Even when you’re the empress, a woman has little freedom. Teinosuke Kinugasa’s Bronze Magician (妖僧, Yoso) is loosely based on a historical scandal concerning Nara-era empress Koken/Shotoku and a Rasputin-like monk, Dokyo, who unlike his counterpart in the film, eventually tried to seize the throne for himself alone only to have his ambitions frustrated by the empress’ death and the fierce resistance of her courtiers. As the title implies, Kinugasa is more interested in Dokyo than he is in the perilous position of Nara-era women even in power, painting his fall from grace as a Buddhist parable about a man who pays a heavy price for succumbing to worldly passions.

As the film opens, Dokyo (Raizo Ichikawa) emerges from a shallow cave amid many other caves after meditating for 10 years during which he reached a higher level of enlightenment and obtained mystic powers. Now he thinks it’s time to continue the teachings of departed mentor Doen and use his abilities to “actively do good and save the masses”. Before that, however, he does some not quite Buddhist things like turning a rat into a living skeleton, and twisting a snake into a tangle. In any case, he begins roaming the land, miraculously healing the sick. While reviving a thief who had been killed by samurai after trying to make off with a bird they shot, Dokyo is spotted by a retainer of the empress who brings news of his miracles back to her closest advisors.

Empress Koken (Yukiko Fuji), in the film at least, was a sickly child and even after ascending the throne has often been ill. She is currently bedridden with a painful respiratory complaint that is giving her servants cause for concern. None of the priests they’ve brought in to pray for her (apparently how you treat serious illness in the Nara era) has been of much use. The empress’ steward Mabito (Tatsuya Ishiguro) orders that Dokyo be found and brought to the palace to see if he can cure Koken, which he does while stressing that he’s helping her not because she’s the empress but in the same way as he would anyone else.

As might be expected, the empress’ prolonged illness has made her a weak leader and left the door open for unscrupulous retainers intent on manipulating her position for themselves. There is intrigue in the court. The prime minister (Tomisaburo Wakayama) is colluding with a young prince to depose Koken and sieze power. Left with little oversight, he’s been embezzling state funds to bolster his position while secretly paying priests to engineer Koken’s illness continue. Dokyo’s arrival is then a huge threat to his plans, not only in Koken’s recovery and a subsequent reactivation of government but because Dokyo, like Koken, is of a compassionate, egalitarian mindset. She genuinely cares that the peasants are suffering under a bad and self-interested government and sees it as her job to do something about it, which is obviously bad news if you’re a venal elite intent on abusing your power to fill your pockets while the nation starves.

As the prime minister puts it, however, the empress and most of her courtiers are mere puppets, “naive children”. At this point in history, power lies in the oligarchical executive who are only advised by the empress and don’t actually have to do what she says. As she is also a woman, they don’t necessarily feel they have to listen to her which is one reason why the prime minister assumes it will be easy to manoeuvre the young prince toward the throne. Koken’s short reign during which she overcame two coups is often used to support the argument against female succession because it can be claimed as a temporary aberration before power passed to the nearest male heir. Nevertheless, Koken tries to rule, even while she falls in love with the conflicted Dokyo. Her right to a romantic future, however, is also something not within her control. Many find the gossip scandalous and use it as an excuse to circumvent her authority, especially after she gives Dokyo an official title which allows them to argue she has been bewitched by him and he is merely manipulating her to gain access to power.

Dokyo, meanwhile, is in the middle of a spiritual crisis. After 10 years of study he as reached a certain level of enlightenment and attained great powers which he intended to use for the good of mankind. He is happy to discover that Koken is also trying to do good in the world but she is, ironically, powerless while the elitist lords “indulge in debauchery”, abusing their power to enrich themselves while the people starve. He begins to fall in love with her but the palace corrupts him. He accepts a gift of a beautiful robe despite his vows of asceticism, and then later gives in to his physical desire for Koken only to plunge himself into suffering in the knowledge that he has broken his commandments. He loses his magic, but chooses to love all the same while rendered powerless to hold back Koken’s illness or to protect her from treachery.

The pair mutually decide they cannot “abandon this happiness”, and Dokyo’s fate is sealed in the acceptance of the extremely ironic gift of golden prayer beads which once belonged to Koken’s father. He is reborn with a new name in the same way as the historical Koken was reborn as Shotoku after surviving insurrection, embracing bodily happiness while attempting to do good but battling an increasing emotional volatility. The lords continue to overrule the empress’ commands, insisting that they are really commands from Dokyo, while Dokyo’s “New Deal” involving a 2 year tax break for impoverished peasants finds support among the young radicals of the court who universally decide that they must stand behind him, protecting the ideal even if they are unable to save the man.

This troubles the elders greatly. Declaring that Dokyo has used “black magic” to bewitch the empress, they determine to eliminate him, but Dokyo never wanted power. “Power is not the final truth” he tells them, “those blindly pursuing status and power only destroy themselves”. Yet Dokyo has also destroyed himself in stepping off the path of righteousness. He damns himself by falling in love, failing to overcome emotion and embracing physical happiness in this life rather than maintaining his Buddhist teachings and doing small acts of good among the poor. Nevertheless, he is perhaps happy, and his shared happiness seems to have started a compassionate revolution among the young who resolve to work together to see that his ideal becomes a reality even in the face of entrenched societal corruption.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

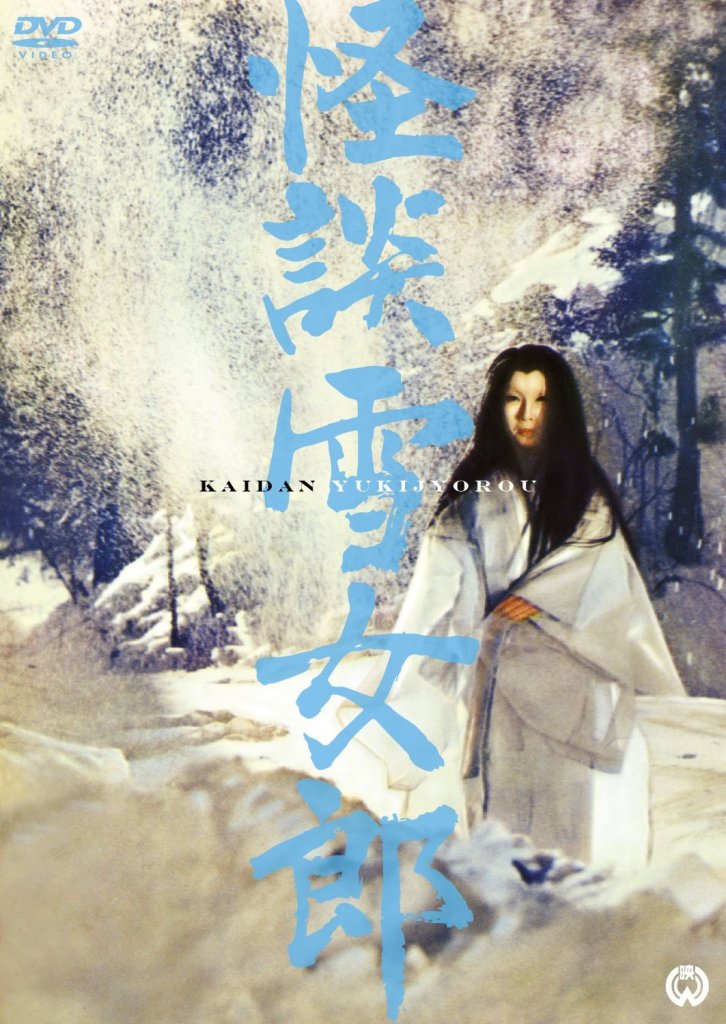

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart. The Snow Woman is one of the most popular figures of Japanese folklore. Though the legend begins as a terrifying tale of an evil spirit casting dominion over the snow lands and freezing to death any men she happens to find intruding on her territory, the tale suddenly changes track and far from celebrating human victory over supernatural malevolence, ultimately forces us to reconsider everything we know and see the Snow Woman as the final victim in her own story. Previously brought the screen by Masaki Kobayashi as part of his

The Snow Woman is one of the most popular figures of Japanese folklore. Though the legend begins as a terrifying tale of an evil spirit casting dominion over the snow lands and freezing to death any men she happens to find intruding on her territory, the tale suddenly changes track and far from celebrating human victory over supernatural malevolence, ultimately forces us to reconsider everything we know and see the Snow Woman as the final victim in her own story. Previously brought the screen by Masaki Kobayashi as part of his  These days, cats may have almost become a cute character cliche in Japanese pop culture, but back in the olden days they weren’t always so well regarded. An often overlooked subset of the classic Japanese horror movie is the ghost cat film in which a demonic, shapeshifting cat spirit takes a beautiful female form to wreak havoc on the weak and venal human race. The most well known example is Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko though the genre runs through everything from ridiculous schlock to high grade art film.

These days, cats may have almost become a cute character cliche in Japanese pop culture, but back in the olden days they weren’t always so well regarded. An often overlooked subset of the classic Japanese horror movie is the ghost cat film in which a demonic, shapeshifting cat spirit takes a beautiful female form to wreak havoc on the weak and venal human race. The most well known example is Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko though the genre runs through everything from ridiculous schlock to high grade art film.

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.

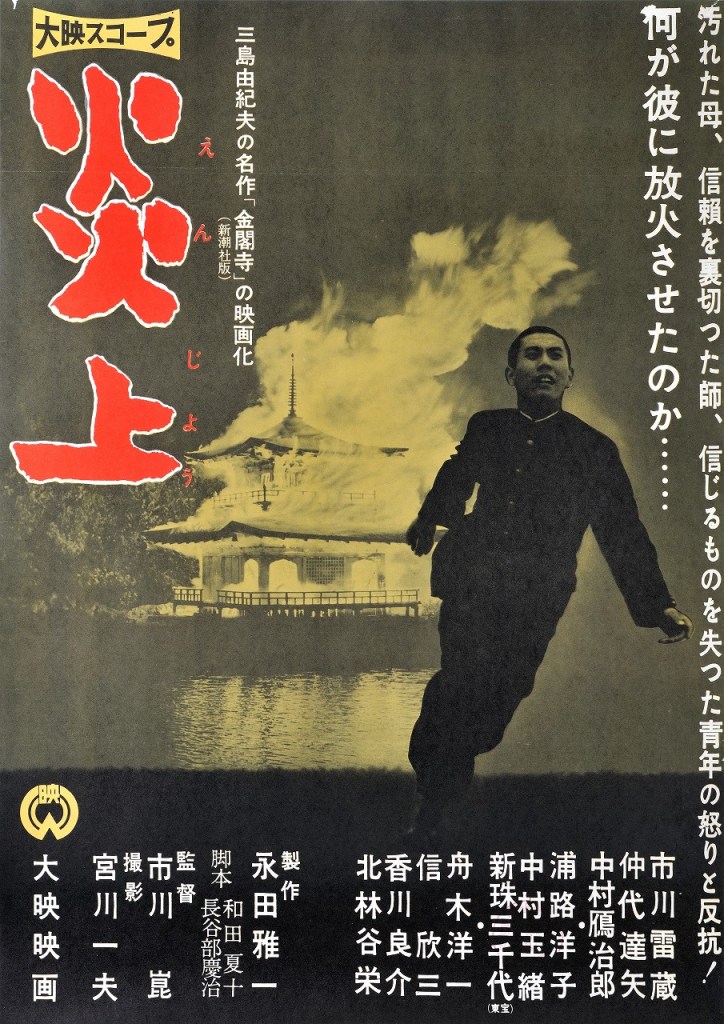

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research. Kon Ichikawa turns his unflinching eyes to the hypocrisy of the post-war world and its tormented youth in adapting one of Yukio Mishima’s most acclaimed works, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Inspired by the real life burning of the Kinkaku-ji temple in 1950 by a “disturbed” monk, Enjo (炎上, AKA Conflagration / Flame of Torment) examines the spiritual and moral disintegration of a young man obsessed with beauty but shunned by society because of a disability.

Kon Ichikawa turns his unflinching eyes to the hypocrisy of the post-war world and its tormented youth in adapting one of Yukio Mishima’s most acclaimed works, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Inspired by the real life burning of the Kinkaku-ji temple in 1950 by a “disturbed” monk, Enjo (炎上, AKA Conflagration / Flame of Torment) examines the spiritual and moral disintegration of a young man obsessed with beauty but shunned by society because of a disability. Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama

Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama