Shojo manga has a lot to answer for when it comes to defining ideas of romance in the minds of its young and female readers. The heroines of Japanese romantic comedies are almost always shojo manga enthusiasts – the lovelorn lady at the centre of Christmas on July 24th Avenue even magics herself into a fantasy Lisbon to better inhabit the cute and innocent world of a manga she loved in childhood. The heroine of Tremble All You Want (勝手にふるえてろ, Katte ni Furuetero), Yoshika (Mayu Matsuoka), does something similar in creating an alternate fantasy world filled with intimate acquaintances each encouraging and invested in her ongoing quest to win the heart of a boy she loved in high school who became the hero of her personal interest only manga, The Natural Born Prince.

Shojo manga has a lot to answer for when it comes to defining ideas of romance in the minds of its young and female readers. The heroines of Japanese romantic comedies are almost always shojo manga enthusiasts – the lovelorn lady at the centre of Christmas on July 24th Avenue even magics herself into a fantasy Lisbon to better inhabit the cute and innocent world of a manga she loved in childhood. The heroine of Tremble All You Want (勝手にふるえてろ, Katte ni Furuetero), Yoshika (Mayu Matsuoka), does something similar in creating an alternate fantasy world filled with intimate acquaintances each encouraging and invested in her ongoing quest to win the heart of a boy she loved in high school who became the hero of her personal interest only manga, The Natural Born Prince.

At 24 Yoshika is still obsessed with “Ichi” (Takumi Kitamura) who is forever number “One” in her affections. Working as an office lady in the accounts department, Yoshika’s fingers tip tap over the calculator all day long until she can finally go home and read about her favourite topic, extinct animals, on the internet before it’s time to head back to work. Because of her undying love for Ichi (whom she has not seen or heard from in many years), Yoshika has never had a boyfriend or engaged in “dating” – something which causes her a small amount of anxiety and embarrassment when considering the additional awkwardness of starting out at such a comparatively late age.

Yoshika’s dilemma reaches a crisis point when, much to her surprise, a colleague becomes interested in her. Kirishima (Daichi Watanabe), whom she rechristens number “Two”, is, like her, slightly shy and bumbling but also outgoing and with a need to say things out loud. Seeing as this is apparently the first time this has ever happened to Yoshika, she finds it very confusing – not least because she can’t decide if “dating” Kirishima is a betrayal of Ichi or if she is really ready to leave her Natural Born Prince behind.

The dilemma isn’t so much between man one and man two but between fantasy and reality, idealism and practicality. Yoshika, painfully shy, lives in a fantasy world of her own creation as we discover during a tentative, emotionally raw musical number in which she is forced to confront the fact that the reason she doesn’t know the names of any of the people we’ve seen her repeatedly engage with is that, despite her longing and her loneliness, she has never been able to pluck up the courage to actually speak to them. Thus they exist in her head as a series of nicknames, theoretical constructs of “friends” with whom to engage in (one-sided) conversations – a frighteningly relatable (if extreme) concept to the painfully shy. Deprived of her fluffy fantasy, Yoshika arrives home to collapse in tears and finds her world growing colder, riding the bus all alone and eventually cocooning herself in her apartment.

Thus when Kirishima starts to show an interest, Yoshika can’t quite figure out which “reality” she is really in. The idea that he might simply like her doesn’t compute so she assumes the worst and pushes him away in grand style, retreating to the entirely safe world of Ichi worship in which she, in a sense, has already been rejected so there is nothing left to fear. Coming up with a nefarious plan to meet Ichi by stealing the identity of a former classmate and organising a reunion, Yoshika’s fantasy is challenged by the man himself or more specifically his perception of events which differs slightly from her own owing to not placing herself at the centre. Though Yoshika had correctly surmised that Ichi was uncomfortable with the attention he received as the school’s “number one” and decided to ignore him as a token of her love, she remained unaware of the degree to which he suffered in her obsession with her own unrequited desires.

Wondering if she should just “go extinct” like the animals she loves so much who evolved in ways incompatible with life on Earth – literally too weird to live, Yoshika begins to lose her grip on the divisions between fantasy and reality, unable to accept the “real” attention and affection of those who would be her real world friends if she’d only let them while continuing to engage in the wilfully self destructive mourning of her illusions. Tremble All You Want (but do it anyway) seems to become Yoshika’s new mantra as she makes her first active decision to gravitate towards the land of the real despite her fear and the conviction that it will not accept her. Filled with whimsical charm but laced with a particular kind of melancholy darkness, Ohku’s tale of modern love in a disconnected world is a strangely cheerful affair even as our heroine prepares to swap her colourful fantasy for the potential comforts of the everyday.

Screened at the 20th Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (hit the subtitle button to turn on English subs)

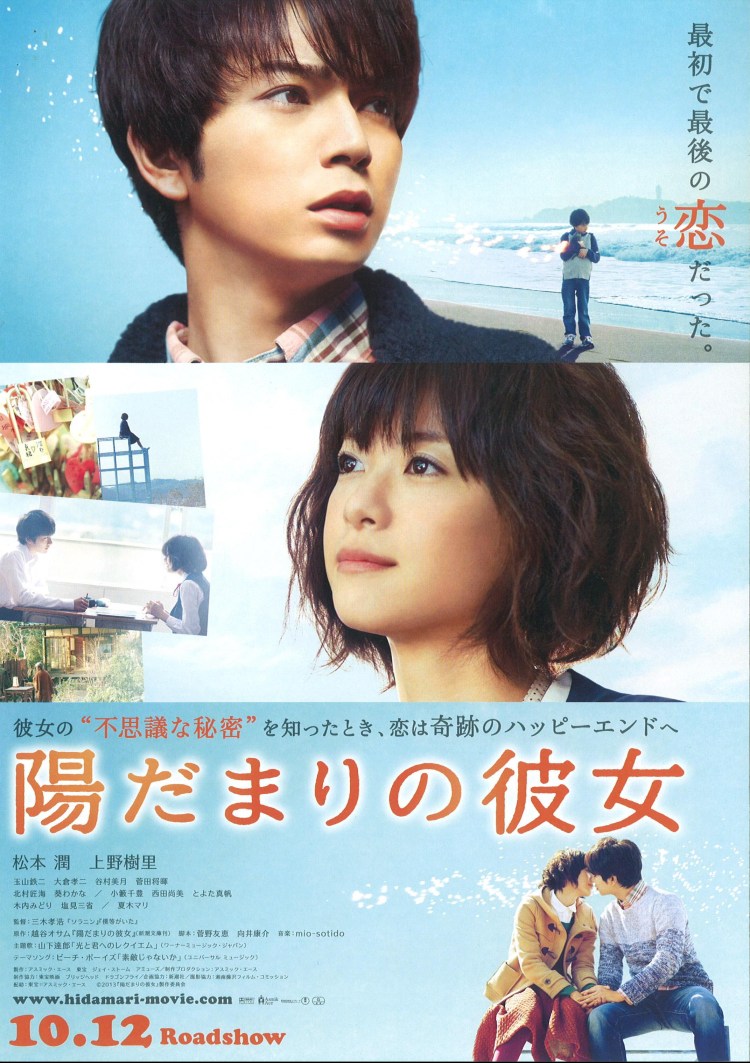

The “jun-ai” boom might have been well and truly over by the time Takahiro Miki’s Girl in the Sunny Place (陽だまりの彼女, Hidamari no Kanojo) hit the screen, but tales of true love doomed are unlikely to go out of fashion any time soon. Based on a novel by Osamu Koshigaya, Girl in the Sunny Place is another genial romance in which teenage friends are separated, find each other again, become happy and then have that happiness threatened, but it’s also one that hinges on a strange magical realism born of the affinity between humans and cats.

The “jun-ai” boom might have been well and truly over by the time Takahiro Miki’s Girl in the Sunny Place (陽だまりの彼女, Hidamari no Kanojo) hit the screen, but tales of true love doomed are unlikely to go out of fashion any time soon. Based on a novel by Osamu Koshigaya, Girl in the Sunny Place is another genial romance in which teenage friends are separated, find each other again, become happy and then have that happiness threatened, but it’s also one that hinges on a strange magical realism born of the affinity between humans and cats.

Somewhere near the beginning of Daishi Matsunaga’s debut feature, Pieta in the Toilet (トイレのピエタ, Toire no Pieta), the high rise window washing hero is attempting to school a nervous newbie by “reassuring” him that the worst thing that could happen up here is that you could die. This early attempt at black humour signals Hiroshi’s already aloof and standoffish nature but his fateful remark comes back to haunt him after he is diagnosed with an aggressive and debilitating condition of his own. Noticeably restrained in contrast with the often melodramatic approach of similarly themed mainstream pictures, Pieta in the Toilet is less a contemplation of death than of life, its purpose and its possibilities.

Somewhere near the beginning of Daishi Matsunaga’s debut feature, Pieta in the Toilet (トイレのピエタ, Toire no Pieta), the high rise window washing hero is attempting to school a nervous newbie by “reassuring” him that the worst thing that could happen up here is that you could die. This early attempt at black humour signals Hiroshi’s already aloof and standoffish nature but his fateful remark comes back to haunt him after he is diagnosed with an aggressive and debilitating condition of his own. Noticeably restrained in contrast with the often melodramatic approach of similarly themed mainstream pictures, Pieta in the Toilet is less a contemplation of death than of life, its purpose and its possibilities. Koji Fukada first ventured into the family drama arena with the darkly comic satire

Koji Fukada first ventured into the family drama arena with the darkly comic satire  “What would John do?” is a question Cassavetes loving indie filmmaker Tetsuo (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) often asks himself, lovingly taking the framed late career photo of the godfather of independent filmmaking in America down from the wall. Unfortunately, if Cassavetes has any advice to offer Tetsuo, Tetsuo is not really paying attention. An example of the lowlife scum who appear to have taken over the Japanese indie movie scene, Tetsuo hasn’t made anything approaching art since an early short success some years ago and mainly earns his living through teaching “acting classes” for young, desperate, and this is the key – gullible, people hoping to break into the industry.

“What would John do?” is a question Cassavetes loving indie filmmaker Tetsuo (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) often asks himself, lovingly taking the framed late career photo of the godfather of independent filmmaking in America down from the wall. Unfortunately, if Cassavetes has any advice to offer Tetsuo, Tetsuo is not really paying attention. An example of the lowlife scum who appear to have taken over the Japanese indie movie scene, Tetsuo hasn’t made anything approaching art since an early short success some years ago and mainly earns his living through teaching “acting classes” for young, desperate, and this is the key – gullible, people hoping to break into the industry. From the Ozu-esque, classic calligraphy of its elegant title sequence, you might expecting a rather different kind of family drama than the one you find in Koji Fukada’s Hospitalité (歓待, Kantai). Though his compositions lean more towards the conventional, Fukada aims somewhere between a more restrained

From the Ozu-esque, classic calligraphy of its elegant title sequence, you might expecting a rather different kind of family drama than the one you find in Koji Fukada’s Hospitalité (歓待, Kantai). Though his compositions lean more towards the conventional, Fukada aims somewhere between a more restrained