opening credits, the town itself has a distinctly retro feel with ‘60s decor, old fashioned cars, and rotary phones while Masakazu plays with vintage train sets, pens his manuscripts by hand, and delivers them in an envelope to his editor who knows him well enough to understand that deadlines are both Masakazu’s best friend and worst enemy.

The creatures themselves range from the familiar kappa to more outlandish human-sized creatures conjured with a mix of physical and digital effects and lean towards the intersection of cute and creepy. The usual fairytale rules apply – you must be careful of making “deals” with supernatural creatures and be sure to abide by their rules, only Akiko doesn’t know about their rules and Masakazu hasn’t got round to explaining them which leaves her open to various kinds of supernatural manipulation which he is too absent minded to pick up on.

Yet Masakazu will have to wake himself up a bit if he wants to save his wife from an eternity spent as the otherworld wife of a horrible goblin who, as it turns out, has been trying to split the couple up since the Heian era only they always manage to find each other in every single re-incarnation. True love is a universal law, but it might not be strong enough to fend off mishandled bureaucracy all on its own, which is where Akiko’s naivety and essential goodness re-enter the scene when her unexpected kindness to a bad luck god (Min Tanaka), and an officious death god who knew something was fishy with all these irreconcilable numbers, enable the couple to make a speedy escape and pursue their romantic destiny together.

Aimed squarely at family audiences, the film also delves a little into the awkward start of married life as Akiko tries to get used to her eccentric husband’s irregular lifestyle as well as his childlike propensity to try and avoid uncomfortable topics by running off to play trains. Masakazu, orphaned at a young age, is slightly arrested in post-adolescent emotional immaturity and never expected to get married after discovering something that made him question his parents’ relationship. Nevertheless, a visit to the afterlife will do wonders for making you reconsider your earthly goals and Masakazu is finally able to repair both his old family and his new through a bit of communing with the dead. Charming, heartfelt, and boasting some beautifully designed world building, Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura is the kind of family film you didn’t think they made anymore – genuinely romantic and filled with pure-hearted cheer.

Screened at Nippon Connection 2018.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Conventional wisdom states it’s better not to get involved with the yakuza. According to Hamon: Yakuza Boogie (破門 ふたりのヤクビョーガミ Hamon: Futari no Yakubyogami), the same goes for sleazy film execs who can prove surprisingly slippery when the occasion calls. Based on Hiroyuki Kurokawa’s Naoki Prize winning novel and directed by Shotaro Kobayashi who also adapted the same author’s Gold Rush into a successful WOWWOW TV Series, Hamon: Yakuza Boogie is a classic buddy movie in which a down at heels slacker forms an unlikely, grudging yet mutually dependent relationship with a low-level gangster.

Conventional wisdom states it’s better not to get involved with the yakuza. According to Hamon: Yakuza Boogie (破門 ふたりのヤクビョーガミ Hamon: Futari no Yakubyogami), the same goes for sleazy film execs who can prove surprisingly slippery when the occasion calls. Based on Hiroyuki Kurokawa’s Naoki Prize winning novel and directed by Shotaro Kobayashi who also adapted the same author’s Gold Rush into a successful WOWWOW TV Series, Hamon: Yakuza Boogie is a classic buddy movie in which a down at heels slacker forms an unlikely, grudging yet mutually dependent relationship with a low-level gangster. Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen.

Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen. After such a long and successful career, Yoji Yamada has perhaps earned the right to a little retrospection. Offering a smattering of cinematic throwbacks in homages to both Yasujiro Ozu and Kon Ichikawa, Yamada then turned his attention to the years of militarism and warfare in the tales of a struggling mother,

After such a long and successful career, Yoji Yamada has perhaps earned the right to a little retrospection. Offering a smattering of cinematic throwbacks in homages to both Yasujiro Ozu and Kon Ichikawa, Yamada then turned his attention to the years of militarism and warfare in the tales of a struggling mother,  Coming in at the end of the “pure love” boom, Nobuhiro Doi’s second feature, Tears for You (涙そうそう, Nada So So) is presumably named to tie in with his smash hit debut

Coming in at the end of the “pure love” boom, Nobuhiro Doi’s second feature, Tears for You (涙そうそう, Nada So So) is presumably named to tie in with his smash hit debut

If there is a frequent criticism directed at the always bankable director Yoji Yamada, it’s that his approach is one which continues to value the past over the future. Recent years have seen him looking back, literally, in terms of both themes and style with remakes of films by two Japanese masters – Ozu in his Tokyo Story homage Tokyo Family, and Kon Ichikawa in Her Brother. While he chose to update both of those pieces for the modern day, 2008’s

If there is a frequent criticism directed at the always bankable director Yoji Yamada, it’s that his approach is one which continues to value the past over the future. Recent years have seen him looking back, literally, in terms of both themes and style with remakes of films by two Japanese masters – Ozu in his Tokyo Story homage Tokyo Family, and Kon Ichikawa in Her Brother. While he chose to update both of those pieces for the modern day, 2008’s  Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes.

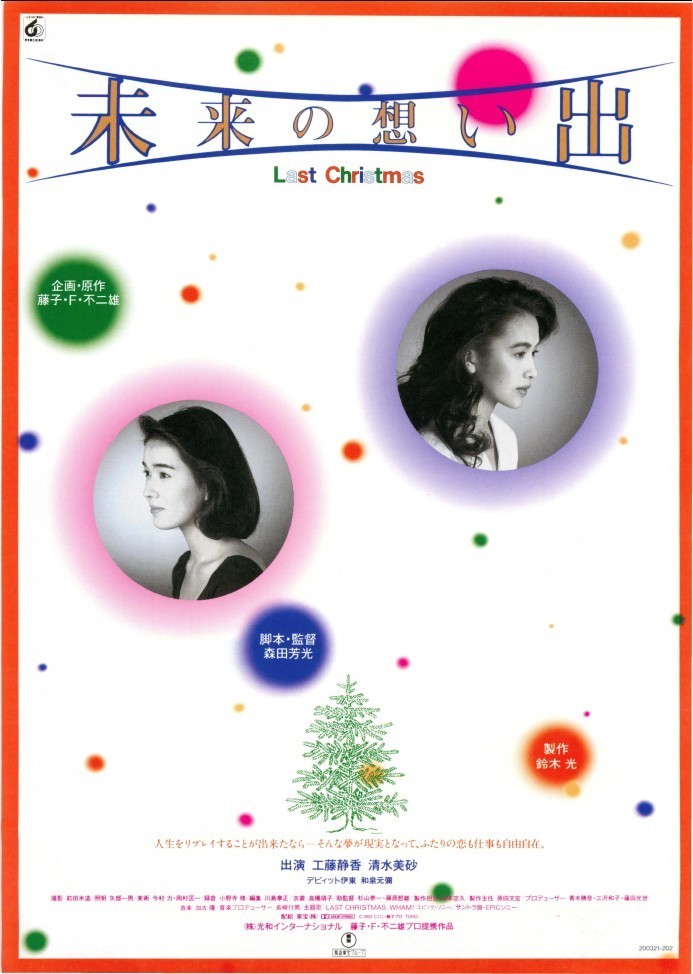

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes. Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.

It’s never too late to be what you might have been – a statement attributed to George Eliot which may be as fake as one of the promises offered by the protagonist of Hirokazu Koreeda’s latest attempt to chart the course of his nation through its basic social unit, After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori mo Mada Fukaku). Reuniting Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe as mother and son following their star turns in

It’s never too late to be what you might have been – a statement attributed to George Eliot which may be as fake as one of the promises offered by the protagonist of Hirokazu Koreeda’s latest attempt to chart the course of his nation through its basic social unit, After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori mo Mada Fukaku). Reuniting Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe as mother and son following their star turns in