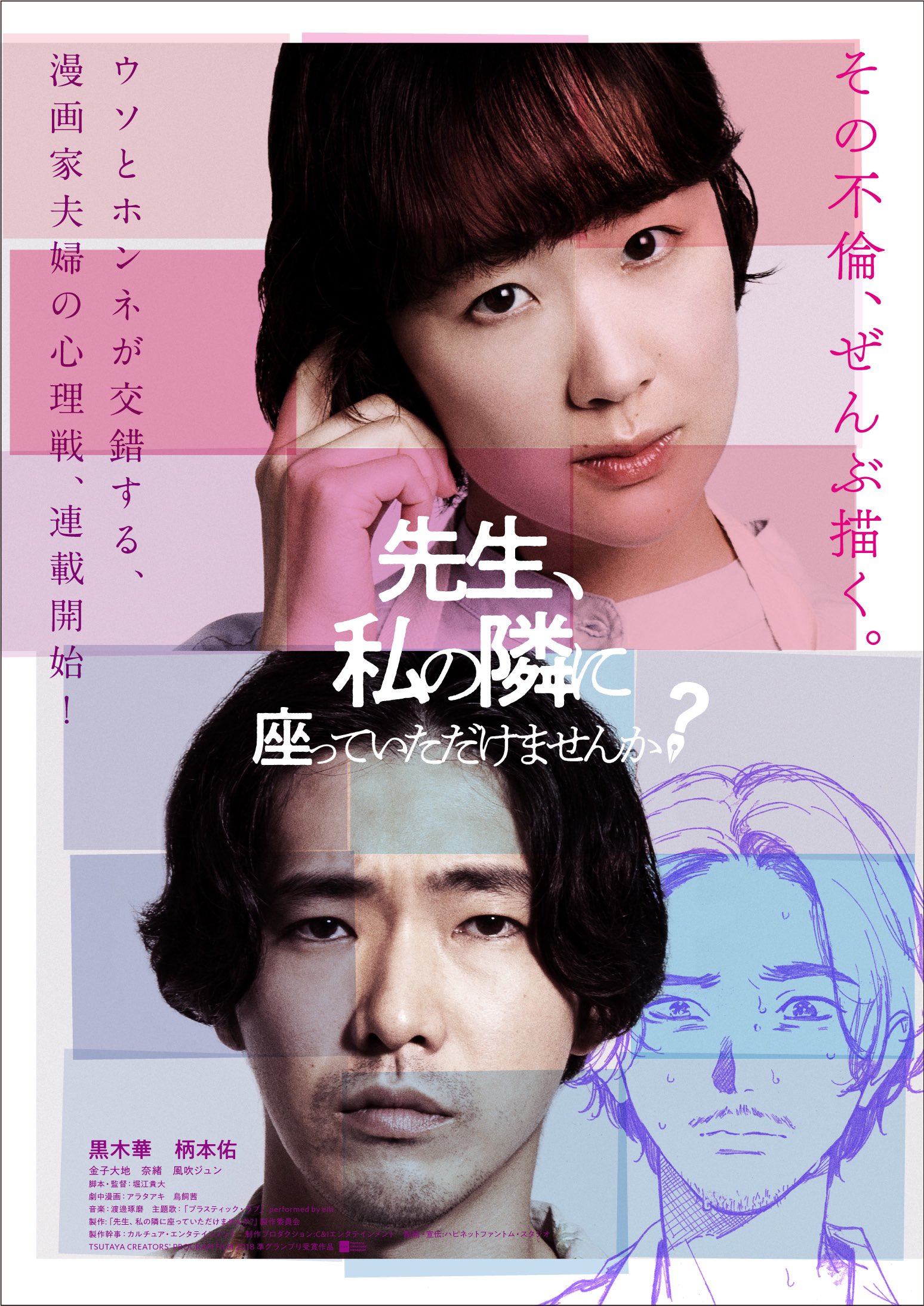

An under-confident mangaka tries to save her moribund marriage through a passive aggressive attempt at “realism”, but then is that really what she wants? What is she really up to? Takahiro Horie’s anti-rom-com Sensei, Would You Sit Beside me? (先生、私の隣に座っていただけませんか?, Sensei, Watashi no Tonari ni Suwatte Itadakemasenka?) is more complicated than it first seems, a tale of romantic revenge, of a woman’s determination to reclaim her independence, or perhaps even a slightly cynical not to mention sexist story of a betrayed wife’s attempts to rekindle her moody husband’s creative mojo in the hope of reigniting the spark in their marriage. What transpires is however a literary game of cat and mouse as a suddenly alarmed husband attempts to get ahead of the game through the transgressive act of reading his wife’s diary.

A successful manga artist, Sawako (Haru Kuroki) has just completed a long-running series assisted by her husband of five years, Toshio (Tasuku Emoto) who was once a bestselling mangaka himself but hasn’t worked on anything of his own since they got married. Toshio appears to be prickly on this subject, and is in something of a bad mood while Sawako’s editor Chika (Nao Honda) waits patiently for the completed pages. Seemingly suspecting something, Sawako asks Toshio to escort Chika back to the station with the intention of following them only she’s interrupted by a phone call from the police to the effect that her mother (Jun Fubuki), who lives out in the country, has been in an accident and broken her ankle. Sawako and Toshio decide to go and stay with her while she recovers, though a change of scene seems to do little to relieve the pressures on their marriage.

Indeed, on their first night there Toshio remarks that it’s been a while since they’ve slept in the same room which might go some way to explaining the distance in their relationship. Aside from that, Toshio superficially seems much more cheerful perhaps putting on a best behaviour act for his mother-in-law who makes a point of telling her daughter how “great” her husband is and how she’s almost glad she broke her leg because it’s brought him to stay. Her gentle hints to Sawako to let her know if there’s something wrong elicit only a characteristic “hmm” while she otherwise makes only passive-aggressive comments which suggest she fears her marriage may be on the way out. Having long been resistant to the idea of learning to drive even though she grew up in the country, Sawako starts taking lessons at a nearby school cryptically explaining to Toshio that perhaps she’d better learn after all because she’ll be stuck when he leaves her.

Sawako’s “driving phobia” as she first describes it appears to be a facet of her underlying lack of self-confidence. She simply doesn’t trust herself to take the wheel and cannot operate without the safety net of someone sitting next to her. Having not got on with the grumpy old man she was originally assigned, Sawako gains the courage to take her foot off the brake thanks to a handsome young instructor, Shintani (Daichi Kaneko), who makes her feel safe while slowly giving her the confidence to trust in herself. The implication is that Toshio has been unable to do something similar in part because he’s so wrapped up in his own inferiority complex over his creative decline complaining that nothing really moves him anymore. When Chika advises Sawako choose a more “realistic” subject for her next series, she passively aggressively decides to go all in with a clearly autobiographical tale of adultery that suggests she is well aware her husband and editor are having an affair behind her back while the heroine experiences a passionate reawakening thanks to her handsome, sensitive driving instructor.

Of course, Toshio can’t resist reading her “diary” and obsessing over how much of it is “true”. Perhaps Sawako intended just this effect, driving her husband out of his mind with guilt and jealousy indulging in a little revenge whether in fantasy or reality. The irony is that there are at least three “senseis” floating around including Sawako herself with the eventual decision of who, if anyone, she wants to sit beside her the unanswered question of her “revenge” manga. Her real revenge, however, may lie in her determination to grab the wheel, reclaiming agency over her life along with a new independence born of her ability to drive and therefore decide its further direction while toying with Toshio’s inner insecurity in order to effect a plan which is far more insidious than it might first seem. Filled with twists and turns, Horie’s cynical love farce eventually cedes total control to its seemingly mousy heroine as she gains the confidence to go solo or hand-in-hand as it suits her towards a destination entirely of her own choosing.

Sensei, Would You Sit Beside Me? screened as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

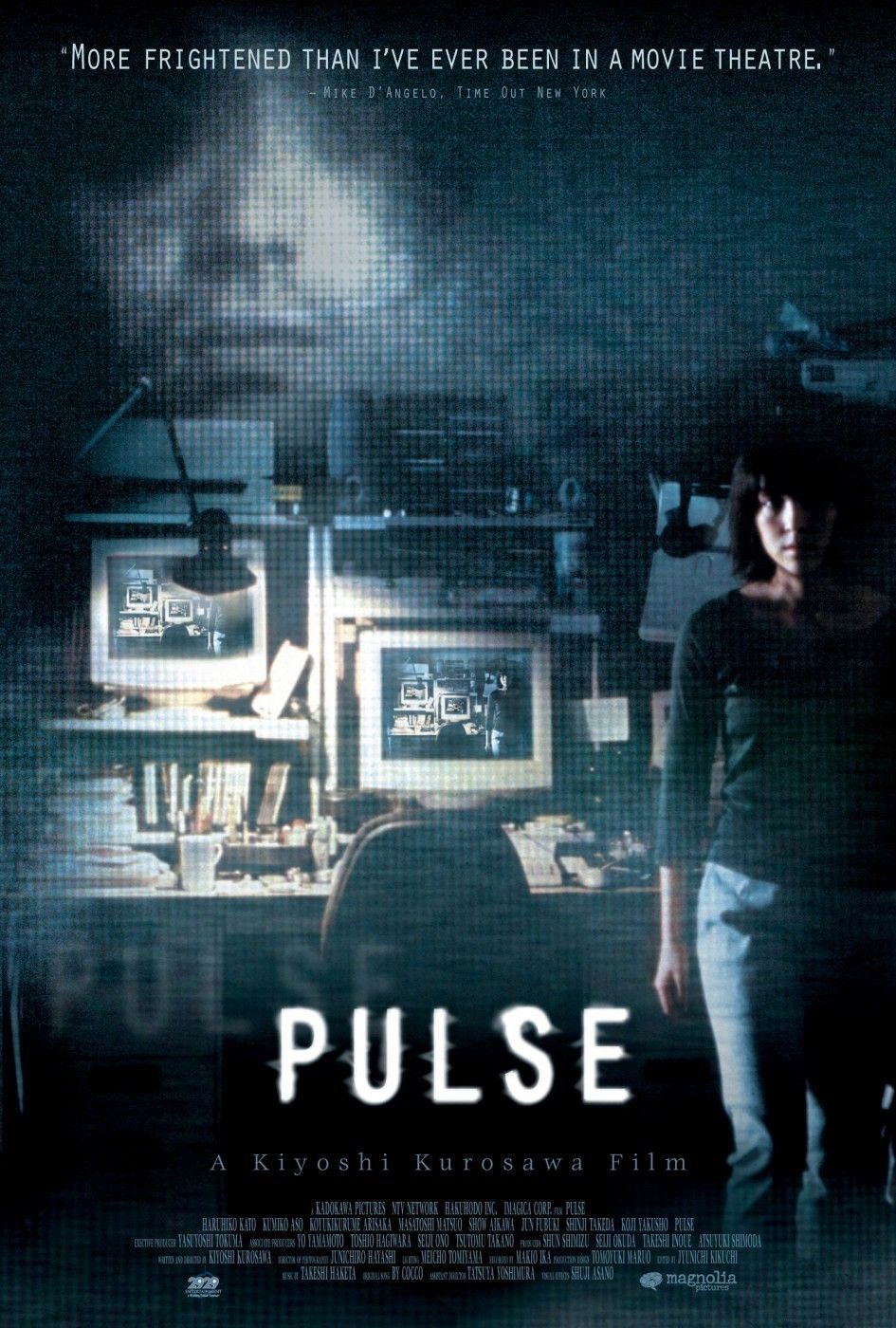

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence.

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence. Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes.

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes. You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals.

You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals. Summer Holiday Everyday – It’s certainly an upbeat way to describe unemployment but then everything is improbably upbeat and cheerful in the always sunny world of Shusuke Kaneko’s adaptation of Yumiko Oshima’s shoujo manga. Published in the mid-bubble era of 1988, Oshima’s world is one in which anything is possible but by the time of the live action movie release in 1994 perhaps this was not so much the case. Nevertheless, Kaneko’s film retains the happy-go-lucky tone and offers note of celebration for the unconventional as a path to success and individual happiness.

Summer Holiday Everyday – It’s certainly an upbeat way to describe unemployment but then everything is improbably upbeat and cheerful in the always sunny world of Shusuke Kaneko’s adaptation of Yumiko Oshima’s shoujo manga. Published in the mid-bubble era of 1988, Oshima’s world is one in which anything is possible but by the time of the live action movie release in 1994 perhaps this was not so much the case. Nevertheless, Kaneko’s film retains the happy-go-lucky tone and offers note of celebration for the unconventional as a path to success and individual happiness. After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy. Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.

Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.